How sweating manikins can help us prepare for a warming world

Put simply, humans are complicated, and our feedback is subjective. Put a jacket on someone and ask them if it's warm, cold, breezy, or stuffy, and you'll get a range of answers.

To get quality data, you need a sophisticated tool — a tool that can sweat.

Rick Burke operates in a world of niches, from compost warehouses, oceanic cable sensors, to thermal manikins. If you ask him about how he ended up at that unique intersection, he'll say the strategy is to solve one need, then find others seeking a similar solution.

"We're blessed by having this niche where there's not a lot of competition," Burke said while standing outside "manikin land" at Thermetrics' Interbay office in Seattle, where his company produces highly specialized manikins.

"There are only a few organizations in the world that make products like this."

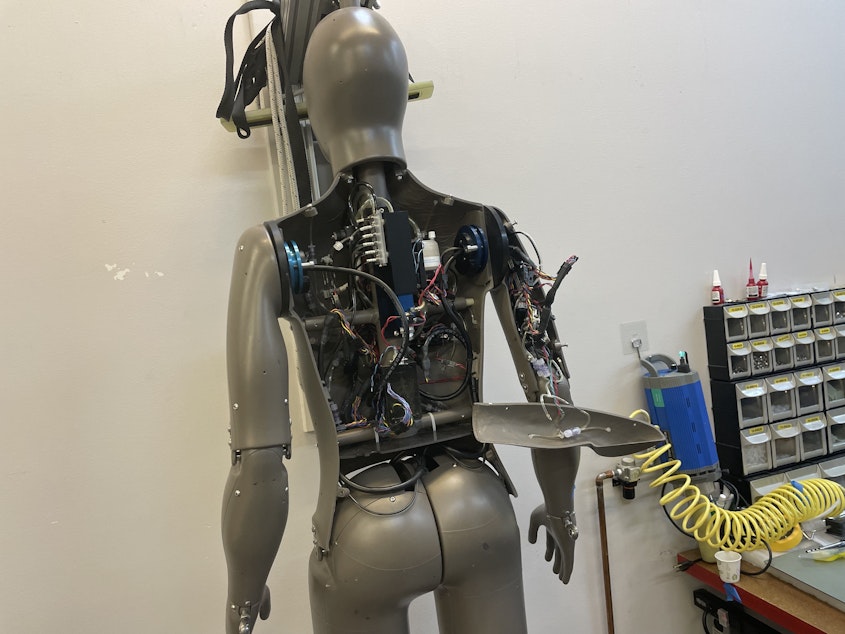

On a Soundside tour through Thermetrics, a tableau of disembodied hands, arms and faces, are spread across tables. Each one is packed with nozzles, tubing, and electronics. These manikins don’t just wear clothes, they test their limits.

Take a manikin affectionately named Bernie, for example. He's used to test firefighting equipment in the most extreme conditions.

Sponsored

"This is a manikin that we make out of specialized materials so that we can directly expose it to fire," said Burke. "It can sit in a five to ten second fire without any damage to the manikin."

Why is this necessary? For one thing, you can’t test the flammability of clothes on people. And humans are complicated, and our feedback is subjective.

That lead Thermetrics to their news manikin, ANDI, who fills one very specific niche: ANDI can sweat.

"We build Andy with a cooling system so that we can pipe water through it," said Burke. "You can liken it to blood, or just some way of actively pulling the heat out so that the mannequin doesn't overheat."

Burke says that this kind of work originated decades ago with the U.S. military, who sought to design climate-tailored equipment during deployment. Eventually, the science of designing comfortable, high-performance clothing extended to everyone. Some challenges have taken a lot longer to solve, and that’s where advanced manikins have come in to help.

Sponsored

"I can tell you that when we turn the sweat up, it's a lot. We can drown you," said Burke.

Over the years, the underlying model of thermal manikins has led to some more specialized products -- like a sweating derriere named Stan, who's used to test heated car seats. But some of the most novel uses of a manikin like ANDI aren't in a textile laboratory setting.

"We wanted to use Andy to see how a human body responds to environments," said Konrad Rykaczewski, who is using ANDI to study how heat affects the human body at Arizona State University.

"Phoenix is so hot that we are not ethically able to do a lot of experiments with prolonged exposures that many people are exposed to on a daily basis -- because they're just dangerous."

Rykaczewski and others at ASU are deploying ANDI into hot urban environments like parking lots, where they can get important data on how the factors that contribute to overheating and serious health risks like heatstroke.

Sponsored

Their hope is that this research can find ways to make places like cities more hospitable to heat, and also develop a series of heat sensors that can be deployed to other urban spaces. These sensors can convey more information than standard air temperature, allowing cities to prepare for a variety of factors that create and transfer heat.

Here in Washington, the 2021 heat dome that caused roughly 800 deaths across the Northwest and British Columbia and was exacerbated by a historical lack of air conditioning built in the region.

Rykaczewski said there are many safety considerations that need to be taken into account when it’s hot outside, and being able to better measure health impacts will help inform behavior and policy.

"Are kids allowed to go outside or not? Is the playground safe or not? Should you have a soccer game, or should you cancel it?" he said. "Should workers continue on a construction side, or should they stop? If you have just these blank, broad recommendations, for some people they're too conservative, and for others they're too lax."

Listen to the full Soundside segment by clicking "play" on the audio icon at the top of this story.