Blooming in Seattle: Mayor Harrell’s family history of change, challenge, and flowers

Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell’s favorite flower is a red classic rose.

“As my mother used to tell me, if you are going on a date you can’t go wrong. And of course, that’s my mother’s name,” Harrell said.

The rose was also the favorite flower of Harrell's grandfather, John Kobota, who ran a Seattle flower shop called Cherry Land Florist in the 1930s. The shop was on 12th Avenue and Yesler Way, at the edge of the Chinatown-International District. It nearly covered the entire block. Before World War II, this neighborhood was known as Japantown, or Nihonmachi. Today, it looks very different.

“You know, cities change; they evolve,” Harrell said with a slightly somber expression. “There’s a nostalgic pull. There’s some sadness involved. But I have to recognize that cities don’t stay the same. They can’t stay the same.”

RELATED: How a young Black family fought John L. Scott and changed Seattle

Seattle is an ever-changing city, facing one challenge after the other. Harrell knows this well, personally and professionally. He has helped shape the city for more than a decade, first as a City Council member (2008-2020), which included four years as Council president, then as mayor, coming into office in 2022.

For Harrell, Seattle’s story is also a family story. His family survived wartime incarceration based on ethnicity; racism; family division and reconciliation. Harrell often remembers all of it through the lens of that long-gone Seattle flower shop. That’s where, despite harsh realities, love and optimism blossomed, largely because of his Japanese American mother, Rose.

Sponsored

The young Harrell would help his mom cut flowers at the shop, but he admits he wasn’t very good at it. He was more interested in reading comic books — Superman and Spider-Man.

“Those were some good times,” he recalled.

When the shop started in the 1930s, it was “very prolific,” Harrell said. Cherry Land supplied flowers to major hotels and funeral homes throughout the Seattle area. They had a reputation for being customer friendly. Cherry Land became a hub for the Japanese American community, and grandfather Kobata became a local leader. That was before WWII.

After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the United States entered the war. Panic and anti-Japanese rhetoric spread across the country. The FBI began arresting Japanese immigrants, many of whom were religious or business leaders. One such leader was Kobata, who was arrested for treason.

Sponsored

“I’m sure the government had their eye on him because he was quite the entrepreneur,” Harrell said. “They thought, maybe, he had some other activities going on, which were baseless.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, forcing the removal of Japanese Americans from West Coast communities. They were rounded up and sent to incarceration camps.

Harrell’s grandmother, Rose, was 9 years old at the time. Her older siblings shielded her from reality.

“She thought they were literally going to camp, like a good camp,” Harrell said.

Then Rose saw her older brothers and father cry. “She realized, when she saw the tears, that this wasn’t a fun camp. There’s something really serious going on,” he said.

Sponsored

RELATED: Japanese American survivors revisit a troubling past and vow to protect the Idaho prison camp where they were held

Rose’s family shared the same fate as about 125,000 Japanese American citizens, two-thirds of whom were American born, for the crime of being ethnically Japanese. Rose, her family, and many others were sent to the Puyallup Assembly Center, aka “Camp Harmony” (located at the Washington State Fair Grounds).

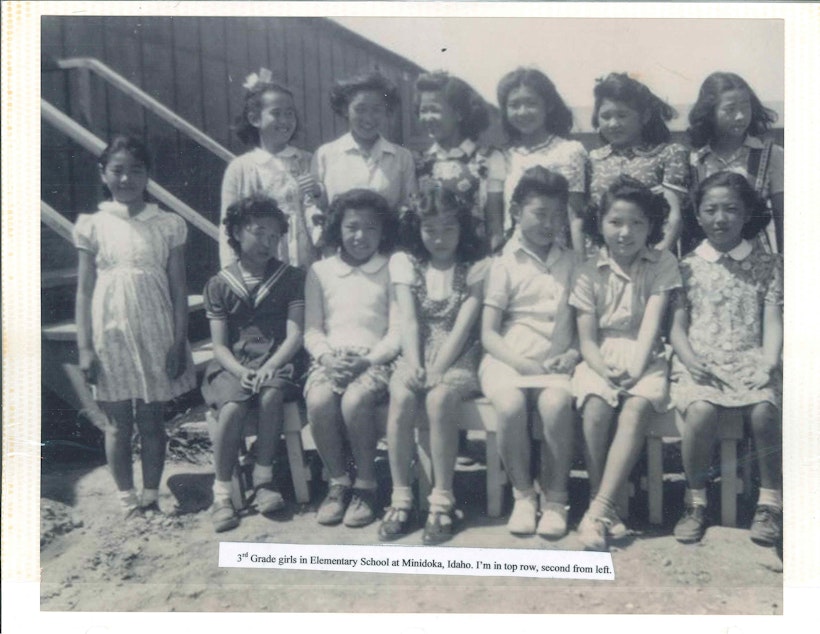

They were then transferred to the Minidoka camp in Idaho, surrounded by barbed wire. The site was a desert, known for brutally hot summers and bone-chilling winters. Storms left up to an inch of sand piled up on the floor of their barracks.

