As Travis Decker manhunt stalls, Wenatchee veterans call for more mental health services

A 32-year-old military veteran, Travis Decker, is wanted for allegedly killing his three young daughters outside of Wenatchee in central Washington last month. Since their deaths, people close to him have raised questions about whether he had adequate mental health care for his diagnosed borderline personality disorder, and for what some speculate could also have been PTSD.

Now, the veteran community in north-central Washington is asking for increased mental health services — to help prevent the next tragedy.

When TJ Decker, himself in the military, moved with his family from their station abroad to Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Pierce County, he was excited to be just a few hours from his brother Travis.

“We talked about, ‘We’re going to go camping, we’re going to do holidays together,’” TJ Decker said. “I have two kids with autism, and [Travis’] girls absolutely wrapped them up and showed them so much love. They were so good with them.”

“That was the plan,” Decker added, “and then he wanted nothing to do with us.”

RELATED: Is Travis Decker still alive? WA search continues for man suspected of killing his 3 daughters

TJ Decker said his brother’s mental health deteriorated after he left the active reserves in 2021.

“He was struggling with transitioning out of the military — trying to find work, trying to find his new role,” TJ Decker said. “It’s not just your day; this is my identity as well. When you get out of the military and take off that uniform, you lose your identity.”

“Before that, … we were bullshitting, talking on the phone all the time,” he said. “Everything seemed fine.”

But then, his brother stopped taking his calls.

TJ Decker and his dad went to see Travis Decker in Wenatchee, to see if they could help him get back on track.

“We just tried to show up and talk to him and see what’s going on, what do you need,” TJ Decker said. “Obviously, it didn’t work. Everything fell on deaf ears.”

Travis Decker’s current whereabouts remain unknown, despite an ongoing manhunt. His three daughters, ages 5, 8, and 9, were found suffocated to death near a campsite in Chelan County on June 2, after he’d failed to bring them home from a scheduled visit.

Whitney Decker, Travis Decker’s ex-wife, declined an interview, but KUOW spoke with her lawyer Arianna Cozart, who’s worked with the family for the past year.

After leaving the military, Travis “suddenly felt very alone and was still facing a lot of ramifications of his combat that he saw: nightmares, insomnia, severe insomnia at times,” Cozart said.

RELATED: Trump's policies are destabilizing mental health care for veterans, sources say

He had trouble keeping things together and became homeless. He was living in a camper van, and at the National Guard armory in Wenatchee. Cozart said he sometimes showed bad judgment — like taking the girls camping in Montana without telling their mom.

Because of that, and because he had no stable housing, Whitney Decker took him back to court to ask that he not be allowed to have the girls overnight. The court agreed — and after that, things started to get better, according to Cozart.

In the months leading up to the alleged murders, Travis Decker was the best co-parent he’d ever been, Cozart said.

“He’s shown up to every dance class,” Cozart said. “He’s shown up to every game, every practice. He’s really been showing up and engaged. I mean, very communicative — like, ‘Hey, we’re going to be five minutes late.’ Or, ‘Hey, we’re at the ice cream shop; we’ll be there in 10 minutes. Is that OK?’”

Travis Decker had never been violent toward Whitney or their children, Cozart said.

“Those girls loved their time with their dad,” Cozart said. “He loved those girls. He really did. She never thought he would hurt those girls.”

Cozart said Travis Decker was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder as he was leaving the military, but she thinks he likely also had PTSD. The judge in the custody case ordered him to get a psychiatric evaluation, an anger management evaluation, and twice-monthly therapy. Court records state factors of neglect, and physical and emotional problems as the reasons.

“Travis did contact me after the hearing and say, ‘How do I get these evaluations? What do I need to do?’” Cozart said. “And I directed him to the VA, because I thought that they would help him. I know that he called the VA and said that he needed to get a psychiatric evaluation, and that they told him they couldn’t do that. I know that that is incorrect — that they do them all the time, including locally.”

Cozart said Decker did not get the ongoing therapy he was supposed to, though he did call the veterans crisis hotline at least once — but that’s just for crises, not for followup or regular therapy.

“If we would have [had] the resources that Travis deserved, earned, needed, that could have saved these girls,” Cozart said. “This really could have been prevented. It really could have, and that is part of what is so devastating.”

KUOW reached out to the VA regarding Travis Decker’s access to mental health care but they did not respond.

