Seattle teacher abuse: What two school principals knew

A KUOW investigation found that two Seattle Schools principals welcomed or protected an abusive teacher.

James Johnson, a Seattle math teacher, was looking for a job.

Katrina Hunt, a principal, was looking for a math teacher.

It was last July, and Hunt, the principal at Washington Middle School, had just emailed school district headquarters, asking if there were teachers in the displacement pool, at the front of the list to hire.

“We have 2 math teachers left to place,” a human resources manager replied by email. Johnson was one of those teachers.

Sponsored

Rather than waiting until the displacement pool was empty, as principals often do to open the position to any candidate, Hunt replied right away.

Sponsored

“I would love to take Mr. Johnson,” Hunt responded eight minutes later. “I know his work and the situation. Please let me know how to move forward.”

It’s unclear what situation Principal Hunt was referring to in the email. She declined to answer KUOW’s questions.

Johnson’s situation was troubling. The previous year, the district found, he had punched an eighth-grader in the face at Meany Middle School in front of the class. He was also found to have sexually harassed female students.

In an email to KUOW, Seattle Public Schools spokesperson Carri Campbell said that Principal Hunt “was aware of the Meany incident” before Johnson started working at Washington. Hunt had a close contact at Meany: Her sister Chanda Oatis is Meany’s principal.

Back in July, the human resources manager told Hunt that Johnson was interested in the position. “Please let me know the best way for him to reach you," she wrote.

Sponsored

“We talked this weekend,” Hunt replied. “He got my number [from] Chanda.”

Johnson was hired at Washington Middle School the next day, district records show.

KUOW reviewed more than one thousand emails, investigation records, and other documents obtained through public records requests on teacher abuse in Seattle Public Schools. Among these records were emails showing that Hunt and Oatis took steps that helped keep Johnson in the classroom, despite his history of misconduct toward students.

These documents contradict what a top district official told frustrated, confused families in the wake of a KUOW investigation — which revealed a decade of misconduct allegations against Johnson.

Sponsored

READ: Seattle Schools knew these teachers abused kids — and let them keep teaching

The district insisted that Hunt was not to blame for Johnson’s hire.

“To clear up any misconceptions, he was not selected by the Washington Middle School principal,” said Clover Codd, the director of human resources for Seattle Public Schools, in an email to parents.

“Human Resources placed Mr. Johnson at Washington Middle School for the 2019-2020 school year,” Codd wrote, citing rules in the teachers union contract.

District spokesperson Tim Robinson elaborated by email: “He was placed just days before the start of school.”

Sponsored

Johnson was, in fact, hired at Washington in July, more than seven weeks before school started. And he was, contrary to district leaders’ claims, selected by Principal Katrina Hunt.

When KUOW sent the district Hunt’s emails about her interest in hiring Johnson, the district continued to insist that Hunt had no say in the hiring process, and that it had been a “forced placement.”

“They were simply connecting,” Robinson said of Principal Hunt and Johnson’s weekend conversation.

“That is not a forced placement. That is a principal choosing one specific staff member to fill a position,” said Shannon McMinimee, a former attorney for Seattle Public Schools, now in private practice. McMinimee has been head of human resources in the Yakima School District and led the legal department in Tacoma Public Schools.

Washington and Meany Middle Schools are down the road from each other, and some of Johnson’s former students from Meany now attend Washington.

Sponsored

Hunt “could have said, 'Wait, we can’t have him here. Our student population overlaps, it will be dangerous,' and HR would’ve found another place for him,” McMinimee said.

Johnson was escorted from Washington Middle School the day after KUOW published its first investigation on teacher abuse. New allegations against him had surfaced from this school year at Washington, the district said, including “aggressive actions toward students,” and failing “to maintain professional boundaries with students.” He is now on paid administrative leave for the third time in two years as those allegations are investigated.

Students and parents said they had already complained to the school administration for months about Johnson’s behavior. KUOW spoke with seven parents and students who said that nothing seemed to come of their reports of misconduct against students.

