How Rich Countries Are 'Hoarding' The World's Vaccines, In Charts

Healthcare workers first, along with residents and staff of nursing homes. Those people should receive the COVID-19 vaccine before anyone else, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Tuesday.

That recommendation applies to the U.S. But what about healthcare workers in other countries? Or the elderly with health conditions? Should a nurse in Peru, who's at high risk of catching the virus, be immunized before a person with low risk in the U.S. receives the vaccine?

Niko Lusiani, a senior advisor with the global aid organization Oxfam, thinks that strategy makes sense both scientifically and morally.

"I work in front of a computer, right now, in the safety of my home," he says. "I would be happy to withhold taking a vaccine so that a granny with a medical condition in Kuala Lumpur or in Lima, Peru, can get access to the vaccine. I think a lot of people will feel that way."

But, he says, right now the opposite will likely occur: Low-risk people in the U.S. will likely be immunized before many high-risk people in poor countries.

Sponsored

"Part of the reason is that rich countries are hoarding the vaccine supply," Lusiani says. "It's understandable, to a certain extent that you want to protect your own people. That being said, it's leaving a lot of people out."

When the pandemic began, rich countries went on a buying spree. Some have even called it "panic buying." These countries started making agreements with pharmaceutical companies to purchase experimental COVID-19 vaccines, even before clinical trials had finished. The details of many such agreements are not public, NPR has reported.

At the time, no one knew which experimental vaccine would work. So rich countries were hedging their bets. But now, it looks like many of the vaccines will be effective.

Vaccines from both Pfizer and Moderna appear to be more than 90% effective. Both companies have already asked the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to authorize emergency use of their COVID-19 vaccines. And AstraZeneca is likely not too far behind. Last week, the company said its vaccine was likely about 70% effective.

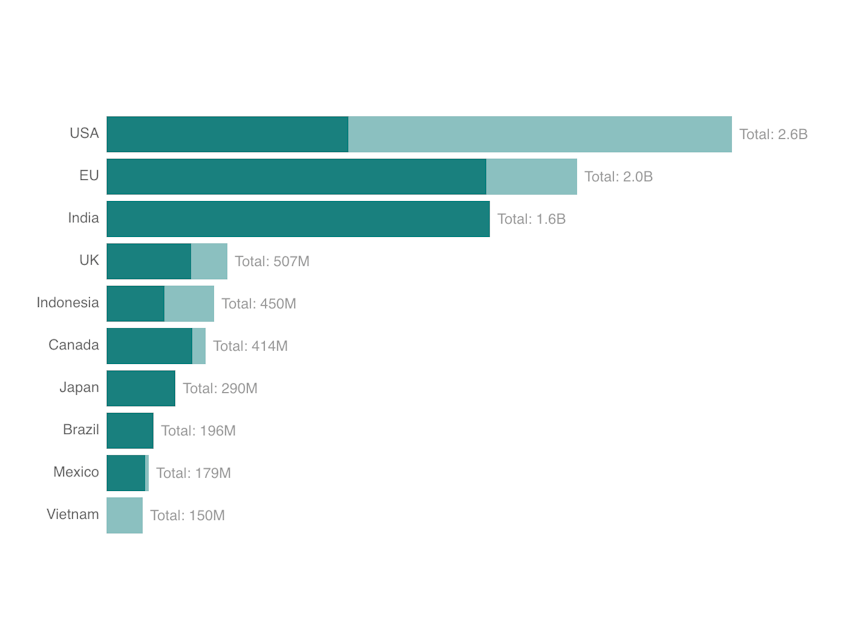

When these doses become available over the next year, some wealthy counties will likely end up with more vaccine than they need, says Andrea Taylor, who helps direct the Duke Global Health Innovation Center. The U.S. will probably have enough doses to vaccinate their population two times over. And Canada will have enough for their population five times over.

Sponsored

"Our data show that almost 10 billion doses have been reserved," Taylor says. "And the majority of those doses have been purchased by high-income countries."

For example, nearly all the Pfizer doses are going to rich countries. And the initial doses from Moderna are going to go to the U.S., Taylor says, leaving little vaccine for people in poor countries this year and possibly into 2022 as well. Some people likely won't be immunized until 2023, Taylor and her colleagues estimate.

"There are very significant inequalities," she says. "We have really not seen those inequalities close at all over the last couple of months."

That said, there's good news, says Kalipso Chalkidou, who directs global health policy at the Center for Global Development. Half of the doses of vaccine from AstraZeneca and its partner Oxford University is going to low- and middle-income countries. At least 500 million doses will go to India and 300 million doses will go COVAX, a World Health Organization initiative that helps poorest countries acquire doses.

For several reasons, the AstraZeneca vaccine is going to be critical for closing the gap in accessibility around the world, Chalkidou says. First off, this vaccine is also easier to transport and store because it requires only refrigeration. Moderna's vaccine needs to be stored in a freezer, and Pfizer's vaccine requires a special type of freezer that many clinics and hospitals do not have.

Sponsored

AstraZeneca is also rapidly scaling up manufacturing by sharing their technology with other vaccine makers. The company has already made an agreement with the Serum Institute of India, the largest vaccine manufacturer in the world, to produce hundreds of millions of doses next year.

Finally, the AstraZeneca vaccine is going to be a lot cheaper than other vaccines. It will like cost less than a fifth of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines.

"AstraZeneca has signaled that they want to make this available to people in in poorer countries at the lowest price possible, effectively at a cost. That's quite important," Chalkidou says.

Because if the world wants to end this pandemic, she says, it needs to produce billions of doses of not just a vaccine, but an affordable one. [Copyright 2020 NPR]