Ear-pulling. Neck-grabbing. A Seattle first-grade teacher is under state investigation and still in the classroom

Update: The teacher in this story was removed from the classroom, according to an email sent two hours after publication. Read that update here.

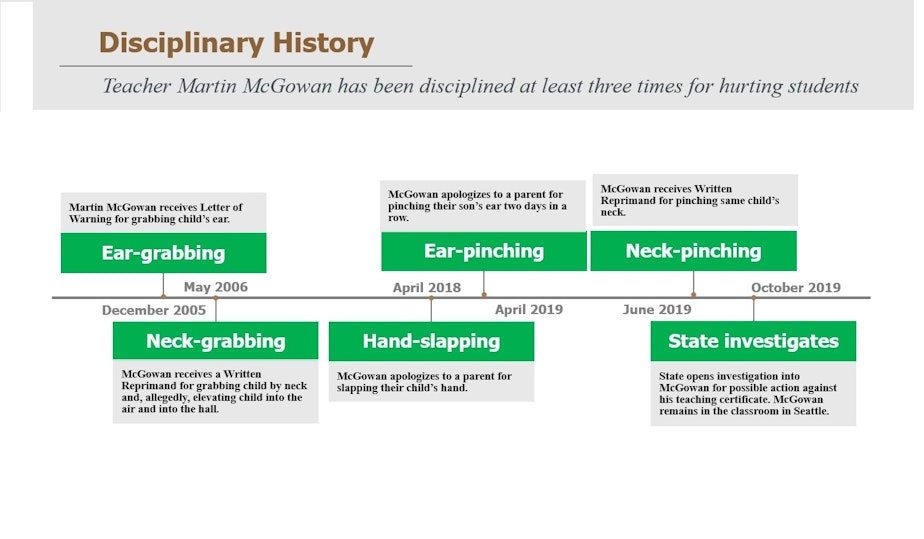

A West Woodland Elementary School teacher has been disciplined at least three times for hurting students over the last 14 years. The state is now investigating the abuse.

His case highlights flaws in how the district tracks and reports teacher misconduct.

Last school year, a 6-year-old Seattle boy couldn’t wait to start first grade at West Woodland Elementary School in Ballard. His assigned teacher, Martin McGowan, a nearly 30-year veteran of the school, had a reputation for doing fun activities, like making papier-mâché skeletons, taking kids on extra field trips, and bringing families out on his sailboat.

But within the first couple months of the school year, the boy’s parents said, his demeanor changed.

“He started not wanting to go to school,” his mother said. She figured it was because first grade was more academic.

“Looking back on it now, I wish I would have asked a little bit more,” his mom said. KUOW is not using the family members’ names at their request, to protect their child’s privacy.

One afternoon last April, the boy burst into tears when he got home from school, and told his mom that Mr. McGowan had pulled his ear.

Sponsored

“He said, ‘I got this math problem wrong five times, and every time I got it wrong, Mr. McGowan pulled my ear, and I just really wanted to go outside to recess,’” his mother recalled.

The boy demonstrated on his mother’s ear, a firm, painful yank on her earlobe.

When the mother asked if it had happened before, she said, her son looked startled that she didn’t know. “He said, ‘Mom, like hundreds of times.’”

“I was internally reeling,” the mother said. “‘Mr. McGowan has pulled his ear hundreds of times, and I’m just hearing about it now?’”

Sponsored

The next day, the boy and his dad went to school early to talk with McGowan, and asked him to stop the ear-pulling.

Mr. McGowan apologized, the father said. He said Mr. McGowan told his first-grader, “‘I understand, and it’s the right thing to do to tell an adult when there’s something that happened that you don’t like. I appreciate you telling me, and it won’t happen again.’”

That same afternoon, though, the boy told his mom that Mr. McGowan had pulled his ear – again.

“This time, in front of the class, as a joke, and [McGowan] said ‘I guess I’m not supposed to do this anymore,’” the mother said. “Shaming him publicly.”

The boy’s parents did not know that McGowan had faced discipline for yanking a child’s ear years before. They would learn this later, when they started digging into the teacher’s personnel file to figure out how the district was handling their complaints.

Sponsored

The parents said that when they reported the repeated ear-pulling to Kelly Vancil, assistant principal at West Woodland, Vancil agreed that it was a problem, and thanked them for telling him.

