My Dad's Descent Into Terrifying Madness

Nando Ferahaha was a real man.

Nando was 48 and newly slim, with a shaved head and a septum pierced with a ring, like a bull. He said he was an amateur body builder.

Nando said he was an active member in our metropolitan area’s search and rescue team. He had $10,000 of new REI gear to prove it.

Then Nando’s enthusiasm turned to paranoia. Nando snapped.

Nando, a registered gun owner, sold his Glock and Beretta.

Sponsored

Nando then purchased a deadly arsenal of knives, hatchets and spears.

Nando fortified a blue-tarped lean-to, where he lived, with serrated hunting knives, switch blades and a machete. Nando slept with a hatchet under his pillow.

I’d see him for a fleeting moment, usually on his way to shower. Wild-eyed, he seemed to recognize me as an anathema.

But most of the time he looked through me, like I was a wisp of smoke remaining after a long-ended party.

Nando Ferahaha was my father.

Sponsored

He built his lean-to in our family home’s backyard.

And I believed Nando was going to kill my mother, my sister and me. We started finding nasty-looking knives around the house. His beyond-erratic behavior might have led to one slipping from his pocket, I thought. Or maybe he put them there, a razor-sharp calling card reminding us of his power.

On the stairs. In my bathroom. In the middle of the floor. Stabbed into the lawn.

I was 18, going to college, and terrified I’d be killed, alone in the basement, just feet away from the backyard door.

For weeks or months, I can’t recall, I slept in my mother’s bed, taking the place my father once occupied.

Sponsored

Curled up like a child in my mother’s bed, I figured he could get us all in one fell swoop.

None of us would have to die alone, go to Heaven alone, powerless from above, screaming as Nando, one by one, snuffed out the people who loved him and feared him the most.

My dad wasn’t always Nando.

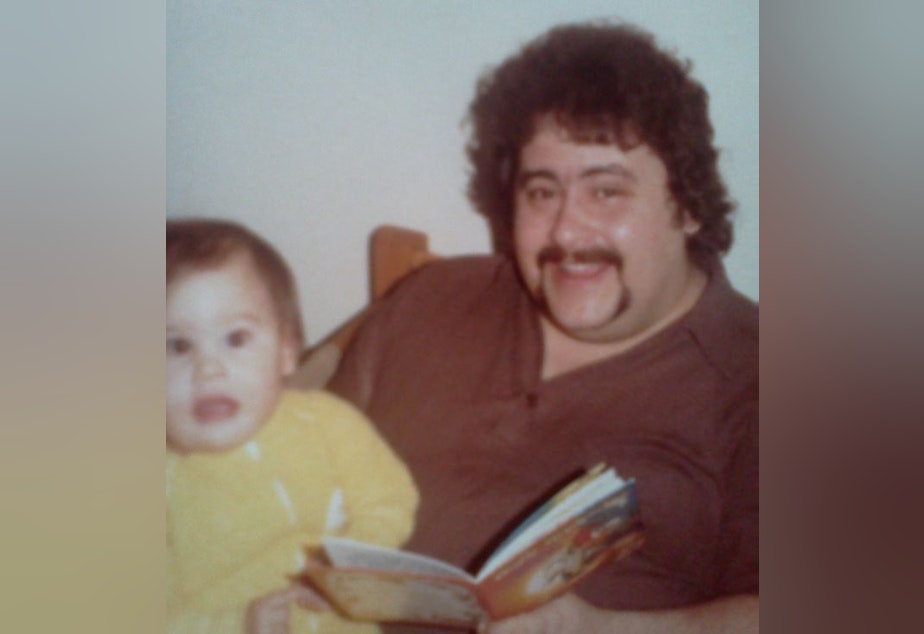

For most of my life, he was David, my dad.

One of my first memories is of him cooking in the kitchen — he loved concocting often delicious and sometimes inedible dishes — while singing Tony Bennett’s “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” in a funny, affected vibrato.