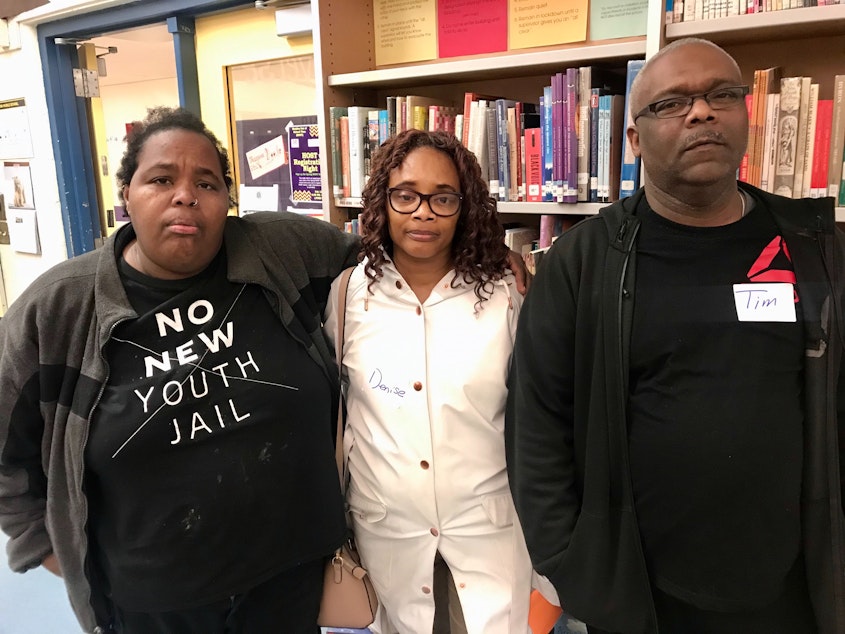

Denise Dailey, whose grandson attends Washington, told KUOW that he had a run-in with Johnson just a few weeks ago with some similarities to the punching incident at Meany.

[Read other stories from Ann Dornfeld's ongoing investigation into abuse in the classroom.]

When Dailey’s grandson interrupted Johnson’s class to retrieve his belongings, Dailey said, Johnson grew angry, shoved the boy out of the classroom, and called him the ‘n’ word. Both Johnson and the student are black.

Dailey told KUOW that when she tried to talk with Johnson by phone about the incident, he hung up on her twice. When she then called Washington Principal Katrina Hunt, Dailey said, Hunt “said she’d talk with Johnson and get back to me.”

After a KUOW investigation into Johnson’s long disciplinary history published January 24, Dailey said, she made an appointment with Hunt to follow up on her complaint. When Dailey arrived for the meeting, she said, the school secretary turned her away, saying “Ms. Hunt said she wouldn’t talk about anything regarding Mr. Johnson.” Dailey said now she does not know where to turn.

K.L. Shannon is the vice-president of the Washington Middle School PTSA and a chair of the Seattle/King County NAACP.

Shannon said her nephew Jakwaun, an eighth-grader at Washington, told her that Johnson seemed to target kids of color. “Belittling of black boys, black boys being kicked out of his class constantly, my nephew being one of them,” Shannon said.

“I know right now that if the children were not just black and brown, [Johnson] would not be in their school,” Shannon said – he would already have been fired.”

Principal Katrina Hunt turned down KUOW’s interview requests.

I

n November 2017, a parent at Meany Middle School was looking for assurance that their son was being protected from James Johnson after a reported altercation.

“As discussed per our phone conversation [our son] being physically grabbed and yelled at from Mr. Johnson was unwarranted and unacceptable,” the parent wrote to the assistant principal. The email was forwarded to Principal Chanda Oatis and then-Superintendent Larry Nyland. The district redacted the parent’s name.

“[Our son] is a very ‘tough’ kid and when speaking to him on this incident, he actually started to cry,” the parent told the assistant principal. “When someone you trust violates you that has an effect on kids.”

“You confirmed with me that it was not a restraint hold and that Mr. Johnson based on the video acted inappropriately and you would be following through on his inappropriate actions,” the parent wrote.

“I would like to know in writing what will be done about this so that this does not happen between Mr. Johnson and my son again or another student.”

Superintendent Nyland forwarded the parent’s email to other district officials, including Oatis’s supervisor, Sarah Pritchett, and Pritchett’s supervisor, Michael Starosky.

There is no indication in Johnson’s personnel file that he was disciplined for the incident.

Two months later, Johnson punched a student in the face.

According to a former teacher at Meany, as the district investigated the punching incident, Principal Oatis seemed to be “working very hard to exonerate” Johnson.

“Chanda pressured me frequently about writing letters of support for Johnson during this whole process,” said the teacher, who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of reprisal by the district.

During meetings, “she would just sort of drop it in, like, ‘Hey, if you think about it and you have anything to say, make sure you take a minute and write a letter of support for Mr. Johnson.’”

The teacher ignored the requests.

“That is totally inappropriate,” said education attorney McMinimee.

It can be a fireable offense for a supervisor to solicit positive letters for an employee accused of serious misconduct, McMinimee said, in part because it opens the district up to liability. “It interferes with the disciplinary process, and is retaliation against all of the staff and student witnesses,” she said.

