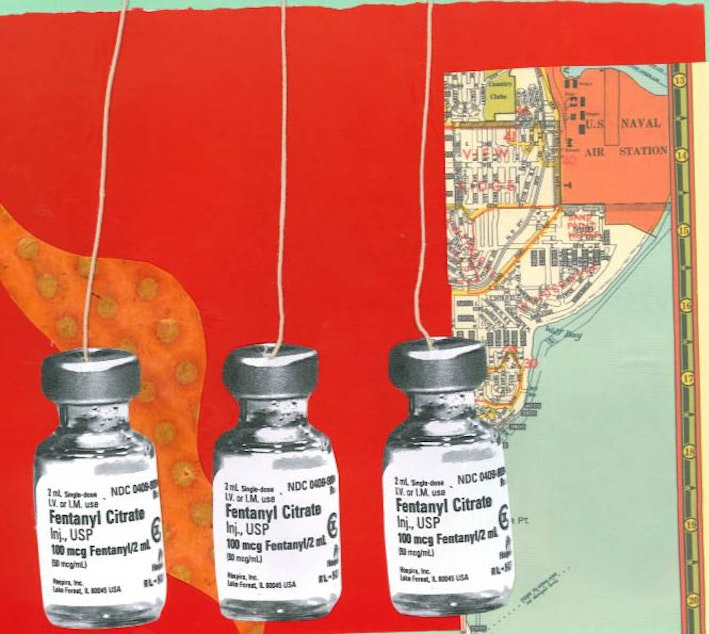

Massive shortage of pain meds affects Seattle hospitals

The supply room for drugs at Wenatchee LifeLine, a rural ambulance service, is bare. Morphine is scant. Bags of saline are precious.

LifeLine often transports critical patients from eastern Washington to the bigger hospitals in Seattle. The shortage of pain medications means some patients must grit their teeth in pain as they endure this hours-long ambulance ride.

The paramedics sit beside them, unable to offer relief.

“It’s a point of frustration for our crew members,” said Wayne Walker, president of LifeLine Ambulance, Inc. “They don’t have the tools they need to provide patient care.”

The problem only continues when the patients are delivered to the hospital. Drug shortages began about 15 years ago, when pharmaceutical companies began to consolidate, and stopping production of certain meds. But this current shortage is far worse, anesthesiologists say.

Sponsored

Doctors say they are resorting to drugs from the 1970s — more ketamine, for example, which is effective but can cause bad trips — and hoarding scarce drugs for extreme cases.

Two confirmed reasons for the shortage: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration dinged a Pfizer plant in Kansas for failing to meet standards, and Hurricane Maria pummeled Puerto Rico, where saline bags are made. Those are the reasons given — according to a statement from the FDA, pharma companies will also stop providing a drug for a while, without notice or explanation.

Providers are frustrated that the system is so beholden to these giant corporations, and that the feds are powerless to demand production for these vital drugs.

How the shortage has played out varies by hospital or agency — and Seattle has not been immune.

In southwest Washington, the issue became so acute that an anesthesiologist said she wouldn’t let loved ones get elective surgery.

Sponsored

At Children’s Hospital, a spokesperson said they’ve taken “steps to conserve our supply of these medications and ensure the appropriate medications are available for the patients who need them.”

Swedish Medical Center has a short supply of certain drugs, but it’s not critical, a spokeswoman said.

And UW Medical Center is doing relatively okay, although has limited drugs for c-section and epidurals.

At Virginia Mason, Dr. Julia Pollock, chief anesthesiologist, said her hospital is short on injectable opioids, typically administered to patients coming out of surgery. Anesthesiologists have adjusted by giving patients opioid pills before surgery.

She said she wouldn’t warn patients off elective surgery, however. “I would not be that dramatic,” she said.

Sponsored

But the shortage has meant that anesthesiologists everywhere have adjusted the formula for epidurals, which results in 10 to 12 patients a year with low blood pressure.

It’s not fatal, but those patients wind up in intensive care for monitoring. Surgeons don’t like that — it makes them look bad – and it scares patients, anesthesiologists say.

New York City has felt the pinch as well, said Dr. Ruth Landau, director of obstetric anesthesiology at Columbia University. She said her hospital has been desperately short on bupivacaine, a drug used for epidurals in one form, and C-sections in another.

“There have been near misses, but we haven’t killed anyone,” Dr. Landau said. “Because we are good at what we do, we have been able to avoid disasters.”

Dr. Landau has rationed the bupivacaine formulation used for c-sections, providing the rapid-onset drug in emergency situations only. Other moms get a form of bupivacaine that takes a little longer to take effect.

Sponsored

Dr. Landau is hoping that anesthesiologists elsewhere in the U.S. are not putting mothers under general anesthesia for emergency c-sections, because bupivacaine isn’t available.

“It’s a true risk,” she said. “We’ve perfected our ability to provide safe anesthesia, with less and less women getting general anesthesia. Now, just because we’re missing the right drug, we may be taking that risk.”

Dr. Landau and other anesthesiologists likened their situation to cooking without the proper ingredients: “It’s as if I told you, ‘bake brownies,’ and the sugar, chocolate and eggs that you never thought ran out, run out, and people are expecting you to bake the same brownies with the same quality. That’s how I feel.”

Meanwhile, providers say they’re frustrated with big pharma.

At LifeLine Wenatchee, Walker said suppliers are out of drugs, and he doesn’t know why. “I can’t find anyone who will give me an answer,” he said.

Sponsored

He finds it suspicious that a supplier might say they’re out, then point him to another supplier, one he hasn’t heard of. That company may have what he needs, but at many times the cost.

Anesthesiologists had similar questions for the drug industry.

Dr. Pollock of Virginia Mason said drug shortages have been a reality for 15 years. Even drugs that shouldn’t be expensive, because the research and development costs are paid off, are pricier, she said. She noted the EpiPen, for people with severe allergies.

“Suddenly drugs we had been using for 30 years weren’t available anymore,” Dr. Pollock said. “These are very important for anesthesia and also affect oncology drugs. We had to come up with a systematic way of dealing with this.”

From New York, Dr. Landau said, “It sounded like a political story of something really fishy.”

She asks herself whether anesthesiologists should have called more attention to the problem when it began earlier this year.

“We haven’t wanted to make a big deal out of it – part of it is we don’t want our patients to worry, we don’t want to create a frenzy.”

She also wondered if anyone would care.

“It’s just anesthesia,” she said. “It’s also just pregnant women having babies, which people care about even less.”

The FDA said intravenous opioid shortages will persist through 2019. Dr. Landau said she doesn’t know when bupivacaine will be available again in a reliable fashion.

“My hospital has recently received some supplies of bupivacaine – but we are not sure whether this is a random delivery,” she said. “We don’t know whether we can say things are back to normal.”