Sponsored

Intelligent beyond belief and possessing a fabulous sense of humor, he lived mostly inside his head. Usually he was on the couch, tuned in to the television, escaping whatever thoughts his synapses fired at him.

He didn’t have many friends. He never seemed to hold down a job for long.

For brief flashes of time, his charismatic personality shined like the sun, witty and hilarious, warming my family with this wonderful feeling of happiness. But these sun breaks were fleeting and rare, quickly clouded over by a morose turn inward.

Our one steady source of income came from my mom, who worked part-time as a hair stylist.

Dad loved the TV show M*A*S*H, and in the 1980s followed through with his dream to become a registered nurse. Ceaseless in his pursuit, he worked the night shift at a local 7-Eleven and went to class during the day.

Sponsored

We were so proud, watching him as he graduated with honors at the head of his class.

I was in elementary school when he landed a great job as a nurse at Harborview Medical Center. We moved from our noise-riddled rambler beneath Sea-Tac runway’s flight path to a mid-century modern home on a quiet hill near the water.

With a steady, substantial income and two parents who loved their careers, things at home should have been OK.

Of course, they weren’t.

Dad had a long-standing relationship, as Ozzy Osbourne sang, with The Demon Alcohol.

Until later in life when I began going to college parties, I thought it was normal for someone to drink four or five 40-ounce bottles of malt liquor a night. Rainier and Olde English were is favorites, and Snoop Dogg most definitely would have found a hearty drinking companion in Dad.

He was a brilliant nurse, and he was a tortured nurse.

When Dad would actually talk to me, he’d tell gross but amusing stories about a patient’s phlegm ejecting from their lungs only to dangle precariously from the hospital room ceiling. But sometimes the stories weren’t funny at all.

One I remember most was about a prostitute named Bunny, found nearly dead in a Dumpster with her neck sliced ear-to-ear. She wasn’t much older than me. He couldn’t save her. Bunny died.

To bury the pain, he added vodka to his daily diet of beer.

He’d always been prone to frightening outbursts of anger, but bottom-shelf vodka turned his emotional dynamite into nitroglycerine, ready to explode at any moment.

During these times, he’d take on a hushed, chilling tone as he calmly confided in me that I reminded him of himself. That he never wanted kids. That he especially didn’t want girls.

I knew that wasn’t true, but even now those moments were far more painful than when he’d grab me, shake me, poke me in the sternum until I wept or kick me over and over as I curled up in a ball to protect myself.

Dad had issues.

When vodka and beer weren’t enough, he turned to pills.

I was a sophomore in high school when he was fired after being caught stealing his patients’ opiates.

This former charge nurse at the state’s premier intensive care burn unit was now left to his own devices. Our family teetered on the edge of a financial and emotional breakdown.

He vowed to get clean.

Taking a job as a salesman at his brother’s carpet-selling store, things began to look up.

He was happy, outgoing. Connecting with us like he’d never done before, we believed he was sober and delighted in what it felt like to not walk on eggshells.

Taking my sister and me to Mariners baseball games, we finally began to get to know Dad. He smoked Kool cigarettes, always had a roll of fruit-flavored Certs and was touched to the point of tears when listening to his favorite artist, Roy Orbison.

The first indication my new Dad was coming unraveled was a new set of business cards.

He’d had 500 of them printed with the name “David David.”

“David, why?” my mom asked him, her voice pleading for a reasonable explanation.

“It’s catchy!” he enthused, “customers will remember me!”

Customers DID remember him, but for another reason.

While out measuring carpet jobs, he’d often “use the bathroom” to search medicine cabinets for prescriptions. He knew his pharmaceuticals, and stole whatever medications he thought might do the trick.

After a customer complained, Dad was fired. Again.

My mom had endured 27 years of Dad’s ups and downs, and couldn’t take any more.

By this time, I’d graduated high school and was beginning my first quarter at a local community college.

