Jumping slugs: the tiny slimy acrobats of Northwest forests

The Pacific Northwest is home to a group of rare species you’ve probably never heard of. Their name alone might horrify or delight you: jumping slugs.

Environmentalists and the federal government are clashing over a species whose populations seem to be declining along with its habitat on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula.

It’s not a salmon or a spotted owl or even a salamander.

It’s a slug, and it jumps, sort of.

Unless you’re a malacologist, as mollusk experts are called, you’re unlikely to have seen or even heard of this half-inch-long creature: the Burrington jumping slug.

Sponsored

The denizen of fallen maple and alder leaves can only be found from Canada's Vancouver Island to the Oregon Coast Range.

Though its fans say the tiny mollusk is charismatic up close, it is camouflaged and furtive enough to evade detection by casual interlopers in its mossy rainforest habitat.

Most slugs are known for slowly and slimily sliding along the ground, but at least a half-dozen species in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho are called jumping slugs for their habit of writhing and flopping like a fish out of water. Biologists believe it’s a defense mechanism.

The slugs don’t get big air, but they might fall off a branch or leaf they’re on and break free of their own slime trail to throw a hungry predator off the scent.

“Yes, they jump,” said biologist Michael Lucid of Selkirk Wildlife Science in Sandpoint, Idaho. “But they don't jump as you might imagine.”

Sponsored

“Yeahhhhh,” retired biologist Bill Leonard of Olympia said hesitantly. “More like somersaulting or something than jumping.”

Above, a dromedary jumping slug, a close relative of the Burrington, thrashes on Vancouver Island.

“It's kind of that corkscrew-tight coiling and uncoiling that causes them to lunge or tumble,” Leonard said.

He saw his first jumping slug on the Olympic Peninsula in 1982.

“I was working doing spotted owl monitoring up there and saw these crazy slugs,” Leonard said.

Like spotted owls, the jumping slugs are considered a kind of indicator species for Northwest forests.

Jumping slugs are sometimes called semi-slugs: they’re halfway between snails and slugs, carrying a sort of half-shell around inside a hump on their backs.

Sponsored

Slugs are snails whose ancestors dispensed with all or most of their shells at some point in their evolution.

If you’ve ever pondered slugs, there’s a good chance you think of them as slimy pests that can make gardening an exercise in frustration. Mollusk experts say the garden and crop destroyers are almost exclusively European species that somehow hitched a ride across the Atlantic.

There are at least six species of jumping slugs in the Pacific Northwest.

“These are integral residents of our Northwest forests,” Leonard said. “They don't occur anywhere else in the world.”

The Burrington jumping slug glides through wet forests from the Oregon coast to Vancouver Island, where biologist Kristiina Ovaska studies a variety of small creatures. (“All things slimy and scaly,” she said.)

Other people go birdwatching. Ovaska goes slugwatching.

“You have to look very carefully, like one leaf at a time, and you can find them on the forest floor,” she said.

The Burrington jumping slug might never be a Northwest icon like salmon or orcas, but Ovaska says if you get close enough, it has a certain charisma.

It has a multicolored hump like a bedazzled little backpack. Its eyes are on the end of cute little eye stalks.

“We have tail droppers and jumping slugs, and we have these really cool native species in our forest that most people know very little about,” Ovaska said.

Jumping slugs might not have many fans, but they do have ardent fans.

In England, there’s even an Ugly Animal Preservation Society that speaks up for Northwest jumping slugs, among other oddball species.

“A slug, with a hump on its back, and it can jump, where’s its Disney movie?” a society video asks. “We’ve got the Hunchback of Notre Dame. Where’s the Dromedary Jumping Slug and the Princess?”

(In a contest to choose the Ugly Animal Preservation Society’s mascot, voters picked the blobfish over the Dromedary jumping slug, a close relative of the Burrington.)

Conservationists plan to sue the federal government to keep the Burrington from going extinct.

In November, the Center for Biological Diversity gave the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service the required 60 days’ notice of its intent to sue the agency for not granting endangered-species protection to four species: the Burrington jumping slug, the rubber boa of southern California, the Black Creek crayfish of Florida and a Utah fish called the Virgin River spinedace.

The center also gave notice it would sue the agency for delaying protections for another six species, including the Siuslaw hairy-necked tiger beetle of Oregon and Washington.

The fish and wildlife service found that the jumping slug was in trouble in much of its range, especially along Hood Canal, Willapa Bay, and on Vancouver Island.

When their habitat is cleared, the slugs can’t glide or jump away fast enough to find a suitably wet and shady place to live.

“Burrington Jumping slug will continue to decline in levels of resiliency, redundancy, and representation within 20 to 50 years,” the agency concluded.

