Asian American history isn't required in WA schools. A new group wants to change that

O

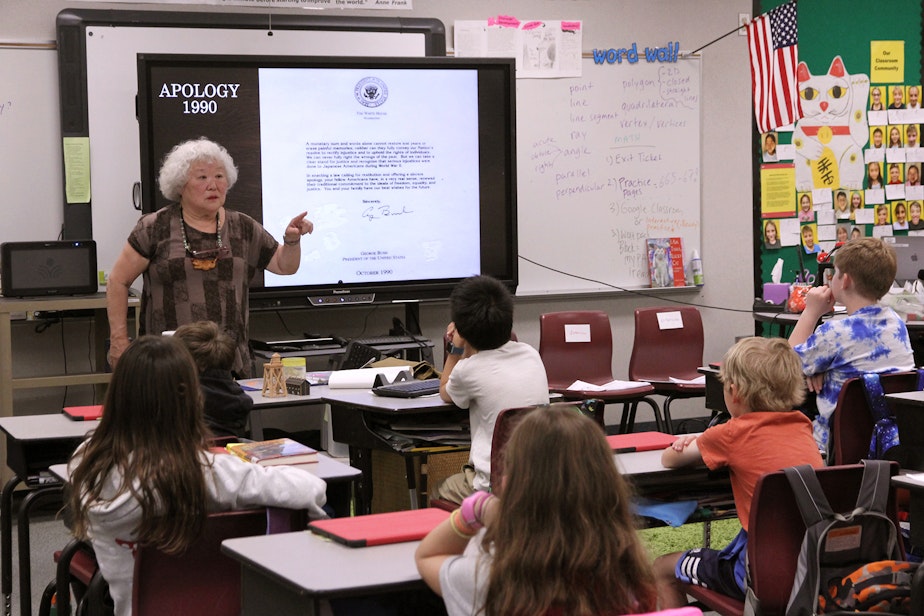

n a recent Friday afternoon at West Mercer Elementary, a fourth grade class sits riveted at their desks.

They’re wide-eyed as a special visitor speaks.

“I was born when my parents were in a prison camp on the Puyallup Fairgrounds,” Judy Kusakabe tells them.

She was born in 1942 — a few months after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. In response, the U.S. government forcibly removed Japanese Americans from their homes and into internment camps.

Sponsored

Among the 120,000 people impacted by the order were Kusakabe’s parents in Seattle. And like many of them, her parents were American citizens.

“We lost our lives that we developed in America. We had to spend years in a place that was so challenging,” Kusakabe said. “And then when we came back, we had to start all over.”

“This was whole families — parents, grandparents, men, women, children, even babies,” she continued. “And our only crime was that we were Japanese.”

It’s considered one of the most barbaric civil rights violations in U.S. history. And yet, Kusakabe — and many students after her — didn’t learn much about it in school.

That’s why the 80-year-old Mercer Island resident has spent the last two decades traveling to dozens of classrooms across the state, sharing her family and friends’ stories with upwards of 1,000 students every year.

Sponsored

She’s got a way of making the history come alive for kids.

“So, how would you feel if you were blamed for something you didn’t do, you were punished for it, and you didn’t have a chance to defend yourself,” Kusakabe asked Denise DiPrima’s fourth grade class during a recent presentation.

“I would be confused, like why?” one student said.

“Yeah,” Kusakabe responded, nodding, “like why are you picking on me?”

“I would feel really upset and angry at the people who got us in trouble for nothing,” another child said.

Sponsored

“Yeah, and it’s something you had nothing to do with,” Kusakabe said.

Kusakabe is part of a growing national movement called “Make Us Visible.” The bipartisan coalition is advocating for Asian American and Pacific Islander history to be mandatory in K-12 curriculum.

Since it started in 2021, 13 states — including Washington — have launched Make Us Visible chapters. So far, three states have passed legislation to require this curriculum.

“It’s so important to feel that sense of belonging and to be seen,” said Angelie Chong, director of Washington’s Make Us Visible chapter. “And it has a huge impact on students’ learning and interest in school.”

Sponsored

The Asian American community in Seattle has deep roots, going back generations. Chong was surprised when she started hearing that many in her community have experienced more racism when Covid broke out.

That is, until it happened to Chong and her two sons.

One day in 2020, they were walking across the street when a car slowed down next to them.

“A woman rolled down her window, shouted at us … and pulled her eyes slanted and stuck her tongue out at us, then drove away,” Chong recalled. “I think this woman just saw us the way most of the country at the time saw us.”

“We were portrayed as people who were foreign; people who were bringing in diseases,” she added. “I remember feeling helpless that we were here again.”

Sponsored

In Washington, hate crimes against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are the highest they've been in 20 years, according to a new report from the Anti-Defamation League of the Pacific Northwest.

While Chong said Washington schools offer more ethnic studies classes than most others across the nation, she thinks the state can do better than elective courses.

“I think when we’re missing in history, that perpetuates the notion that we are not part of this country,” Chong said. “And that has to change, because we are very much part of the fabric of this country and the shaping of the U.S.”

Brett Han, a student member of Make Us Visible Washington, agrees. A 17-year-old senior and second generation Korean American, Han is one of few Asian American students at Seattle Academy.

Han said she often felt like she didn’t belong and didn’t see her identity represented in history classes at the private school.

But during the pandemic, Han watched "Asian Americans," a five-hour PBS series about the role Asian Americans played in shaping U.S. history. She said the series made her realize how much her classes had left out.

“After watching that, I was like, ‘I should be learning about this in school,'” Han said. "If I could’ve learned about my AAPI predecessors at a younger age, I think it would’ve first empowered me but also reassured me that I’m equals with my classmates. I’m not foreign. I’m an American, just like you.”

So, Han reached out to her school’s history department chair and helped him build a new Asian American history class.

She got to take the class this fall. But she wishes all students — at her school and others across Washington — learned about it.

Make Us Visible Washington plans to push lawmakers next year to make that happen.