Japanese American survivors revisit a troubling past and vow to protect the Idaho prison camp where they were held

I

was looking for a name on an exhibit that's honoring more than 4,000 people who were incarcerated in the middle of Idaho farmland, at an American prison camp that most people don’t know about or would prefer to forget.

Each name printed on the 7-foot panel belongs to a first-generation Japanese person who was held at the prison camp in Minidoka, Idaho, during World War II. The exhibit acknowledges their risk of leaving Japan and creating a community here in America. They worked hard, despite prevailing anti-Japanese sentiment, to pursue their version of the American Dream.

Then in 1942, with little warning, they were rounded up and imprisoned without being charged with a crime, told where they were being taken, or when they might return to their homes, businesses, and lives.

I was squinting and scanning the middle of the three panels for a particular name, as I dodged the heads of people in front of me. They were looking for the names of their loved ones. I was looking for a name I heard only a few times growing up.

A fellow pilgrim asked me who I was looking for. I hesitantly said, “my honorary uncle, Shosuke Sasaki.” I moved to the front and we looked for Uncle Shosuke. It’s easier to read the names now, but it still feels like an endless list. My fellow pilgrim pointed at the top right corner of the final panel. Once I saw it, his name, “Shosuke Sasaki,” stood out from the rest and seemed to glow in the sunlight.

Seeing his name there among the thousands of Japanese Americans who were held at Minidoka sent a wave of emotions surging through me. I had felt this way before when writing stories and researching the incarceration of Japanese Americans at prison camps across the United States. But I didn’t realize that visiting Minidoka would stir so much anger, sadness, and pain.

Sponsored

I understood for the first time the power a place can hold. Little did I know, coming to this site would unlock a missing piece of my family’s history.

Internment or imprisonment

During World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the U.S. Army to remove all persons of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast and imprison them without due process of law. This order forced more than 125,000 Japanese Americans from their homes and placed them in prison camps. Two-thirds of these people were American citizens.

NOTE: KUOW does not describe Executive Order 9066 as an “evacuation” or call the camps “internment camps.” These terms gloss over the intensity and horrors that occurred to the Japanese American community during WWII.

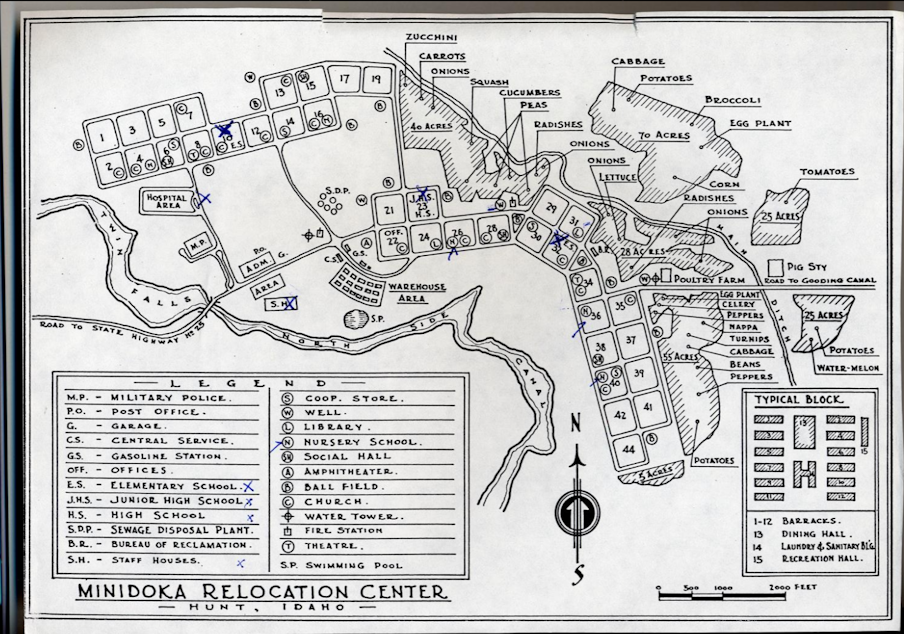

Many Japanese Americans who lived in the Pacific Northwest were held in Minidoka, about 150 miles southeast of Boise. Hundreds of survivors and their descendants make annual pilgrimages to the Minidoka National Historic Site.

Sponsored

This year was the first pilgrimage since the trip went on hiatus due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It was also my first trip to the site where at least one of my ancestors was held during WWII.

But the experience of visiting Minidoka and the desolation and isolation of what Japanese Americans experienced at the camp could soon change forever. A proposed commercial scale wind energy project would put 400 wind turbines right next to the site. A growing coalition of Japanese Americans is pushing to prevent the development and protect Minidoka, despite the horrible memories of living there that have been passed down for generations.

