3 takeaways for travelers from Boeing's month of reckoning

October marks a year since the first crash of Boeing’s 737 MAX jet, which killed all passengers aboard.

Boeing's board and management are trying to show that they are controlling the crisis touched off by the crashes, the worldwide grounding of the planes, and the constant drip, drip, drip of revelations.

Behind those revelations: the flight control system believed to have defeated the pilots and crashed the planes.

Here’s what travelers should know, whether they care a lot or a little about what kind of a plane they fly in.

The survivor and the fall guy

Kevin McAllister is the fall guy. He was recruited to head Boeing’s Commercial Airplanes division in 2016. His picture and biography were stricken from Boeing's website overnight.

Sponsored

McAllister was not at Boeing when the 737 MAX was in key design stages. But he is being held responsible for what has happened since, including how he’s handled aggrieved 737 airline customers and troubles with other planes including Boeing’s lagging 777X program.

This is a move to show the world that someone has paid the price for the crashes, and that there will be new leadership. Stan Deal, a longtime Boeing insider, is the new head of the division.

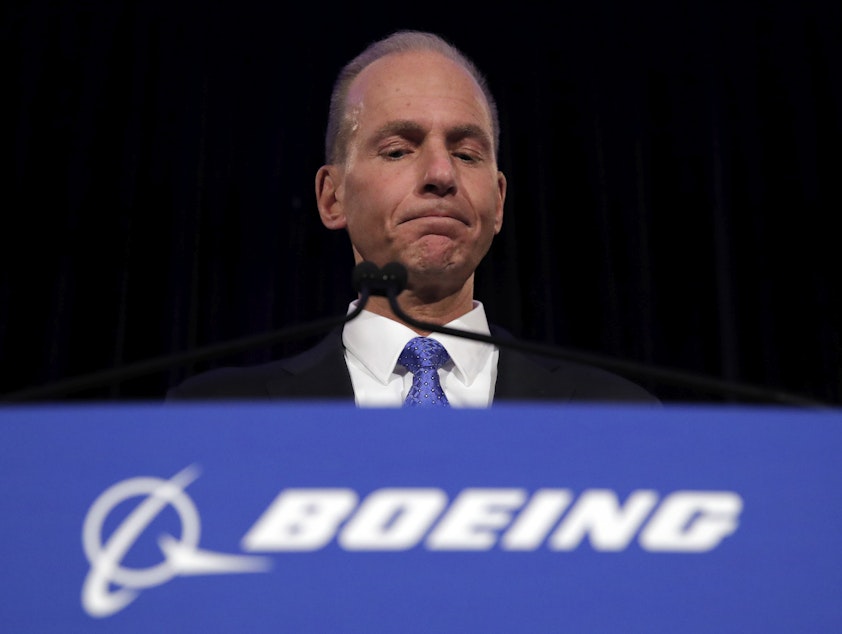

The survivor is Dennis Muilenburg, chief executive of Boeing. Despite wooden apologies to victims, Muilenburg’s penance is to see the MAX through to re-certification by the Federal Aviation Administration and other world flight authorities.

Muilenburg is not unscathed. He's lost leadership of the board of directors, which oversees Boeing. That board will now oversee his management — meaning he may not be out of the woods yet.

The pressure is on, and it's coming from the flying public.

Sponsored

Many airlines cannot meet passenger demand because they counted on being able to fly MAXs. Some routes have been cut back or cancelled because of the grounding. Others have failed to expand to meet accelerating demand.

Facing the crisis of trust

Boeing must regain and keep public trust in order to ensure the success of its best-selling plane when it does return to service.

October marked a low point for trust in Boeing when instant messages surfaced that appeared to indicate a Boeing pilot discovered troubles with the flight system, known as MCAS, back in 2016. The company’s stock took a pummeling. And even when Boeing offered an explanation – that the pilot had discovered problems with the simulator not the MCAS software – the stock didn't recover.

On Wednesday's earnings call, Muilenburg said Boeing’s fix for the flight system will contain multiple layers of redundancy — even for the most obscure possibilities that didn't surface in the crashes.

Sponsored

He also addressed cultural change, saying the role of the engineer would be elevated and that the chief engineer would report directly to him. That’s important for Boeing internally.

Engineers have been saying for years that the company’s drive to produce new planes was making it more and more difficult to speak up over issues that could affect safety.

Boeing’s month of reckoning continues

Next week Muilenburg testifies before Congress, where more questions about what Boeing knew and when it knew it are bound to surface. A federal criminal investigation continues, as does a federal probe of Boeing's own role in the FAA’s certification of the 737 MAX.