Walk, bus or Lyft? Inside one Seattle commuter's daily decision

For this commuter, no one way to get to work is perfect. She must choose between speed and reliability, punctuality and concern for the greater good.

Experts say a more efficient system would let commuters serve all these competing needs at the same time. But it would require of us a very drastic, very Dutch move.

There are many different ways for Liz MacGahan to get to work. She lives near Yesler Terrace, and works as a copy editor in Belltown. Work starts at 9 a.m.

Most mornings, she walks.

“I feel like a farmer walking the fields, looking for what has changed … and what is different,” she said, pausing to look at murals or to consider a child's toy she found lying in a gutter.

When she walks (or rides a bike, as she sometimes does in the summer), MacGahan said she arrives at work energized and ready to dive into her work. The walk takes 40 minutes, which was cutting it a little close on the morning I joined her.

“I’m gonna make it! I’m gonna make it!” she said, speed walking the last couple blocks. "I'm gonna need a teleporter, but it'll be alright."

On another morning, the weather was bad, so she took the bus.

“It’s nice to sit on nice warm dry bus – and drink my coffee – and play on my phone,” she said.

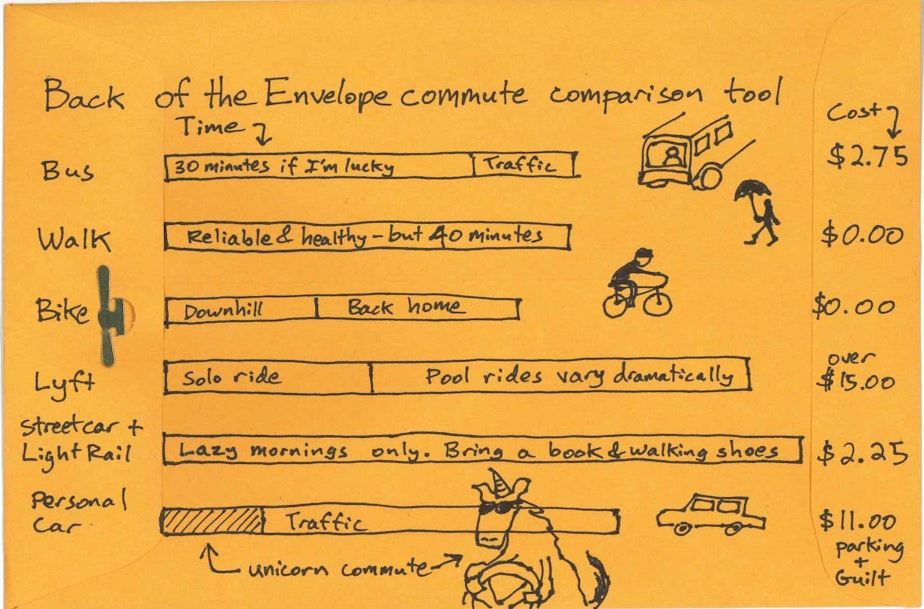

But the bus ride doesn't necessarily save her much time. When I joined her on her bus commute, it took 30 minutes, shaving a mere 10 minutes off her walking commute for a $2.75 bus fare. She said when the traffic’s bad, the bus takes as long or longer than walking.

Sponsored

MacGahan lives near the First Hill Streetcar Line, and has also taken that to Link Light Rail. But that two-seat commute, which drops her at Westlake Station, a significant walk from her Belltown office, takes longer than the bus.

One morning, she needed a reliable ride, to be on time for a job interview with a new editor. So she called a Lyft.

“I need to be there a little in advance to just not be flustered and weird," she explained, "And I needed to look a little bit more like a human person, professional, so that the prospective editor would not be scared.”

The Lyft ride took 21 minutes and cost her $16.

MacGahan has her own car, mostly for weekend trips to the Olympic Peninsula or to the mountains. She doesn’t use it for commuting, in part because she doesn’t want to pay the high cost of parking downtown, in part because she doesn’t like the environmental impact of driving. But this particular morning’s commute decision required compromise. So Lyft it was.

Sponsored

“What’s the moral high ground here?" she asked. "Walking, I think. And walking requires me to get up earlier than I wanted to for a 9 a.m. meeting. So that’s where I’m at.”

This is what it means to commute in Seattle. Sometimes, the best choices for you cause problems for others. Taking your own car or hailing a car adds traffic that slows down buses, making them less attractive to commuters. It’s a vicious circle.

Light rail helps a lot, but it doesn't go everywhere, and so buses end up doing a lot of the heavy lifting.

David Blum teaches Urban Planning at the University of Washington. He spends a lot of time studying places that move people better.

Sponsored

There’s one country that rises to the top.

“Nobody does it better than the Dutch. They are incredibly efficient at moving large numbers of people in and through urban areas."

And they do it mostly without cars, he said, before clarifying: “They have a lot of cars. They’re not a poor country.”

But he said planners in Dutch cities like Utrecht give cars good reasons not to come downtown.

First – they make it really easy to get to public transportation by investing in sidewalks and bike lanes. Blum said the Netherlands have an advantage in this regard, because cities there were never reshaped by cars in the way that Seattle was. He said it's more affordable to pay for sidewalks and bike lanes when they'll be heavily used, and that requires greater urban density than Seattle has.

And second – in big cities, the Dutch ban cars from their downtown streets during rush hour.

Seattle has just one major street downtown where cars (mostly) can’t go during the day: 3rd Avenue. That street's buses carry 52,000 commuters every day. During peak hours, the street carries seven times more commuters than a similar street with cars like 4th Avenue, and almost as many commuters as Sound Transit does on Link Light Rail in the tunnel through downtown.

Sponsored

So it works. But the need is too great for 3rd Avenue alone; it carries more buses than any other street in North America. As they leapfrog each other to reach crowded bus stops, they sometimes create their own bus traffic jams.

A Dutch solution would be to just make more streets into bus only streets, or make the whole downtown into bus-only zone. Blum says that would make buses more attractive to commuters because there'd be fewer cars to slow them down.

Then, when commuters like Liz MacGahan make their calculation about how to get to work on time, they'd know fastest, most reliable choice, is not a car -- it's a bus.