Embarking on a personal pilgrimage

On the morning of July 4, I prepared for a three-day trip to Minidoka along with 200 other pilgrims as part of the annual pilgrimage. As I got ready for the trip, I thought about what it would be like to make this journey in 1942, not as a visitor packing for a brief visit, but as someone who was forced to relocate to a place I did not know for an uncertain period of time.

Sponsored

Many families were given 24 to 48 hours. One could only take what they could carry. Everything else would be left behind, maybe forever.

I finished packing my suitcase, grabbed my recording gear, and loaded it into my car. I say goodbye to my dog, Pulitzer. He was looking extra worried, as the suitcase meant I would be gone for a while. I told him I would see him in a few days. If it had been 1942, that would have been a promise I wouldn’t have been able to make or keep.

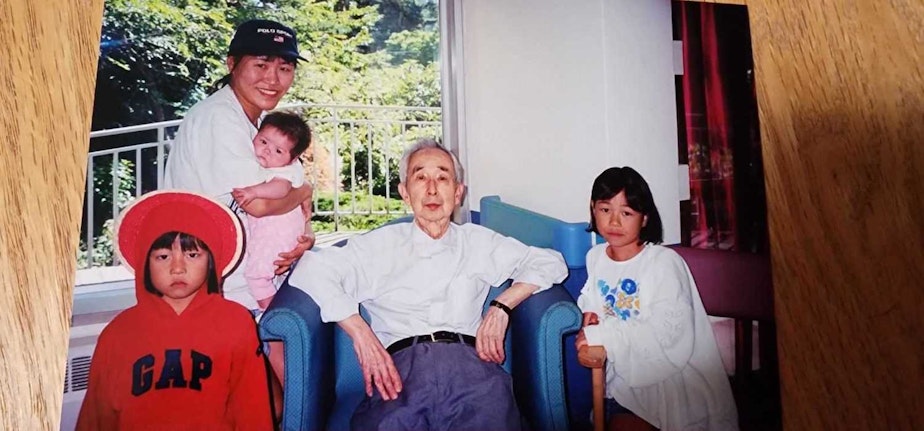

Although “Uncle Shosuke” was not really my uncle, he had a lot to do with my family ending up in the Northwest. One of the reasons my grandmother, who lives in Kobe, Japan, allowed my mother to study at the University of Washington was because her distant relative, Shosuke Sasaki, lived in Seattle. Growing up, I heard his name often but knew little about him. He died when I was 3 years old.

Last year, when working on another story, I found his name in a database that placed him at Camp Harmony, or the Puyallup Assembly Center on the Washington state fairgrounds. Barracks were next to a wooden roller coaster, under the grandstand, and on the racetrack. It was a temporary holding site before those who were imprisoned were sent to permanent sites like Minidoka.

Sponsored

We never knew where Uncle Shosuke went after Camp Harmony. I asked my mother why she does not know more about his experiences. She explained that she didn’t like to ask him about it, because remembering seemed to cause him pain.

I drove over the North Cascades and the world outside transformed from the wet, green of Western Washington to the dry, brown farmland east of the mountains.

Minidoka’s hidden history

Sponsored

There isn’t much left at Minidoka National Historic Site — a few weathered historical buildings, including a replica of a guard tower. Most of the site is open farmland that extends out to the horizon.

The hot sun beats down on the 200 people who have made the journey. For a city girl like me, this looks like the definition of isolation. I think to myself, the isolation is likely why the government picked this location.

Fujiko Gardner is a survivor of the Minidoka prison camp. She made the journey to Minidoka with her family.

“Most of us, when we arrived at Minidoka, were shocked. Coming from Washington, we were used to beautiful greenery and green trees. It was a shock getting off the train,” Gardner said. “All you could see was miles and miles and miles of dry land and lots of sagebrush.”

When Executive Order 9066 was issued, it wreaked havoc on her family. Gardner was born in the United States, the youngest of 11 siblings. Like Uncle Shosuke, Gardner and her family were initially sent to Camp Harmony.

“I had my tenth birthday at Camp Harmony,” she said. “I saw my father change. I truly believe that if he found a way he would have ended his life. Because of the time in that Camp Harmony, he changed tremendously.”

Fighting for captor and country

Gardner said her father became depressed. When he returned to the barrack from the mess hall, he could see a guard tower with a soldier holding a rifle. Gardner’s oldest brother was the only person in her family who did not go to the camp. He enlisted in the army before the war.

“I think my father was angry about that,” Gardner recalled. “His own son is wearing the same uniform as the guard in the tower. It doesn't make sense, does it?”

