Former 'Ebony' Publisher Declares Bankruptcy, And An Era Ends

Ebony magazine was more than a publication — to black America, it was a public trust. It held a place of prominence in millions of African-American households whose members did not otherwise see themselves in the mainstream media. So back in 2015, when Johnson Publishing Company announced it was spinning off its flagship magazine, Ebony, and also its news magazine sibling, Jet, people knew something was up.

"They were just waiting for the other shoe to drop," the late Ken Smikle, a longtime observer of the Johnson Publishing Company's evolution, told NPR's Michel Martin.

Smikle founded Target Market News, a Chicago-based service that tracks black consumer power and patterns for the business market. He felt JPC was in for a rough ride. This week, the other shoe finally dropped: JPC announced it was filing for Chapter 7 bankruptcy protection. The company says it's selling the remainder of its assets, a comprehensive archive of photos from some of black America's most pivotal 20th Century moments, and a beloved cosmetics line that, toward the end, accounted for more than 40 percent of JPC's bottom line.

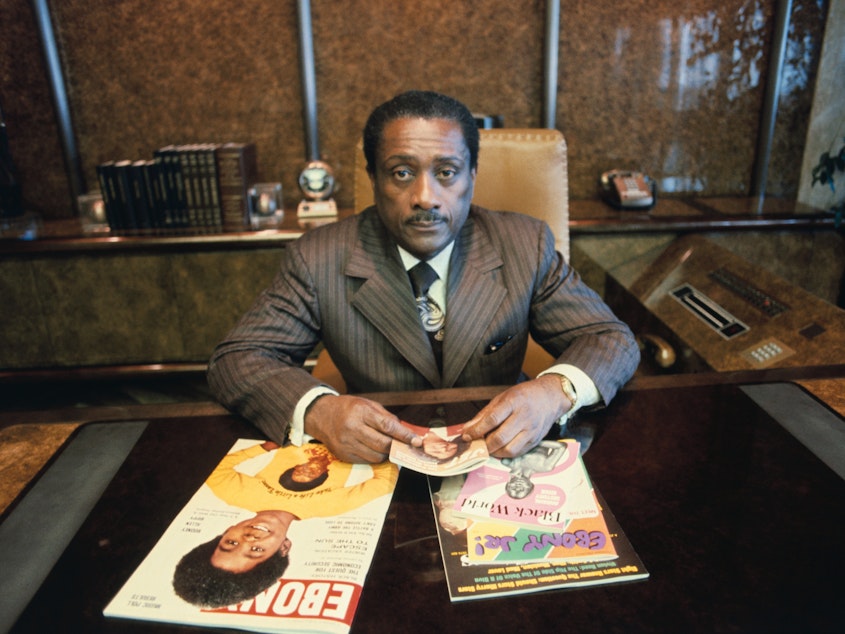

How did it get to this? Ebony has been around for so many decades, it saw the terminology for its target audience change from "Colored" to "Negro" to "Black" to "African-American." People thumbed through its glossy pages for stories of black success and achievement. Founder John H. Johnson used to say his magazines "gave readers the feeling that there were black people in other cities and in other countries like themselves who were doing well," he told NPR in a 2002 interview. "It inspired them to do better."

So there were doctors and lawyers, entertainers and sportsmen, pastors and politicians — including ones from black countries. Ebony covered Ivorian president Félix Houphouët-Boigny's state visit to the White House in 1962, and put his glamorous new wife on the cover next to Jacqueline Kennedy. Mme. Houphouët-Boigny shone. Black America swooned. It was a high point.

Sponsored

Changing times ... and the Internet

But times had begun to change. The civil rights movement gave way to the Black Power movement. The old assimilationist aesthetic became challenged by the new Afrocentric aesthetic. People's reading habits changed. By the time the Internet became a thing, it was only a matter of time before online ads began to siphon dollars away from the ones magazines had been commanding. Subscriptions of Johnson publications started to dwindle. (Eventually Jet, the magazine that shocked America with the gruesome lynching photos of Emmett Till, went digital in 2014 to cut costs.)

