Seattle Mountain Rescue celebrates first home base in North Bend

For 75 years, Seattle Mountain Rescue has relied on a constellation of volunteers and a mixed bag of resources to help lost hikers and injured adventurers. As King County has exponentially grown, the demand for Mountain Rescue services has too.

Now, for the first time, the nonprofit will have a base of operations in North Bend.

On a summer evening beneath Mount Si, Seattle Mountain Rescue (SMR) is getting ready to celebrate their 75th anniversary when a call comes in. A crew needs to head up to Mount Rainier to help with a search and rescue mission.

"It's really fun and exciting to have it all come together," says Garth Bruce, a volunteer with the rescue group for the last 30 years. "But of course, there's the chaos of the missions in-between."

Bruce's phone gives a constant ping as he darts between equipment trucks and a nearby barbeque. Since its inception in the 1940s, Seattle Mountain Rescue has never had a home base. That meant parking their two emergency trucks in different parking lots throughout North Bend. When a call came in for a rescue, volunteers were sent scrambling.

"We've had like over a hundred missions a year now, one every three days on average," Bruce said. "And it just was unobtainable to support that. So we had to kind of think, what's our next stage?"

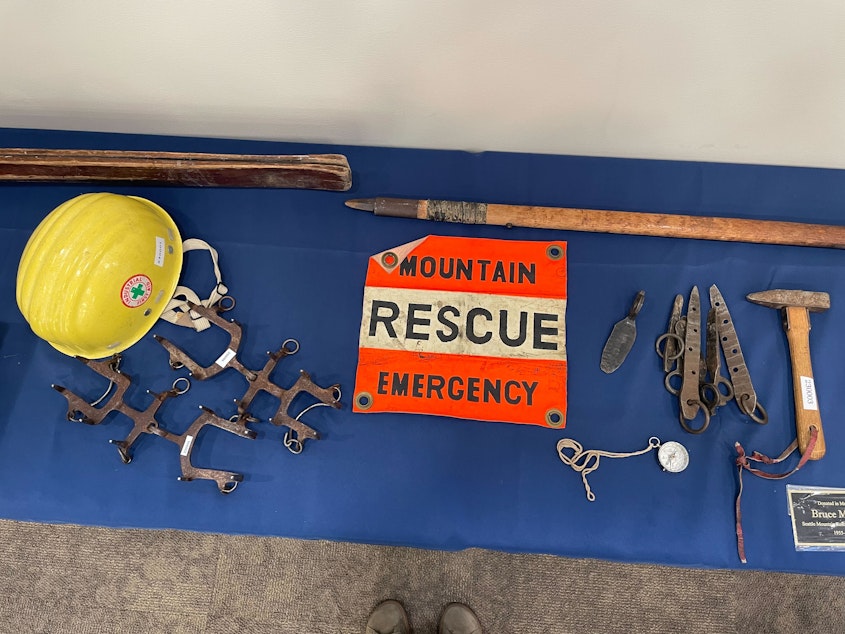

A lack of a main facility also meant the group's equipment was spread across different members — things like climbing ropes, emergency aid materials, insulating sleeping bags and satellite electronics.

Sponsored

"You get up there, you don't know what's going to happen, you don't know what you're going to need and it's always going to be raining and snowing and both at the same time," Bruce said.

There are nine mountain rescue organizations across the state, each designed for the fastest response times to regional rescues throughout the Cascade and Olympic mountains.

To celebrate the opening of their first ever operations center, former volunteers from across the country flew in to share the rescue missions that molded them and the outdoors community. The volunteers have converted their old blue rescue truck into a kind of makeshift studio to catalog the stories that have defined the last 75 years of mountain rescue.

Sponsored

A

l Errington originally moved from Minnesota to work at Boeing in the 1960s. He's has always been an avid outdoorsman, and mountain rescue sounded like a great way to spend more time in the wild. But in 1968, on his first mission, he quickly realized rescue was about more than just adrenaline.

"We got a call in the middle of the night. All calls come in the middle of the night. There's no daylight in mountain rescue," Errington said.

A woman was injured in Chelan County, which didn't have its own rescue unit 60 years ago. SMR quickly mobilized and drove out to Leavenworth.

"We didn't have cell phones. Gas stations are closed at night," Errington said. "And so, this is my first real rescue. And somebody hands you a body bag — all of a sudden it doesn't look like this is going to be a totally pleasure walk."