Gardner said, while her father’s mental state declined, her mother made up for it.

“Financially, we were poor. I could honestly say that we were rich, in so many other ways. Thanks to my mom. She is the one who showed us the strength and endurance,” Gardner said. “Many people say that it was the mothers who had it under control.”

After three months at Camp Harmony, Gardner and her family were moved via train to Minidoka.

Two of Gardner’s older brothers, Mitsuru and Masaru, were later drafted from the camp into the military. They were part of the renowned 442nd Infantry Regiment. It was composed almost entirely of Japanese American soldiers and is the most decorated unit in U.S. military history. Her brother, Mitsuru, was killed in action when serving in Italy, one month before VE (Victory in Europe) Day in 1945.

Gardner said the U.S. government failed her, her family, and her community.

“That's the horror of this all," she said. No American citizen should have had to go through what we did."

Making a life in the middle of nowhere

On our pilgrimage, we toured the historic Block 22. It holds two wooden buildings that look like shipping containers. One served as a barrack, the other as a mess hall. Inside the barrack, every step you take creaks and echoes.

Multiple family units and apartments were housed together. There were no walls in between the units, so people hung bedsheets. But the bedsheets did not block out the sound. If a newborn baby cried, or a sensitive family discussion was taking place, everyone in the barrack could hear it.

The buildings were built using fresh, green wood, and when the wood dried, it shrank, leaving gaps in the walls. A single dust storm could cause about an inch of sand to build up inside the barrack. People stuffed newspapers in the cracks to keep the sand out. Gardner remembers the dust storms. She said the elders also planted grass and flowers to try to help.

“They knew that they had to either throw grass seed out there to keep the dust down. They were industrious people,” she said. “They're not gonna sit around and mope around and, you know, cry about the horrible conditions we have to live in. They really took time to do something about it to make it a beautiful place to stay in.”

Gardner said it is critical to share these experiences with younger generations.

“Every opportunity I get, I have to, you know, tell my story, because it's not just my story,” she said. “It's all of the Japanese American story.”

Exploring generational trauma

After the tour, pilgrims were separated into small groups to discuss how it felt to go to the prison camp. Emotions ran high. For many descendants in the group, going to the camp was a way to confront their community and family’s history.

Throughout the pilgrimage, I heard that many survivors of camp avoided talking about their experience. For some survivors there is a sense of shame that they allowed someone to put them in these horrible conditions.

One man came on the pilgrimage with his father, who survived Minidoka. He said his father often refuses to talk about camp. Once they entered Minidoka, his father slowly began to tell stories his son had never heard before.

The son said coming to Minidoka gave him a chance to confront and see what his father endured. He says he wishes he came here with his dad sooner.

Others shared similar emotional stories and many in the group cried openly as they listened. The pilgrims agreed that coming to Minidoka to see the site with their own eyes was the first step toward healing.

Will wind turbines destroy Minidoka memories?

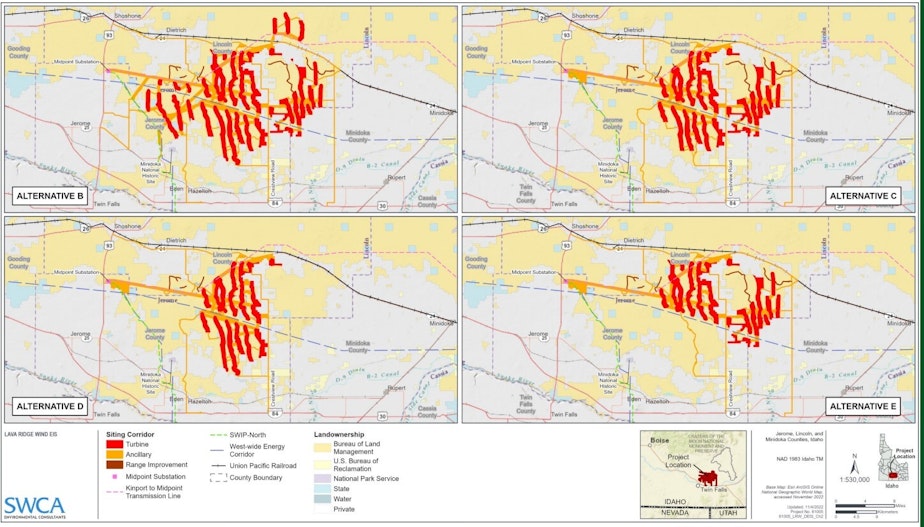

But, the experience of visiting the Minidoka prison camp could soon dramatically change. Magic Valley Energy is proposing a commercial scale wind energy project next to the Minidoka site called the Lava Ridge Wind Project.