Still, the agency said the species had “moderate” resilience and did not warrant new measures to protect its habitat, prompting the lawsuit.

“We have to do a better job protecting our forests and protecting old forests,” said Noah Greenwald with the Center for Biological Diversity, the group suing to protect the slug as an endangered species.

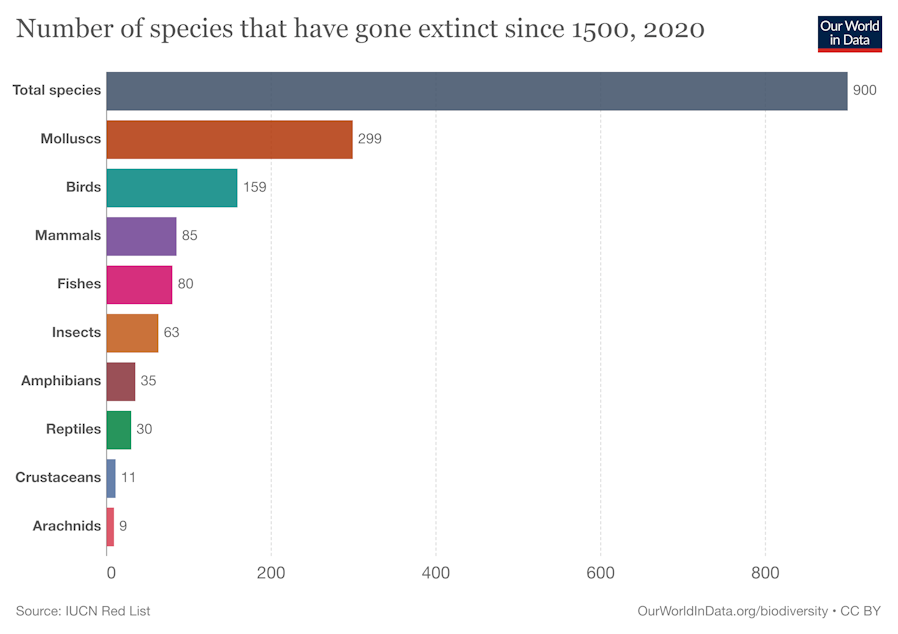

As far as scientists have been able to document, more mollusks have gone extinct in modern times than any other type of animal. The few people who study these overlooked animals think they deserve more respect, especially given all the work they do for us.

“Decomposition is not as sexy as pollination,” Lucid said. “But it's a super essential ecosystem service nevertheless.”

“Imagine a world without decomposers,” he said. “Imagine the leaf litter that would build up on the forest floor, and all of the fuel that would fuel these fires that are already getting bad. So the species group is really important to humans.”

Nearly 20 years ago, the U.S. Forest Service said the Burrington jumping slug depends on old-growth forests. Lucid says it can thrive in younger forests too, as long as loggers leave microhabitats with shade and woody debris the slugs can stay cool under–and as long as our changing climate doesn’t dry out the wet places the slug calls home.

“It definitely is sensitive to warming temperatures,” Greenwald said.

“The ecosystems that we all depend on and that are made up of species are beginning to unravel across the world,” he said. “The Burrington jumping slug might seem like a small species, but it's one of the ones that's caught up in that.”

Extinction and our unraveling climate are ongoing tragedies, yet there’s also comedy about jumping slugs.

While some experts say jumping slugs don’t really jump, Tim Pearce, the mollusk curator at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History, says they can jump higher than the Empire State Building.

That’s because the Empire State Building can’t jump.

“I once told my friend I was going to the Olympics to see the jumping slugs,” Pearce said. “And she said, ‘I didn’t even know that was an Olympic event.’”

People who study these overlooked little creatures seem to develop a real fondness for them.

In Idaho, Michael Lucid and his wife, biologist Lacy Robinson, named a species of jumping slug they discovered in 2018 after their young daughter, Skade. They’d named her for the Norse goddess of winter, mountains, skiing, and bowhunting. Skade’s jumping-slug, their research found, lives in the coldest nooks and crannies of Idaho’s Coeur d’Alene Mountains and may be especially sensitive to climate change.

“These are species that need it cold, they need it wet, and anybody who lived through last summer in the Northwest knows that that is changing,” Lucid said.

Ovaska said another rare mollusk, the blue-gray tail dropper, seemed to have disappeared from the site she studies on Vancouver Island after this summer's drought and extreme heat.

Now Lucid and Robinson are hoping to find another new mollusk species to name after Skade’s little brother.

“Fair is fair,” Lucid said. “We’re going to get in trouble some day if we don't find another one for him.”

Lucid says he wants to make sure jumping slugs are still around when his kids are grown up.