Vancil told them he had coached McGowan about similar issues over the last several years, the mom said, and that the teacher was very amenable to coaching.

McGowan, Vancil, and Principal Farah Thaxton did not respond to KUOW’s multiple requests for comment on this story.

KUOW has reviewed district records to determine how school officials handled complaints of McGowan’s misconduct toward students, including disciplinary letters, administrators’ warnings to the teacher, and email communications between multiple parents and administrators regarding recent and past abuse.

For the first-grade boy who complained last year, the touching stopped for about a month after they complained to Vancil, the mother said.

Sponsored

In an email from late April 2019, Vancil reminded McGowan that he was “to refrain from physical responses to student behaviors,” and “to look at the impact of your behavior on students.”

“Thanks for the reminder,” McGowan wrote back, and said that the assistant principal had helped “me put it in perspective and remember what trusting relationships are.”

But three weeks later, in mid-May, the boy “came home upset again, crying, and said ‘Mr. McGowan grabbed my neck,’” his mother said.

The child said his first-grade teacher had grabbed him by the scruff of the neck as he and other kids rushed to get their lunchboxes. It had hurt, the boy said, and afterward Mr. McGowan had told him to stop rubbing his neck. The parents kept their son home from school the next day, and set up a second meeting with Vancil.

At the meeting, the parents said, they asked McGowan to promise he would not touch their son for the rest of the school year: six weeks.

Sponsored

“And Mr. McGowan said, ‘I’ll try,’” the mother said.

“Dr. Vancil said, ‘Martin, we have a child and a family saying ‘don’t touch this kid.’ That’s one hundred percent. That’s not a ‘maybe,’” the mom recalled.

“And Mr. McGowan said, ‘I’ll try. But how am I supposed to help him with his math?’” she said.

Vancil brought Principal Farah Thaxton into the conversation. It took some doing, the parents said, but Thaxton finally agreed to move their child to a different first-grade class.

The parents said that when they asked whether McGowan would be disciplined, Thaxton told them she couldn’t discuss it, and referred them to policies on the district’s website.

Seattle Public Schools human resources chief Clover Codd has said that, as part of the district’s human resources “transformation” in the past 18 months, principals no longer handle investigations or discipline regarding serious misconduct. Instead, those cases will be escalated to the district level. Codd said the change was made prior to the 2019-20 school year.

Records show that as of last June, the district had assigned the investigation to Vancil, the assistant principal at West Woodland.

The mother wanted to figure out whether McGowan was going to face any discipline for hurting their child. She started filing public records requests. After going through all of the electronic records, the public records officer told the mom that he had found one more document: a paper copy in a different file. It was a 2006 written reprimand to McGowan from the school’s previous principal, Marilyn Loveness.

As the mother read it, “I was shaking. My heart was pounding and I couldn't even think.”

Loveness wrote that a parent alleged that McGowan “had placed your hands on a child’s neck with enough force to cause red marks as noted by the parents of the child. The child says that he was lifted from the ground as you took him to the hall,” Loveness wrote.

“When you demonstrated to me how you put your hands on his neck and shoulders, the force was enough to hurt,” the principal said in the reprimand.

Loveness cited a related incident: In December, 2005, she had talked with McGowan “about the inappropriateness of grabbing a child’s ear as a response to your frustration with his uncooperativeness.”

McGowan had been disciplined for the ear-grabbing at that time, as well: A letter of warning from Loveness that directed him to “not touch students in a way that could cause discomfort or the perception of impropriety.”

She “strongly” advised McGowan to seek counseling, and wrote that “it is important that students feel safe in your classroom and know that you will not become physically aggressive with them.”

The 2006 reprimand, the mother said, “was like reading our own story, but from 13 years ago.”

Email records show that the mom forwarded the disciplinary document to Principal Thaxton that day. The principal said that she had not been aware of the reprimand, and had not known McGowan’s history of hurting students.

“The principal not being aware of the disciplinary history of her own staff is pretty galling,” said education attorney Lara Hruska, who is helping the boy’s family in its dealings with Seattle Public Schools.

“It makes us all wonder what else are we not aware of? That's a big concern,” Hruska said.

Hruska said the district needs a better system of tracking staff discipline for serious misconduct so administrators can look out for and properly respond to new problems.