Our parents’ marriages contains within them a private space known only to each other. I have no idea what my mom had seen in those nearly three decades of matrimony, but she’d stuck it out far longer than I could have.

I understood this and supported her decision to divorce him.

Then Dad cracked.

From early on, I knew his brain was built differently. Nature or nurture? I don’t know. Probably both.

His spiral into madness began with the appearance of Nando Ferahaha, a name my father began calling himself.

At first, this Nando was the gregarious, outgoing, smart-as-a-whip and funny as hell Dad I’d seen previously only in flashes.

Then Nando turned dark, and I began living every day wondering if it was my last.

I confided in a friend, so he’d know what to tell the authorities if we were found dead.

Finally, Nando moved out of the house.

A week later, he called sobbing to say he’d just seen a doctor.

He had a brain tumor. It was pressing on a critical part of his brain and was the source of his irrational and scary behavior.

He had six weeks to live, he said. He was sorry, for everything.

We were devastated. Of course it was a brain tumor! It only makes sense!

During the phone call, Nando told us the name of this well-respected doctor.

As much as I loved my Dad, I needed to be convinced of his diagnosis and went to find this doctor.

But no such doctor existed.

Dad was crazy.

The following is what happened over a span of days, weeks and years. It’s a jumble of memories, because trauma often seals in vivid details without a date stamp.

In his new apartment, Nando was writing a suicide note, gun at his side, with his music turned way up.

It was the middle of the night, and another tenant called to report this disturbance.

Police found him, pen and pistol at hand, and had him involuntarily committed at a local hospital.

When the nurses called, I went to see him for the first time in weeks.

His nose was broken and bloodied.

“What happened?” I asked.

“I was doing one-handed push-ups as part of my training and hit my face on the ground,” he said, as if this was completely rational. “Yeah, they’ve got me doing the thorazine shuffle. I’m a little slow to react now.”

Stepping out to speak to the nurses, they told me Dad had bipolar disorder, and was in the throes of a quick-cycling mania-to-depressed state of mind.

Discharged 72 hours later, he moved in with a half-sister.

Like many people living with mental illness, the meds made him feel better. And since he felt better, he didn’t need to take them anymore. After all, he was once a well-respected nurse. He was smart enough to overcome whatever his brain threw his way.

With that, he began self-medicating again. Booze, pills, maybe even illegal drugs.

I didn’t see him for a long time, maybe a year. I was focused on going school full-time, earning my Associate’s and Bachelor’s degrees.

Then I got a birthday card from him in the mail.

“Dear daughter -

I hope this card and note find you to be well. [Your sister] tells me of the wonderful things you’re accomplishing in school, the radio and the newspaper stuff. I am so proud and happy for you. What a glorious time to be alive with your whole life ahead of you!! I hope you take some time to party hearty.

I know how busy you must be with school and all but it would be wonderful to see or hear from you. Nothing heavy-duty emotionally … chit-chat … you set the pace.

Needless to say, I miss you greatly.

Well, continue to do well. You’re going to accomplish great things.

I love you baby,

Dad”

I don’t know if it’s his beautiful block handwriting or the words he wrote that still bring me to tears.

I missed him, too. I wanted my Dad back.

But the prospect of seeing him was terrifying. I couldn’t do it sober.

Coming off a night of a rave-fueled ecstasy binge, I drove to his apartment.

Once inside, I saw my Dad like I’d never seen him before. Diagnosed with type II diabetes 20 years earlier, it was clear he wasn’t managing it at all.

He was blinded by glaucoma, his brown eyes now gray.

He wore gloves, because the feeling in his hands was fleeting and, when he had sensation, excruciatingly painful.

He couldn’t walk, because his feet were numb.

The man who in better years only left the house if he had showered, shaved and wearing Givenchy cologne now stank. He’d fallen in the shower and remained helpless until his half-sister came home, he said, and now was afraid to bathe at all.

