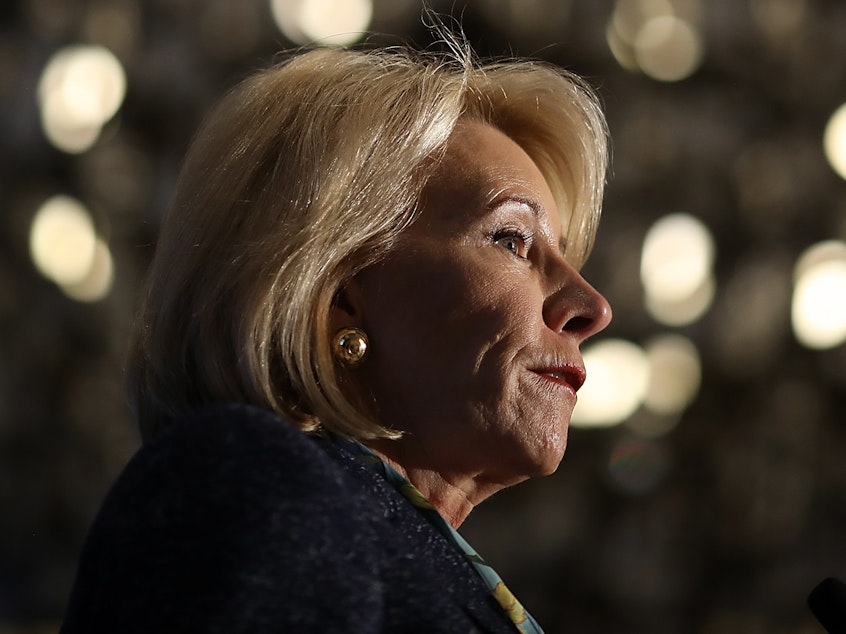

DeVos To Rescind Obama-Era Guidance On School Discipline

A federal commission led by Education Secretary Betsy DeVos recommends rescinding Obama-era guidance intended to reduce racial discrimination in school discipline. And, DeVos says, it urges schools to "seriously consider partnering with local law enforcement in the training and arming of school personnel."

President Trump created the Federal Commision on School Safety following the mass shooting in February at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla. While student survivors rallied for gun control, DeVos said early on that would not be a focus of the commission's work.

The final report highlights a single concrete gun control recommendation, pertaining to the expansion of "extreme risk protection orders," which allow household members or police to seek the removal of firearms from a mentally disturbed person.

The recommendations on discipline form part of a broader effort by the Trump administration and DeVos to back away from Obama-era policies aimed at reducing racial disparities in suspensions and expulsions. The commission says those polices made schools reluctant to address unruly students or violent incidents.

"Students are afraid because violent students were going unpunished," said a senior administration official, who spoke to reporters on the condition that he not be identified. DeVos instead called for a "holistic view" of school safety.

Sponsored

Civil rights and "discriminatory discipline"

The federal policies addressed in the report stem from 2014, when the Education Department under President Obama issued detailed guidance on "how to identify, avoid, and remedy" what it called "discriminatory discipline." The guidance promoted alternatives to suspension and expulsion, and opened investigations into school districts that had severely racially skewed numbers.

The guidance had its roots two decades earlier. After the passage of the Gun-Free Schools Act in 1994, more schools adopted "zero tolerance" discipline policies and added more police on campuses, particularly at low-income schools with many black and Hispanic students.

A growing body of research showed that being suspended, expelled or arrested at school is associated with higher dropout rates, and lifelong negative consequences. "Just one suspension can make a difference," says Kristen Harper, director for policy at Child Trends, a youth-oriented nonprofit. Statistics showed that these negative consequences fell far more often on students of color, disproportionate to their actual behavior. Black girls, for example, were suspended at six times the rate of white girls.

In the wake of the 2014 guidance, more than 50 of America's largest school districts instituted discipline reform. More than half the states revised their laws to try and reduce suspensions and expulsions.

Sponsored

And, a new analysis for NPR of federal data shows, suspensions indeed declined, particularly for Hispanic students. But the progress has been incremental, and black high school students are still twice as likely as whites to be suspended nationwide. So are students in special education.

School safety and school shootings

This conversation about discipline and civil rights ran headlong into a conversation about school safety after the killing of 17 students and school personnel on Feb. 14. The Marjory Stoneman Douglas shooting took place in Broward County, Fla., a district that had made a concerted effort to work with local law enforcement to reduce discriminatory discipline, cut suspensions and arrests and refer students to services instead of punishment. The program was called PROMISE. It went into effect before the Obama-era guidance, and was held up as a national model for discipline reform.

Emotions ran high when WLRN reported that Nikolas Cruz, who is charged in the killings, had been referred to the PROMISE program in middle school, but with no record of his receiving services. On a local radio show, Andrew Pollack, who lost his daughter, Meadow, in the shooting, called PROMISE a "cancer." "The leniency policy, the political correctness — that's a cancer that led up to February 14th of non-reporting of criminals that go to the schools in Broward."

The state's own post-Parkland school safety commission issued recommendations recently as well. That commission focused on physical security, like requiring teachers to lock classroom doors.

Sponsored

A broader walkback

Nikolas Cruz is white. He was also suspended, repeatedly, and transferred to alternative school. There was an armed school resource officer on campus that day, who remained outside rather than confront the shooter.

This announcement on discriminatory discipline, then, in some ways is better understood less in relation to the Parkland shooting and more as part of a series of actions by DeVos to reverse Obama-era guidance intended to protect the civil rights of students.

Under President Obama, the Education Department interpreted Title IX to protect transgender and gender-nonconforming students from discrimination. The department pushed campuses to take a stronger line in investigating sexual misconduct, also under Title IX, and issued guidance aiding schools' voluntary efforts to achieve racial integration.

DeVos has pulled back the guidance in each case, sometimes pleasing critics of federal overreach, sometimes in defiance of public consensus.

Sponsored

A new era?

Some of the federal safety commission's new recommendations, like directing resources toward mental health and social-emotional learning, actually echo the views of education experts who support discipline alternatives.

The question now is whether the government's latest reversal in direction on civil rights might bring a return to the days of zero tolerance.

Anurima Bhargava, a former Justice Department official who was involved in crafting the discipline guidance, says it was written to build consensus, with a great deal of consultation with school leaders and others. "So many people weighed in — there was nobody who was against it," she says. By that token, Bhargava finds it unlikely that the tide towards restorative and inclusive practices will fully reverse itself.

But during more than a dozen listening sessions, DeVos' safety commission heard from people who thought the push for alternative discipline had gone too far. Among them were Judy Kidd of North Carolina's Classroom Teachers Association, who said:

Sponsored

"Daily fights, concealed weapons and teachers assaulted are being ignored to reduce the number of incidents reported. This is unacceptable."

Without the federal government, there may be little pressure for change in places like Mississippi. That was the only state analyzed by Child Trends that saw an increase in suspensions each year between 2012 and 2016. Or in Allegheny County, Pa., where black students as of 2016 were suspended seven times more often than non-black students.

Activists like 18-year-old Nia Arrington, of the One Pennsylvania Youth Power collective, feel abandoned by this announcement. As a student in Pittsburgh public schools, in Allegheny County, she fought successfully against arming school safety officers.

"I don't think when these people talk about keeping students safe that they have all students in mind," she says. "They don't think about the harsh reality some students may have faced with gun violence. A lot of students have been traumatized by guns in this country — and by the hands of the police." [Copyright 2018 NPR]