When telling her son about the experience, Rose didn’t describe it in harsh terms. She mostly talked about being with her siblings.

Sponsored

“She perhaps didn't realize she couldn’t leave,” Harrell said.

From the perspective of a child, living in close quarters with their siblings might be “sort of fun.”

Harrell has since heard other heartfelt stories from other Japanese American community members.

“If I’m going to be brutally honest, they were trying to convince themselves of the good things of camp,” Harrell said, describing his mother as an “eternal optimist,” adding it wasn’t her “personality to dwell on anger.”

Today, he wonders if this was his mom’s way of dealing with trauma.

Sponsored

Restarting life in Seattle

Rose and her family returned to the Seattle area after the war. She was excited to start public school, attending Bailey Gatzert Elementary School, then Garfield High School.

“I think she probably blocked out any negativity,” Harrell said. “She was happy to be free. She’s now walking the halls as a young student, hoping to make something of her life.”

Japanese American families lost much of what they owned during the war — homes, land, and businesses. Rose’s family lost most of their possessions, too.

Despite Rose’s “eternal optimism,” she had a hard time reconciling the anger she saw in her siblings, who were much older. They "truly felt the brunt" of seeing and living through WWII as a Japanese American. When her family returned from camp, “it was traumatic.”

“It was just helter-skelter. Where do I go? Where do I sleep?" Harrell said. "My mother talked about that in a less than pleasant way.”

Harrell’s family was able to get back a fraction of the property where Cherry Land Florist once stood. They re-established the flower shop, and named it Cherry Land Florist II. It didn’t take long for the business to thrive once again.

Growing up biracial

In 1953, Rose, a Japanese American woman, married Clayton Harrell, an African American man.

“It was a different time,” Harrell said, reflecting on the strain his parents’ marriage put on his family.

Rose stayed close with her younger sister, Louise, who was closer in age. Clayton’s African American family accepted Rose.

“They all love my mother,” Harrell said, adding that his mom learned how to cook red beans, rice, corn bread, and “all that good southern food.”

Harrell was born in 1958. He grew up during the era of race riots and the civil rights revolution.

“For a young biracial kid, it was confusing because a lot of people look badly and poorly upon someone who's biracial,” Harrell said. “You're not in this group. You're not in that group. And sometimes kids, you know, [they’d] bully me. Bullying is not new.”

Harrell recalled playing basketball with his friend Frank when he was 13 years old. A group of older boys took their ball and “kicks.” They called him names that referenced his mixed heritage. Harrell declined to repeat the names.

“I’m going to be a better ball-player than everyone in there,” Harrell told Frank after the incident. “I’m going to teach them to never take my ball again.”

Harrell walked away, crying and angry. “I remember it like it was yesterday.”

The fact they were a biracial family was not lost on Harrell’s parents. They openly spoke about it with their children.

“You’re going to be called names you’ve never been called before. People are not as nice as you want them to be,” they told their son before starting ninth grade. “Are you up for it?”

From the young Harrell’s perspective, it wasn’t anything he hadn’t already gone through.

“I don’t like bullies, because I experienced bullies growing up,” Harrell said. “But it made me stronger. I think it made me kinder as well.”

RELATED: Can the 'ghost corner stores' of Seattle's past rise from the dead?

Harrell had a strong network of friends who loved and supported him in the AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander) and Black community, so he was able to let the name-calling “bounce off” of him.

Overtime, Rose’s extended family began to come around. Harrell attended the University of Washington and played football for the Huskies. Rose’s siblings saw their nephew “do a few positive things,” Harrell said. That prompted them to catch up, and mend fences.

RELATED: 'I wonder if people think you took that baby.' Navigating Seattle as a biracial family

Growing up in Cherry Land

Walking along 12th Avenue and Yesler, Harrell remembers spending his weekends at the corner, helping his mother at Cherry Land Florist.

Harrell often watched Rose cut flowers — he called it artwork. Then he would pay homage, and try to cut some flowers. But he took a freestyle approach to it.

“[I would] just cut randomly and wildly," he said. "It was a lot of fun.”

He’d get kicked out and sent to run errands, get ice cream cones, or visit family at nearby businesses.

“And I would just go back and read comic books with my cousins,” he said.

Today, Cherry Land is gone. It was sold and closed in the early 1980s. A high-rise apartment building stands in its place, looking over bustling vehicles as the chiming street car stops for passengers.

Standing on the corner, Harrell says it’s important to tell family stories as Seattle evolves, to keep photos, and to celebrate history.

“That’s how you move forward.”