Invasive crab population keeps booming in Washington

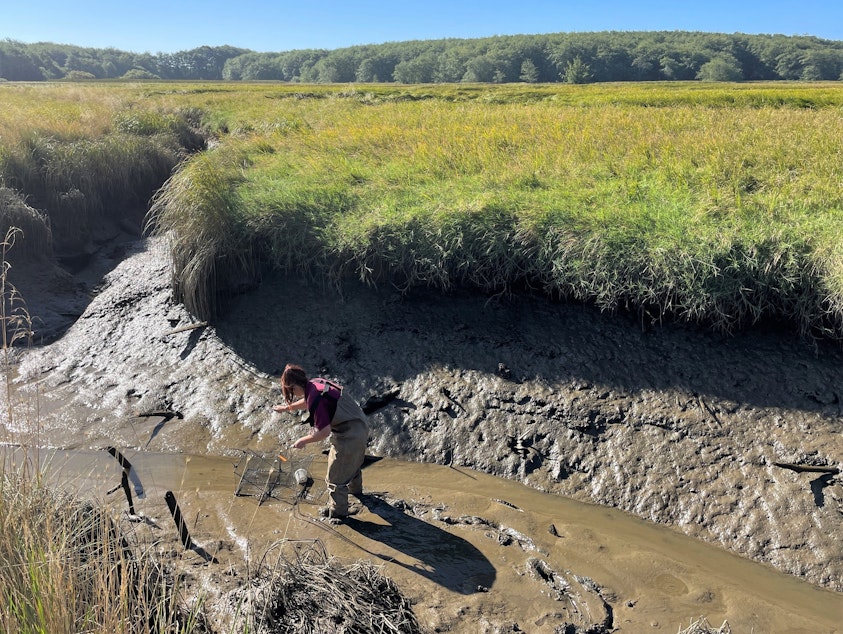

Trappers have caught nearly a quarter million European green crabs in Washington waters so far in 2022.

This year’s record-smashing tally of the invasive species—248,000 caught as of Oct. 31—is more than twice the total caught last year along Washington shorelines.

2021 had seen a massive increase in the unwanted crabs, with 103,000 turning up in traps in the state.

That trend continued in 2022, with Willapa Bay on Washington’s outer coast surpassing Lummi Bay on Puget Sound as a hotspot for the habitat-destroying, shellfish-crunching crabs.

Biologists say the growing haul reflects an increase in trapping efforts as well as booming numbers of crabs. Trapping increased after Gov. Jay Inslee declared a green crab emergency in January and the state Legislature dedicated millions to combating the pinchy invaders.

European green crabs dig up underwater habitats like eelgrass beds and attack commercially valuable species like Dungeness crabs. The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the green crab as one of the world’s most destructive invasive species.

Sponsored

“Based on the information we have, it has been a rapidly expanding population,” said Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife biologist Allen Pleus, the state’s green crab incident commander.

Actual populations of the crabs are unknown, since many animals elude trapping.

The Makah Tribe reported a seventeen-fold increase in green crabs on its Olympic Peninsula reservation in 2022.

“This was a big shock,” said Makah Tribe biologist Adrianne Akmajian. “The numbers of crabs we were catching just went crazy.”

Sponsored

Trappers to the north on Vancouver Island have found even larger numbers of the crabs over the past 12 months. Since November 2021, field crews have hauled in 439,000 European green crabs in just two locations: Clayoquot Sound on the island’s west coast and the Sooke Basin, about 20 miles northwest of Port Angeles, Washington.

“At the majority of our sites in Clayoquot Sound, we rarely catch anything in our traps other than green crab,” biologist Crysta Stubbs with the Coastal Restoration Society said by email. “This could be demonstrating that they are taking over entire estuaries and predating on or pushing out other native species, however we cannot say that definitively.”

She called the island’s infestation “intense.”

“There's hundreds of thousands of these green crabs,” Councilmember Terry Dorward of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation in Tofino, British Columbia, told KUOW in March. “It should be a national outcry here.”

“Those are very significant populations, much higher densities than we're seeing so far in Washington state, and an example of where we don't want to go,” Pleus said.

Sponsored

In Washington, a continuing hotspot has been an artificial saltwater lagoon on the Lummi Reservation near Bellingham. Crab teams caught 86,000 crabs in that sheltered habitat in 2021 and have hauled in more than 70,000 so far this year.

State wildlife officials say Lummi Sea Pond trappers are now finding mostly older crabs, and few young ones, which might bode well for getting that population under control.

Puget Sound and other inland waters of the Salish Sea are somewhat protected from new influxes of the crabs. The freshwater outflow of the mighty Fraser River, just north of the U.S.-Canada border, floats on top of denser salt water and tends to push crab larvae and other floating objects out the Strait of Juan de Fuca toward the Pacific Ocean.

Outer coastal areas lack such a deterrent.

Sponsored

“There is no bottleneck for larvae to be coming into our coastal areas—Willapa Bay, Grays Harbor, Makah and others,” Pleus said.

“Harvesting green crab alone is unlikely to decrease the population in the long run,” according to the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. “Harvested numbers are quickly replaced by supplies of larvae delivered on ocean currents.”

European green crabs arrived in San Francisco Bay around 1989, possibly in the ballast of a cargo ship, and have been spreading north since then.

In July, green crabs were found in Alaska for the first time, on the Annette Islands Reserve near the southeastern tip of the Alaska Panhandle.

In August, Oregon officials tripled the daily catch limit from 10 to 35 green crabs to encourage recreational harvesting. Though adult green crabs are smaller and less meaty than Dungeness crabs, agencies have tried to encourage their use as food, even producing green crab cookbooks.

Sponsored

READ: Can’t we just eat those invasive crabs until they’re gone? (Probably not)

“I don't think the species is going away,” Akmajian said. In addition to controlling its numbers, Akmajian said she hopes Makah tribal members can, some day, make use of the increasingly abundant crustacean.

“This is their traditional lands and territories where they've been for millennia and learning to use what is available,” she said.

For now, the Makah Tribe’s trappers freeze the green crabs to kill them and send about 200 a year to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts for genetic analysis. The rest, as elsewhere, go to the landfill.

This story is Part 5 of our series on invasive species in Washington state: “KUOW's League of Murder Creatures.”