Sponsored

The rescue was for a woman who had tagged along with some rock-climbing friends, and while they were getting ready to climb on the crags, she sat on a ledge reading a book. When she turned around to grab something from her pack, she fell.

"I can picture it like yesterday," Errington said. "She took about a 30-foot fall down nearly vertical terrain and hit face first on another rock ledge, smashed into it, just rolled off that ledge, did it again down another slab, fell another two, three stories."

The rescuers applied emergency aid while formulating a plan to get the hiker off the mountain. Hiking her down the steep trail was out of the question — it would take too long, and she would bleed out. So, they called in a helicopter and made their way to a small tower of rocks nearby.

Normally they would attach something like a stretcher to a rope hanging from the helicopter, but they didn't have the winch or the room for that.

"Got up on top of this tower, which is about the size of a pool table on top, and the helicopter came in and hovers right next to us four feet from the wall, and the rotors are washing right over the top of us," Errington said.

Sponsored

They managed to get her into the helicopter and to the hospital, and Errington didn’t know what happened to the hiker. Months later, at an SMR meeting, the recovered hiker filed into the back, surprising the group.

"We just erupted off the chairs," Errington said. "Mountain Rescue owned my soul after that. And with all the excitement, the adventure of rescuing, I think it was a fair trade. I don't know if my soul was really worth it, but I'm accepting the trade. I got no complaints over it."

Errington kept up mountain rescue for decades after that. Boeing would even let him take one day a week to work a rescue mission, if it came in. He remembers those old days as full of helicopter rides. A lot of pilots were coming back from Vietnam and looking for ways to fly.

But alongside the adrenaline are numerous close calls. It can be hard to fathom why someone would volunteer to put themselves in such high stakes situations. Washingtonians have a love of hiking, but going out with friends on the weekend is a far cry from taking on the responsibility of saving someone’s life out in the mountains.

But when rescue workers are performing as a team, they’re able to handle difficult moments with clarity.

Sponsored

"You get five people sharing something and it's pretty bearable," Errington said. "You can pick up a pretty heavy load of five people emotionally. I think that's the biggest change over time."

Garth Bruce said that’s a skill volunteers have to develop, just like rigging, or emergency aid.

"It can be stressful. There's no doubt," Bruce said. "A lot of times we get into situations where we have to make difficult calls," he said. "And so, we do and have different methods to assess that risk and we check in with each other all the time, right? 'Hey, how you feeling about this?'"

Finding ways to decompress after a mission is something the organization has wanted for a while, and it’s one major benefits of the new home base in North Bend. The base includes three specially trained emotional distress dogs to fill out the crew.

"We do these hard multi-day rescues, it would just be whipped and then everybody would just leave," Bruce said. "A lot of these things can be really tough, and we wanted the members to have time to process it and think about it go over things that went really well, things that didn't go well, and maybe if there was some trauma, we dealt with that."

Since many of the older members first started their rescues in the 1960s, the number of missions by Seattle Mountain Rescue has ballooned. The group has also grown to about 70 volunteers, and missions are typically made up of a dozen people.

Volunteers say rescuing has gotten better now that the organization has grown. There are fewer daring helicopter rides, but gear is stronger and more lightweight, and the addition of cell phones and other technologies has made rescues more efficient. The kind of accidents people get in haven't changed much in the last 75 years, just how often people are getting into them.

So, why are these organizations still run by volunteers? With a world class wilderness next door, it isn't a stretch to wonder if mountain rescue could be an official part of our local emergency response. From Bruce's point of view, it would be hard to find the right people any other way than voluntary sign-up.

"You know what's doable, what's not doable," he said. "All of that really ties and makes this a huge success as far as rescue. You just can't put that together in an organization. That's not something you can train or teach. That's just something that some people are called to."

As summer hiking season kicks into gear, there are a few things to keep in mind to avoid engaging Seattle Mountain Rescue and staying alive if you do run into trouble:

- Pack essentials like a map, compass, emergency kit, and plenty of water.

- Check the weather and have a plan for when and where you're headed, and for extended periods of time, tell a friend or family member.

- And if you're ever lost or in need of a rescue, you can try calling 911 -- even if you don't have service, pings from nearby cell towers can communicate your location.