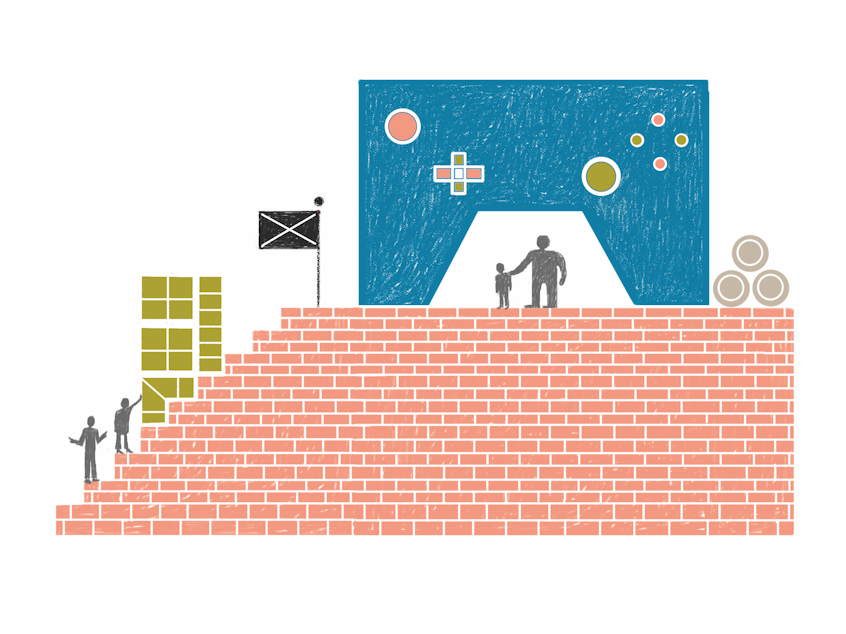

Right-Wing Hate Groups Are Recruiting Video Gamers

John, a father of two in Colorado, had no idea what his 15-year-old son had gotten into, until one night last year when John walked into his home office. We're not using his last name to protect his son's privacy.

John saw a large pile of papers facedown next to his printer. He turned them over and found a copy of a notorious neo-Nazi propaganda book. "It's 'the white culture's in trouble, we are under attack by Jews, blacks, every other minority.' It was scary. It was absolutely frightening to even see that in my house. I was shaking, like, 'What in the world is this and why is it in my house?' "

John confronted his son angrily.

"I was through the roof." And then, "I went back into my room. I was crying. I felt like a failure that a child that I had raised would be remotely interested in that sort of stuff."

Almost every teen plays video games — 97 percent of boys, according to the Pew Research Center, and 83 percent of girls.

Sponsored

Increasingly, these games are played online, with strangers. And experts say that while it's by no means common, online games — and the associated chat rooms, livestreams and other channels — have become one avenue for recruitment by right-wing extremist groups.

At the time, John's son liked playing first-person shooter games, like Counterstrike: Global Offensive. Games like these are multiplayer — you must form teams with friends or strangers. You can chat in the game, over voice or text, or in separate chat rooms. Some of these are hosted by sites like Discord that make it easy for anyone to create a private chat.

John knew his son was spending time playing video games and chatting either out loud or over text, but there were no obvious red flags.

"There wasn't anything obvious to me at first because it's common. This is the norm for kids. Instead of hanging out at the drive-in they're all online," he said.

Yet it's exactly this way, John says, that his son started hanging out with avowed white supremacists.

Sponsored

These people became his son's friends. They talked to him about problems he was having at school, and suggested some of his African-American classmates as scapegoats. They also keyed into his interest in history, especially military history, and in Nordic mythology. Above all, they offered him membership in a hierarchy: whites against others.

"He started to feel like he was in on something. He was now in the in crowd with these guys. It provided some structure and identity that he was searching for at the time."

John learned his son had been drawn into conversation with at least one group that the Southern Poverty Law Center calls a Nazi terrorist organization. He searched online for help and found a man named Christian Picciolini.

Picciolini runs the Free Radicals project, which he calls "a global prevention network for extremism." He's a reformed skinhead himself.

"Thirty years ago, when I was involved in the white supremacist movement, it was very much a face to face interaction," he says. "You know, you had to meet somebody to be recruited, or you had a pamphlet or a flyer put on your car."

Sponsored

But today, he says, it's much more common for extremists to initially reach out online. And that includes over kids' headsets during video games. Picciolini describes the process: "Well typically, they'll start out with dropping slurs about different races or religions and kind of test the waters ... Once they sense that they've got their hooks in them they ramp it up, and then they start sending propaganda, links to other sites, or they start talking about these old kind of racist anti-Semitic tropes."

That's also what Joan Donovan has seen. She is the media manipulation research lead at Data and Society, a research institute, and she has been following white supremacists online for years. She says they've been highly innovative in using new online spaces, like message boards in the '90s, for recruitment.

"I saw how these groups communicated and spread out to other spaces online with the intent of not telling people specifically that they were white supremacists, but they were really trying to figure out what young men were angry about and how they could leverage that to bring about a broad-based social movement."

And violent first-person shooter games, she says, are one place to find angry young men. She calls "gaming culture" "one of the spaces of recruitment that must be addressed."

Donovan says that recruitment, and even the planning of harassment campaigns, happens not only during in-game chat, but during livestreaming of game play on platforms like Twitch and YouTube.

Sponsored

For example, there's a feature on YouTube called Super Chat, where fans can offer cash tips while gamers are playing.

"People will donate 14 dollars and 88 cents, which is a reference to ... a white nationalist slogan, as well as 88, which is most commonly found in prison tattoos, for Heil Hitler," Donovan said.

Game-related Reddit threads and chat sites like Discord also host similar conversations. Last year, a nonprofit media collective called Unicorn Riot published chat logs from Discord in which known white supremacists planned aspects of the Charlottesville "Unite The Right" rally.

Video games are a hundred billion dollar industry.

What are companies' responsibilities to ensure that young people won't encounter hate groups? We reached out to several game and chat companies for comment. Riot Games noted in a statement that it relies on volunteers to moderate game-related chats. And Discord, the chatroom site, forwarded a statement from the Southern Poverty Law Center, praising it for recently banning several far-right extremist communities.

Sponsored

Greg Boyd, who represents video game companies for the law firm Frankfurt Kurnit, says "toxic" behavior including hate speech, to say nothing of recruitment, is a key industry concern and a frequent topic of conversation. "If they could find it all they would get rid of it ASAP."

But it's a daunting technical challenge. The three biggest video game platforms — Microsoft, PlayStation and Steam — host 48 million, 70 million and 130 million monthly active players respectively, Boyd says. "That's the populations of Spain, France and Russia. And then imagine that you're monitoring all of their text chat ... all of their voice chat, in literally every language, dialect, and subdialect spoken in the world."

In the absence of sufficient resources for moderation, most game platforms rely on players to monitor and report each other.

Picciolini compares the companies to landlords with disruptive tenants "disrupting or damaging the building or threatening the other tenants. You know, they would take action."

But, Picciolini says, ultimately unwinding the influence of these groups over young people takes love and acceptance. He counseled John to find out what his son's personal struggles were — he calls them "potholes." As John put it, "He's missing something, so find out what those [potholes] are and fill those with something positive and healthy, and that's the way to steer them out of all this."

It took time, but lately, John says, his son, now 16, seems to have left these ideas behind. He's playing fewer networked shooter games, and on his own, he has started attending church. [Copyright 2018 NPR]