Nando Ferahaha and the angry side of my dad I once feared were now gone.

Left in their wake was a weak man, tame as a kitten, sedated by drugs and disease.

Our visit was brief, and filled me with shame for not having helped him sooner, and sorrow because I knew there wasn’t anything I could do.

Sometime afterwards, the hospital where he once worked — indeed, a nurse from very same Burn Intensive Care Unit where he was fired – called and said to come to down right away.

Dad was dying.

Now divorced from my father, my mom couldn’t endure anymore and left his care to my sister and me.

So we went to see him.

Being taken to a conference room with the hospital chaplain and a doctor usually isn’t a good thing.

Dad, who hadn’t bathed in months, had a sore on his leg, which became infected, the doctor explained.

Because of his progressive diabetes and limited blood flow, the infection developed into necrotizing faciitis, a flesh-eating bacteria.

Doctors performed surgery for hours, but the infection had gone septic — it was in his blood.

They urged us to see him, to say goodbye.

His hospital room stank like rotting flesh and unwashed man. Long, greasy hair scraggled from his head. A ventilator tube snaked out of a patchy Grizzly Adams-esque beard. Toenails, thick and yellow, were talons on his purple feet.

It was ugly.

But, oh, he was tenacious even in his post-surgical coma. He lived.

Nine months Dad spent in the hospital, recovering from skin grafts and operations to heal the giant divot that extended from stomach to thigh.

He was released to a nursing home, where he spent the last few years of his life.

My sister and I were vested with power of attorney over our ailing father, but we were both students in our early 20s and couldn’t afford any place other than this institutional, sad state-funded nursing home for the indigent.

She lived nearby and visited him often, reading him Michael Crichton novels or talking about the Mariners. My younger sister bore the brunt of Dad’s care, and I’ll never forgive myself for that.

I lived a couple of hours away. This was my scapegoat for not seeing him.

The truth was it was too raw, too painful. I couldn’t handle seeing my Dad, who once wore beautiful suits, in a sweatshirt with a silk-screened wolf howling at the moon. He would’ve died of embarrassment alone, had he been able see what he was wearing.

The few times I did visit, I found him in a wheelchair, hooked up to oxygen, so happy to see me.

“Hey,” he’d whisper. “Let’s get out of here and smoke a doob!”

I’d laugh, tell him I didn’t bring any pot.

So we’d settle for a cigarette in the nursing home’s smoking room.

He’d suffered several strokes and lost all his teeth, leaving him to speak in a language he jovially referred to as “Strokenese.”

I knew he was dying. For most of his life, I’d felt like he never wanted to live. Now was his chance to give in.

On my last visit, I said everything I’d ever wanted to say.

I forgave him for the way he treated me, and I meant it.

I told him that I loved him.

I told him he’d be in my heart and that I’d carry his spirit with me as I walked down the aisle to get married.

He apologized for everything he’d put me through. He said he wished he could’ve been a better father.

Through tears, I asked him if he was afraid to die.

With a toothless grin, he thought a moment.

“I just hope when I reach the pearly gates Saint Peter doesn’t make me spell chrysanthemum to get in,” he said.

He died a short time later of renal failure. He was 52.

Only with his death could my healing begin.

As much as I love him, I never want to be like him.

Within us both was planted the seed of mental illness (mine to a lesser degree, but a mental illness all the same).

Part of my healing is knowing I have the power to stop my seed’s germination, to pharmaceutically stunt it from take root and developing into something that could brand the lives of everyone who loves me with fear, sorrow and sometimes hate.

This essay was first published on Lisa Southworth’s blog, Taming Flamingos. She lives in White Center.

The Seattle Story Project: First-person reflections published at KUOW.org through December. These are essays, stories told on stage, photos and zines. To submit a story - or note one you've seen that deserves more notice - contact Isolde Raftery at iraftery@kuow.org or 206-616-2035.