Lapping Mount Rainier to map its withering ice

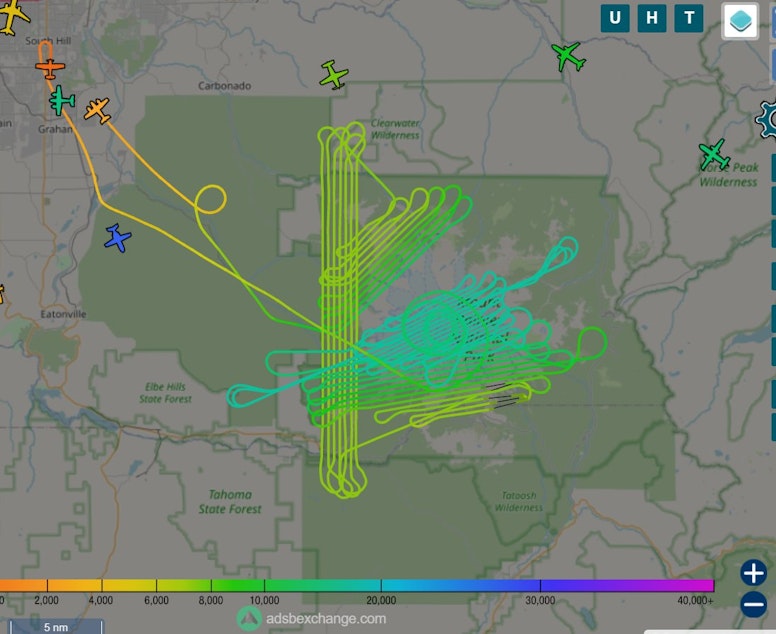

It might be the most bizarre flight path you’ll ever see.

A small plane took off from Pierce County Airport in Puyallup and headed up to Washington’s highest peak. It flew loops around the summit of Mount Rainier, then did dozens of laps, back and forth like a swimmer who changes lanes after reaching the end of the pool.

This was no sightseeing tour.

The specially outfitted plane, operated by Idaho-based Owyhee Air Research, was documenting the decline of the biggest collection of glaciers in the lower 48 states. For the first time in six years, Mount Rainier National Park is measuring its glaciers from the air.

Using a photogrammetry technique known as “structure from motion,” the plane took photo after photo at regular intervals to show the park’s glaciers and snowfields from multiple vantage points.

The technique lets researchers piece together a three-dimensional map of the park’s snow and ice and calculate how much the frozen world of Mount Rainier has withered.

“Every glacier in the park is retreating. Every glacier in the park is losing volume and losing ice," park geologist Scott Beason said. "They're not healthy, if you want to think of it that way.”

Sponsored

The 29 glaciers on Mount Rainier have been shrinking for many years as the local and global climates have warmed.

But tracking the retreat of something as big and deep as a glacier is not easy.

“Volume is extremely hard to measure,” Beason said.

He says it’s too soon to know what kind of impacts this summer of extreme heat has had, though he has seen anecdotal evidence.

Climbing guides had to abandon some routes to the summit this summer, including the popular Disappointment Cleaver route, because so much snow had melted away, exposing treacherous crevasses.

Sponsored

“I know there were more crevasses on the Muir Snowfield than any time I’ve been in the park,” Beason said. “That should probably tell us there’s been a lot more melt than usual.”

Beyond disrupting recreation, the retreating ice can cause flooding downstream and, over time, leave salmon without enough cool water to survive.

The national park uses other techniques to monitor its glaciers, including ground-penetrating radar and drilling to extract samples from the hidden depths.

Beason says the “structure from motion” flights are a relatively inexpensive way to study the park’s glaciers. He expects the data will also improve understanding of how the park’s ecosystems work beyond those covered in ice.

Three-dimensional mapping can also be done with drones, but drones are prohibited in all national parks.