According to the Bureau of Land Management, the proposed project could power up to 500,000 homes, with turbines up to 740 feet tall — taller than the Space Needle. The site could host more than 400 wind turbines. Some of them would fall within two miles of the Minidoka National Historic Site and inside the War Relocation Boundary. That means pilgrims and other visitors would see the turbines when they visit the remote site.

Gardner said that would ruin the experience.

“When I come to the pilgrimage, I feel the energy,” she said. “I see that I can feel the spirit that I've been here before, you know, and I just feel that for them to put up all those towers, it's going to destroy Minidoka.”

Gardner wants this historic site to be preserved. She wants future generations to be able to come to Minidoka so they can see the land and feel the energy, the same way she experienced it as a young girl.

Preserving the Minidoka story

Emily Yoshioka’s grandparents and great grandparents were held in Minidoka. She’s now a committee member of the group that organizes the annual pilgrimage.

She agreed with Gardner that the Lava Ridge project would dramatically change the experience of visiting the remote site.

“It will not be the same for the generations to come. It's something really scary to think about,” Yoshioka said. “But it's also a driving force. My desire to continue doing this work, being a part of the pilgrimage, and being a part of the Japanese American community.”

She said she understands that as a young person in the Japanese community, it is now her job to be the storykeeper. It’s also her duty to protect places like Minidoka from projects like Lava Ridge.

The Bureau of Land Management is currently reviewing more than 11,000 public comments about the Lava Ridge proposal. BLM spokesperson Heather Tiel-Nelson said the feedback from the Japanese American community is “pretty significant.”

She said the agency is trying to “mitigate impacts while at the same time trying to allow for Magic Valley energy to have a viable project.”

Preserving a place of painful memories

On the final morning of the pilgrimage, we returned to the Minidoka Historic site for a closing ceremony. There were speeches about the necessity of remembering what happened here and preserving this site about teaching future generations so that history doesn't repeat itself.

Pilgrims took “Emas” — wooden plaques shaped like houses — and wrote messages honoring and remembering loved ones who’d been imprisoned. They tied the messages onto display stands. Some elders helped younger children securely tie the Emas in place, while others hugged each other.

After the ceremony and goodbyes, I got into my car and drove out of the park. I passed the giant “Stop Lava Ridge” protest signs. In my rearview mirror, I saw the guard tower, the only thing rising above flat fields of golden grain.

Connecting past and present

A few days later, my mom and I researched Uncle Shosuke. I learned he was an activist for Japanese American rights.

He was one of the main authors of the first summary of the “Seattle Plan.” This plan was the initial step that led the U.S. government to issue an official apology regarding the camps and pay reparations of $20,000 per survivor.

Today, African Americans are using the plan as an example of how reparations are a possibility.

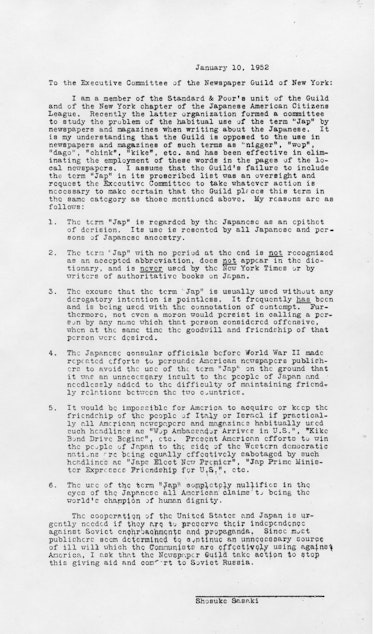

My mother also told me how much Uncle Shosuke hated the slur, “Jap.” She said she remembers him passionately talking about how terribly the media wrote anti-Japanese propaganda that dehumanized Japanese people.

During my research I learned that Uncle Shosuke wrote a letter to the Newspaper Guild of New York urging them to stop using the slur to describe Japanese people.

In an interview with Densho, an organization that preserves testimonies from survivors of WWII prison camps, Uncle Shosuke says the word was then put on the proscribed or forbidden list. The Guild thought it was such a great idea, they proposed prohibiting the use of the word in newspapers.

Uncle Shosuke said it was the first time a organization had “come out in open opposition to the use of the word ‘Jap.’”

It turns out my Uncle Shosuke, who was among thousands imprisoned against their will in a remote Idaho outpost, who endured sandstorms, shame, and humiliation, was brave enough and strong enough to speak out against the racism and discrimination that was so prevalent in his day.

It is because of him and his courage that I can work in public media today without that slur describing myself and my community.