John H. Johnson died in 2005, and by prearrangement, the reins passed to daughter Linda Johnson Rice. Although she was literally raised by John and wife Eunice in the JPC offices, and was familiar with the magazine's business and editorial practices, Rice was unprepared — as were many other publishers — for the rapid shifts in the publishing industry, the downsizing and mergers. And perhaps most of all, the loss of those critical advertising dollars to the dreaded Internet. In 2010, Rice sold the iconic JPC Tower on tony Michigan Avenue (designed by a black man, built for a black man, as locals proudly pointed out), to Columbia College, and moved the staff to smaller quarters. In 2016 she sold Ebony, Ebony.com and Jet.com to Clear View Ventures, a Texas-based, black-owned private equity firm that promised to "position the enterprise for long-term growth. Our team," promised Clear View CEO Michael Gibson, "has a true understanding of the Ebony brand as well as its legacy."

Clear View had a less-than-clear understanding of the need to pay its freelance writers, who, because of the staff cuts and downsizing before the magazine's sale, had become Ebony's lifeblood. After several entreaties, then demands for payment, a group of contributors went public with its complaint and sued for payment. Clear View settled before going to court, but not before an embarrassingly effective social media campaign made the new owners national news.

Not a good start.

Soon after, despite its intention to keep most of the staff, many were let go. The magazines remain in Clear View's hands.

Sponsored

Selling the remains

It isn't just the magazine people will miss. John Johnson's wife, Eunice, created a traveling fashion show that drew tens of thousands of mostly black women for decades. Ebony Fashion Fair established a theme each year, and featured black models who strutted down the runways in clothes by Yves Saint Laurent, Bill Blass and up-and-coming black designers like Stephen Burroughs and Patrick Kelly. Money from the popular show went to black nonprofit organizations. Fashion Fair Cosmetics, the first high-end cosmetics line for women of color to be sold in department stores, was born when Eunice Johnson noticed her models mixing their own makeup shades before they walked the runway. She consulted with chemists to develop luxury makeup in deeper tones, and by 1973, had them introduced in department stores — not drug stores. Fashion Fair had sold fantastically well when white cosmetics companies were only selling foundations and powder that went the gamut from pale to paler. Then, some people began to realize there was a great, untapped market out there, and it had a brown face.

By the 1990s, former makeup artist Bobbi Brown introduced her own line of foundations that included deeper shades for women of color. And there was more competition: Canadian company MAC brought a line to U.S. stores that also became quickly popular with women of color for its rich palette. Fashion Fair no longer had the field all to itself. Then mega cosmetics chains like Sephora and Ulta arrived, marketing both in ubiquitous brick and mortar stores and ... yes, the Internet. There were problems with distribution. And not much was put into social media campaigns.

Fashion Fair faltered. Its original pink compacts and lipstick tubes looked ... dowdy. The line was refreshed and reintroduced in sleek bronze packaging to great enthusiasm several years ago, but either there wasn't enough product being made or it wasn't being distributed widely. (Explanations vary.) The end result was bare shelves, much to the consternation of worried customers and beauty bloggers. Some stores gave up — they couldn't afford to hold a space for product they weren't sure was coming.

Sponsored

Makeup artist Lashelle Farrington made what amounts to a video obituary for Fashion Fair. As she makes up her face and explains which Fashion Fair products she's using and shows how to apply them, Farrington muses about the increasing difficulty of finding the product over the past year. "I know that at the counter in my city, the person that works at the counter doesn't even know when they're going to get items in stock," she sighs.

JPC's move this week to file Chapter 7 is the final chapter in its storied history. If the tendered offer for the company's remaining assets is accepted, Fashion Fair and JPC's vast photo archive will be bought. And with that sale, whenever it occurs, the last vestiges of a vision that John H. Johnson made a reality for 77 years will come to an end. [Copyright 2019 NPR]