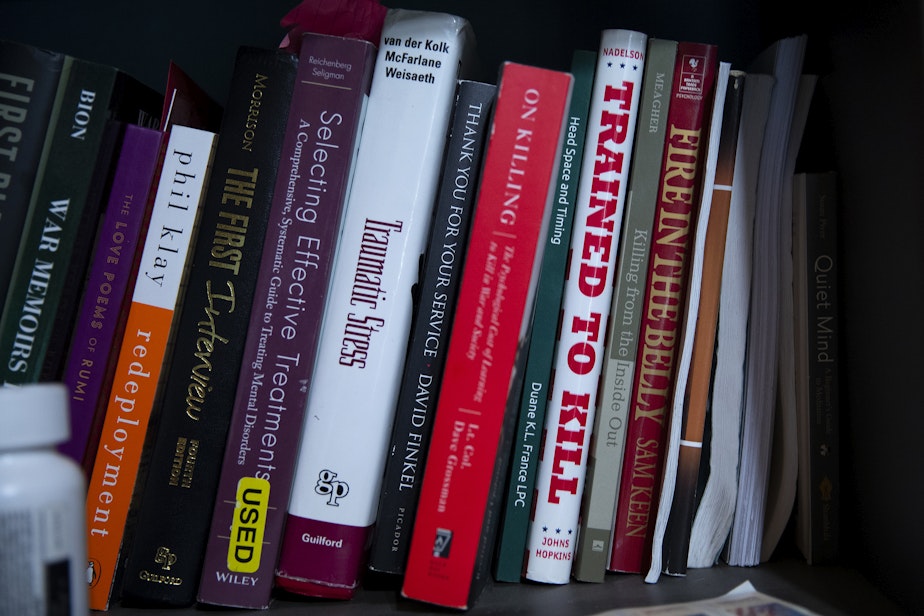

Just a couple of weeks before his daughters’ death, Travis Decker walked out of the Grant County Veterans Services office — and Rob Bates, a mental health counselor for veterans, saw him. Later, when Decker’s photo was on the news, Bates realized who he’d seen.

“So he was trying to engage services,” Bates said. “We just didn't have the services that he needed. I think most of what I have is anger at the system, because the system failed him. We — we failed him. We failed Whitney, and mostly we failed those children.”

Bates said it’s hard for veterans to find mental health care in north-central Washington.

Bates himself was in the Army for 20 years, including a total of five years in combat — in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“Our last deployment to Afghanistan, we — I can't even tell you how many people died,” Bates said. “I used to not be able to close my eyes and not see … an IED that went off in Mosul that was so close it literally knocked me out.”

“It's one of those moments where time stops and you can see everything in the air,” Bates added.

When Bates retired from the military in 2011, he was suffering from PTSD, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation.

He was able to get the help he needed — because, he said, he was living in Olympia at the time, and on the west side, “you can’t throw a rock without hitting services for veterans.”

Bates said the trauma he suffered is still there, but now he has the coping skills to manage it and continue to function, and he’s able to recognize warning signs and triggers.

Bates became a counselor because he wanted to help other veterans as they recover from trauma, and leave the structure and identity provided by military service. These days, he sees about 30 veterans a week.

“I wish I had more capacity so I could [help] more people,” Bates said. “If we don't do that, we're going to continue to see acts of violence. We're going to continue to see substance use disorders. We're going to continue to see veteran homelessness. You know, we're going to continue to see veterans struggle just to do the basic things.”

Bates said there’s a high concentration of vets in the Wenatchee Valley — and many of them have mental health needs and came here to get away from the stressors and triggers of big-city life. But there are only a handful of counselors with the cultural competency to serve veterans; he estimates that the valley needs at least 20 counselors for veterans to meet the demand.

And Bates and other advocates say federal and state funding cuts are imperiling even those services that do exist. The VA’s contract with Central Washington Veterans Counseling, which serves 160 veterans on an ongoing basis, sunsetted at the end of June; and the counseling center’s state funding is also at risk.

KUOW reached out to the VA about the availability of mental health services in the Wenatchee Valley but they did not respond.

In the weeks before he allegedly killed his daughters, Travis Decker was spotted outside of a gathering place for veterans in downtown Wenatchee called the Bunker.

The Bunker’s founders hoped it would be a safe space where veterans can just hang out, and also share resources and strategies to get help.

Over the course of one weekday morning, KUOW spoke with several veterans as they drifted in and out.

Many of them said the news of what Travis Decker did hit them hard, and they’re grateful for a place like the Bunker, where they can process it with fellow vets.

“I use this as therapy, usually,” said Ken Murtagh, who was in the Air Force in the Vietnam War. “And if I didn't have these guys, you know, it'd be tough, because it's nicer to share things with people that have walked in your shoes, you know? I mean, I can tell these guys anything, and they understand.”

“The Bunker is my therapy” was a common sentiment among the regulars. But most said they’re in actual therapy as well, and some are on medications too. The Bunker is an important space, they said — but they still need counselors.