PHOTOS: An altar for Seattle's immigrant workers

Dia de los Muertos brings single, mostly male workers together at Casa Latina. Together they build an altar to remember and celebrate their friends and co-workers who died alone in the U.S.

Twelve portraits hang on a glowing altar inside of Casa Latina in Seattle’s Central District.

Gabriel Aguilar.

Salvador Gonzalez.

Jose Figueroa.

These are the names of the dead. The living bring them back every year with candles, painted calaveritas, and the heady scent of marigolds.

Sponsored

Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) has moved into the mainstream thanks to Pixar’s Coco and a growing number of events that invite people of all backgrounds to celebrate.

But this particular altar isn't fairy tale with a happy ending; many of the men on the altar died alone in the U.S. without their families. Some were deported and passed away in their native countries.

Francisco Jose Trujillo shows up Casa Latina’s Day Worker Center at 6 a.m. every morning. If he’s lucky, he can get a construction gig and even save for when work becomes sparse in the winter.

Sponsored

Trujillo hasn’t set up an altar in years. “It’s not the same here,” he says in Spanish.

Back in Oaxaca, Mexico, he went to the cemetery with his mom to clean their family’s tombs and set up food and candles.

His family still lives in Mexico — including two adult children he hasn’t seen in well over 10 years. Trujillo plans to work a couple more years and then head back.

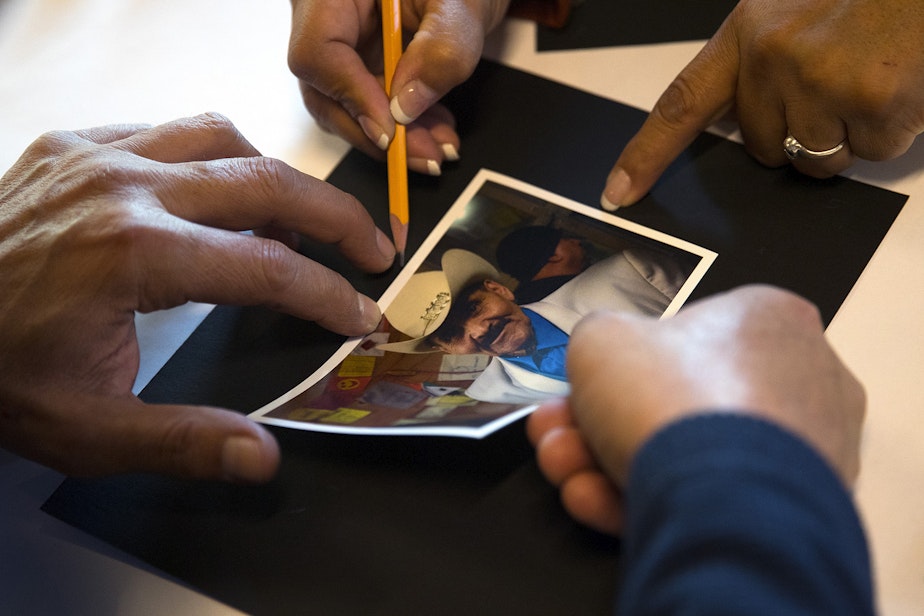

Today he doesn’t join in the altar building but he does point out the names of the deceased men he used to work with.

Sponsored

One of them, an older gentleman named Miguel Adame looks dapper with a cowboy hat, sharp suit, and a mustache. Trujillo says Adame was a good dancer — light on his feet and always at all the bailes (dances).

Sergio Ochoa, another of the living, points to a photo of his friend Hugo Garcia, who died last year. He was deported from the U.S. in December and died shortly after.

Ochoa doesn’t say much when I ask if he misses him. Instead he jokes he would place a beer as on offering on his grave if he could.

“The living here would take it though! It wouldn’t last an hour,” he says laughing.

Sponsored

Watching the workers with glitter and paintbrushes, there’s a strange undercurrent in the air. Perhaps it’s the contrast of seeing them in their steel toe boots and Carharts, trying to get a ribbon just right.

The feeling is quietly joyous, a kind of happiness in remembering the men's youth and participating in this ritual in a country that’s not quite their own.

The men know they will end up on someone’s altar some day. But today they paint another sugar skull with bright reds and yellows. They tell stories about their dead. And when they’re called, they head back to work.