In a school board meeting this week, human resources chief Clover Codd said that the district is moving to an all-electronic record keeping system for disciplinary records and other personnel files – and making sure principals have access.

“It has not been [human resources'] practice to pass those [files] to the principal automatically,” Codd said at the meeting. She said her department plans to start providing those records to principals up-front beginning this summer.

One week after Vancil, the assistant principal, received McGowan’s 2006 written reprimand, he sent McGowan a new written reprimand for “pinching” the boy on the ears and neck.

Vancil wrote that McGowan admitted he was “very upset and should not have acted that way.” Vancil continued: “You also noted that you couldn’t believe you physically intervened with the same student that was the cause of previous complaints and said you would try your best not to touch a child again.”

In the letter, Vancil said that, in 2018, a different child had reported that McGowan had hurt him, “an allegation that you slapped the student’s hand. We met with a parent and you agreed that you should not have intervened in the way that you did and you apologized.”

These incidents, Vancil wrote, represented “continued and repeated misconduct despite the counseling you’ve received and written directives from me.”

“The District is concerned about the unprofessional conduct you continue to exhibit,” Vancil told McGowan.

State law and the teachers union contract say that the district must use progressive discipline to address misconduct: Because McGowan had received a written reprimand for hurting children in 2006, the district would be expected to discipline him more harshly for hurting a child again in 2019.

Instead, he got written reprimands both times. Asked why the district did not use progressive discipline to deal with continued physical abuse of children, spokesperson Carri Campbell said that “the recent written reprimand was provided prior to [Principal Thaxton’s] knowledge of the former incident.”

Email records show the West Woodland administrators were informed of the 2006 written reprimand at least one week before issuing the 2019 one.

Education attorney Shannon McMinimee, who previously was the head of human resources in Yakima Public Schools and legal counsel for Seattle Public Schools, said that up until a disciplinary action is officially issued, it can be increased or decreased.

“I have literally gone to the school and snatched a letter of reprimand out of the hands of a principal before she handed it to the employee,” said McMinimee, after discovering that an employee had received a prior reprimand – and that an unpaid suspension was the next step in progressive discipline.

State law requires that school districts report serious teacher misconduct — like physical abuse of students — to the state for possible action against the teacher’s license.

It took Seattle Public Schools six months after McGowan first admitted to pulling the first-grader by the ear to report the abuse to the state Office of Professional Practices.

The state has opened an investigation into the case.

Last fall, the boy and his family filed a police report regarding the physical abuse. The parents ultimately decided not to pursue charges.

KUOW contacted 20 other parents whose children have had McGowan as a teacher. Six parents and one student shared their experiences with us. None said they had witnessed physical abuse in his class, and three parents said they considered him an excellent, creative and dedicated teacher.

Four others, including a former student, said McGowan had humiliated and intimidated children in front of their peers. One mother, Liza White, said McGowan once kept the entire class in from recess because her daughter Morgen hadn’t finished her work.

Morgen, now a senior at Ballard High School, said that made the class turn on her. She said she hated first grade because of how McGowan treated her. The first-grade boy who had his ear pulled and neck grabbed last year wanted to avoid his former teacher, too.

To protect them from crossing paths, the West Woodland administrators set up a “student support plan” — a sort of school-level restraining order typically used to prevent student-on-student bullying.

In this case, the support plan was meant to protect a first grader from a teacher.

“If Mr. McGowan has any contact (verbal or physical), it will be reported to the administration right away,” the plan states. It requires that [the student] be allowed to use a bathroom far from his former teacher’s classroom, and bars McGowan from showing up at [his] after-school activities, as happened once. It was signed by the parents, principal and McGowan.

The boy’s parents said that the support plan is the only way they know how to help their son feel safer at school. But they also find it an unfair burden to place on the shoulders of a young child who now is asked to monitor and report interactions with a teacher.

“That’s not a normal way to be at school,” the mom said. “Little kids should not be the ones to carry that responsibility.”

Seattle Public Schools requires school staff to complete a series of online training modules at the start of each school year. This year, Martin McGowan has taken five, including how to handle diabetic emergencies, blood-borne pathogens, and asthma attacks.

Records show he has one mandatory training left to take, now 91 days past due: How to prevent child abuse.

Liz Brazile contributed reporting.