Oatis also spoke on Johnson’s behalf at his district disciplinary hearing for the punching incident before Superintendent Nyland. The human resources department, led by Clover Codd, had recommended that Johnson be fired for the assault. Nyland instead gave him a five-day suspension.

After Oatis informed parents that Johnson would return to the classroom in late March, parents protested. Along with punching a student, they said, Johnson had sexually harassed girls and threatened kids.

“It is alarming and unacceptable for him to be back in the classroom,” one parent wrote.

Oatis replied to the parent that this was not the first time that she’d heard allegations from Meany students regarding Johnson.

“Earlier this year, some concerns were shared anonymously with our counselor,” by girls at the school, Oatis said. “I addressed those concerns with the teacher immediately. Since that communication no other incident was reported.”

Two days after Johnson returned to Meany, however, he was back on administrative leave: This time, while the district investigated sexual harassment, grooming and intimidation allegations.

After a district investigation found most of the sexual harassment claims against Johnson to be true, the human resources department recommended against discipline. Oatis had already disciplined Johnson earlier in the school year for misconduct, they said, including “showing favoritism to students, calling students ‘pet’ names, and touching students on elbows and shoulders,” read a district letter.

“The principal had already implemented corrective action and counseling for these alleged behaviors (that were reported to her previously) and we could not go back and reimpose a harsher discipline,” human resources director Clover Codd told KUOW by email.

Although Oatis had previously disciplined Johnson for how he touched, treated, and talked to students, and knew that Johnson had allegedly grabbed and yelled at a boy at Meany the previous fall, she did not mention these incidents during a state investigation.

The state Office of Professional Practices was considering action against Johnson’s teaching license for the punching incident. In April 2019, Oatis testified under oath before a state investigator.

“Ms. Oatis was asked if there were any issues prior to the incident involving Mr. Johnson and the student he was alleged to have been in an altercation with,” wrote the investigator in his report.

“Ms. Oatis advised that Mr. Johnson was a good teacher and she had no disciplinary issue with him prior to the physical incident he had with a student in January 2018.”

When KUOW sent Office of Professional Practices Director Catherine Slagle the evidence that Johnson had, in fact, been disciplined for misconduct at Meany prior to the punching incident, she sighed.

“It appears someone is lying,” Slagle said, explaining that either the principal misinformed investigators, or the sexual harassment discipline Codd cited never actually happened.

Johnson currently faces a proposed eight-month suspension of his teaching certificate, which he has appealed.

Principal Chanda Oatis declined KUOW’s requests for comment.

“She is not interested in speaking with you,” wrote Seattle Public Schools spokesman Tim Robinson in an email. “The same goes for Principal Hunt.”

//

Since KUOW’s initial investigation into Seattle Public Schools’ lenient discipline of abusive teachers, district officials, including Superintendent Denise Juneau and human resources director Clover Codd, have insisted that the district has turned over a new leaf in the year-and-a-half since Juneau took over.

“Over the past 18 months, I have charged Human Resources with improving processes and procedures that put student safety at the heart of all decision making,” Juneau told staff members in an email regarding the KUOW investigation.

As part of what the district calls its “HR transformation,” Codd said, as of this school year, principals no longer handle investigations and discipline of serious staff misconduct. Instead, they escalate such issues to district headquarters.

But at Washington Middle School, many parents and students question whether that’s so, given what they said they’d already told school officials in the past few months about how Johnson treated kids.

Many parents and students have demanded to know why school leaders may have protected Johnson, or looked past his misconduct. By many accounts, Johnson could be an effective math teacher, and, at Meany, had an after-school program to mentor black boys. The boy he punched at Meany was in that program.

At a PTSA meeting Monday night at Washington Middle School, more than two dozen parents turned out to ask who knew what about Johnson, and what they did or did not do about it.

The parents said they’d hoped Principal Hunt would be there to answer their questions. It was, they said, the third PTSA meeting they’d invited her to since the scandal broke. Instead, Rainey Swan, executive director of the principals union, appeared on Hunt’s behalf. Swan asked questions and took notes that she said she would share with the principal.

Charlotte Schubert, whose daughter is a 7th-grader at Washington, said she expects more than an apology for the district letting a teacher with a history of abuse work at the school.

“In my view, there are systems failures, and there are personal failures,” Schubert said. “When people fail to keep children safe, they need to be held accountable.”

Do you know about verbal, physical or sexual abuse of students in public or private schools? We’d like to hear your story. Contact Ann Dornfeld at adornfeld@kuow.org or (206) 221-7082.