A homeless village in Seattle for Native people, with medicine garden and healing circles

There will be a medicine garden.

Traditional healing circles.

Native case managers.

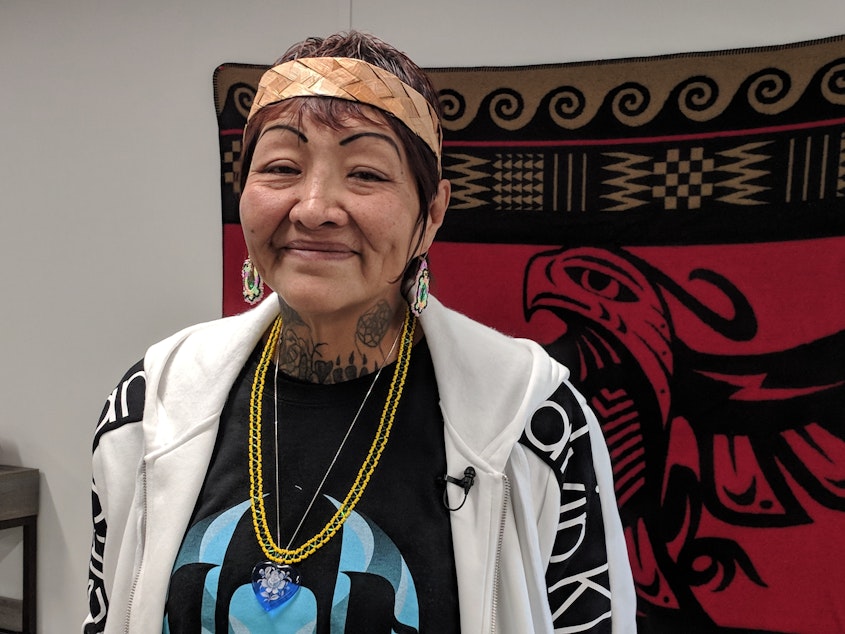

“This is Native housing for Native people, by Native people,” said Colleen Echohawk, executive director of the Chief Seattle Club, the organization which will provide on-site services.

Eagle Village, tucked away in Seattle's Sodo neighborhood, has modular housing that will serve Native people who are homeless. Up to 30 people will live here as they stabilize, access services and look for permanent housing.

The units in the village look like shipping containers with windows; they used to house oil workers in Texas.

Native people are vastly over-represented in the homeless population in King County: an estimated 10 percent of the homeless population in the county, but just 1 percent of the general population.

Starting in mid-November, Eagle Village will house people like Patricia St. Marks, 70, who has been homeless for about a decade.

Sponsored

“It’s been a really rough road for me to travel,” St. Marks said at the opening of the site.

"Knowing I'm going to have a place to live in Eagle Village, and move into my home one day, has put my heart into a permanent smile," she said through tears.

“Every day I wake up feeling free now," she said. "‘It’s okay to feel good,’ I tell myself. We don’t have to be ashamed anymore."

Listen to Patricia St. Marks talk about what Eagle Village will mean for her

St. Marks and her fellow residents will live in dormitory-style rooms at Eagle Village. Each unit has a bathroom, shower, beds, a mini-fridge and a microwave. There are also laundry facilities at the site.

St. Marks will also work there, helping other residents.

Sponsored

Residents will also have access to culturally appropriate services.

“We have been working with King County closely to address the disparity that we have within our homeless population,” Echohawk said.

“We decided that we would work together to offer a cultural response, to offer a cultural home for Native people right here in Eagle Village.”

“We'll offer a place where Native community can find a connection to tradition and to culture. We know that's important because Native people have experienced a lot of trauma," she said.

Echohawk said it’s unclear how long people will stay in the village. She said they won’t ask people to leave until they’ve found their next spot, somewhere permanent.

Sponsored

Jolene Neiss will be another resident at the site. She’s been homeless for about 15 years. She said it's an honor to be a part of the village, and she's grateful.

When asked what it’s going to be like to have a place to live after being homeless so long, she pulled out a compact mirror the size of her palm.

"It's like, having this, looking at this all these years, and then all of a sudden I get this room with a mirror like this," she said, tracing the outline of a large bathroom mirror in the air in front of her.

Sponsored

Neiss will live and work at the village. She said she wants to help others around her.

"The warmth of being acknowledged that you have feelings, you are heard, your voice is your person," she said, "and I will listen and I will help as much as I can because I was there, and I'm still there."

This is one of the first modular housing projects to open in King County.

“We are in a crisis, and we need to find creative solutions to bring people from the streets into shelter, into housing,” said King County Executive Dow Constantine.

Sponsored

He said modular units, like the ones at Eagle Village that sit on King County Metro property, can be stood up quickly and can be moved to a new location when needed.

It cost $3.3 million to stand up the village, including purchase of the modular units, according to the county. Annual operational costs will be about $800,000.

Funding came from multiple sources, including the Veterans, Seniors and Human Services Levy, the county’s general fund, and the state Department of Commerce.

Editor's note: Colleen Echohawk is a member of KUOW's board of directors.