Seattle shipwreck enthusiasts find possible site of the deadliest wreck in PNW history

The S.S. Pacific was packed full of passengers in 1875. It was charting the first steamship voyage from Seattle to San Francisco, before Washington had even achieved statehood. But after a collision with a sailing vessel called The Orpheus, the Pacific and its cargo were lost.

Now after decades of searching, two local researchers think they've found it.

The wreck has also fired up imaginations because of rumors that it was carrying millions of dollars' worth of gold. But for researchers Jeff Hummel and Matt McCauley, the story behind the Pacific is what captured their imaginations back in the 1980s.

The two met at high school on Mercer Island in 1979. Rumor had it that Hummel knew about a sunken plane that his late father had seen crash from his job at the Renton Boeing plant. McCauley had just received scuba certification, and together, they devised a plan to pull the plane up from the seafloor.

The two friends knew the Navy had ownership over crash sites, but they figured out that this particular plane was intentionally discarded. In preparation, they wrote to the Navy to get approval, who responded that they were unaware of any protocols around intentionally discarded planes.

"We got a letter from the Pentagon," Hummel recalled. "And we thought yeah, that was pretty good."

To McCauley and Hummel, that was a green light. Using old air hoses they gathered from gas stations and connected lift balloons, they could pump air down to the lakebed and progressively raise the plane.

Sponsored

But the next issue arose when they needed to pull the plane out of the water. By borrowing a truck used to drop telephone poles, along with a wide load permit from the Washington Department of Transportation, they pulled the wreck to a local hangar. But short on money, the plane ended up in McCauley's driveway, and become a bit of a roadside attraction.

"It was a great conversation piece, " McCauley said. "It made it really easy to find my house for parties."

That's when a surprise came. Despite their earlier diligence, the Navy was indeed interested in keeping the plane under their custody. At 19 years old, McCauley remembers standing in his doorway as a man in a green polyester suit handed him a stack of papers. The two were being sued by the Navy.

Sponsored

"The people in the Seattle area were totally behind us," McCauley said. "This was like a governmental Goliath against two Davids."

The court case lasted several years, eventually siding in favor of McCauley and Hummel. They then sold the wreck to Northwest Airlines, and for the last 20 years, the plane is gradually being restored. Hummel expects the aircraft to take to Seattle skies once again in the next year and a half.

Together, the crew would eventually find and raise four more planes from the bottom of Lake Washington, and in an agreement with the Navy, they split a portion of their earnings. The first plane ended up being a specially modified Curtiss Helldiver, the second of its kind to ever be restored.

Afterward, the two went on with their lives in different directions. But McCauley owned a book on northwest marine history, and one particular fiasco — that of the S.S. Pacific — captured their imagination and newfound knack for spotting sunken treasures.

There was the story of Jefferson Davis Howell, the captain of the ship and brother-in-law of Confederate president Jefferson Davis (Seattle's Howell Street still bears his name). Then there was the significance of coal mines at Newcastle, which were helping the small town of Seattle stand out from nascent Olympia, along with a short-lived gold rush.

Sponsored

Estimates from accounts at the time say that around 300 passengers were aboard the Pacific, but the ship was so crowded the figure could be as high as 500. After scraping the side of The Orpheus — the captain of which may have confused the lights atop The Pacific with the Neah Bay lighthouse — a hole opened in the boat, and the ship began to sink.

"You had two days of storm that rolled through and pounded the area," McCauley said. "It was one of these once-in-a-century kind of deals."

In the end, only two passengers survived, named Henly and Jelly.

It's thanks to those survivors that marine researchers have known the general location of where the wreck could be. Hummel initially did some sonar scans of the area in 1993, to no avail. That's when he began speaking with local fishermen, who would turn up random items from the seafloor in their nets.

One fisherman in particular had pulled up a wheelbarrow's worth of coal — an anomaly for the area. Hummel tracked down a piece and had it tested, finding that it likely came from the northwest, and potentially, the Pacific. He then saw the logbook from that same fisherman, which gave him coordinates for where the coal was found.

Sponsored

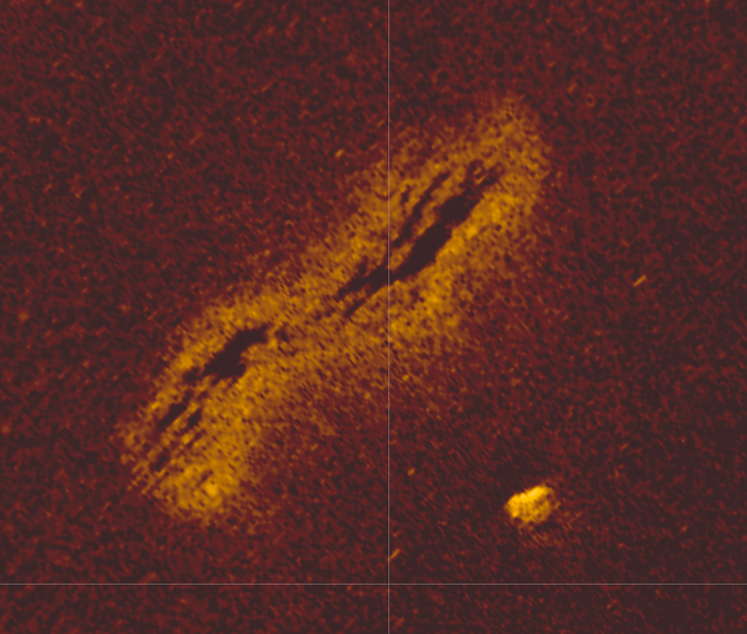

After a handful of expeditions, during which Hummel explored the crags and canyons of the area, the crew found a wreck 40 miles off the Washington coast, and numerous indicators point to the S.S. Pacific.

Hummel's company, Rockfish Incorporated, was granted exclusive salvage rights by a judge this month. The full details of the wreck aren't yet available, but McCauley and Hummel say the site is in remarkable condition.

Sponsored

Rockfish currently has an agreement with the Northwest Shipwreck Alliance, which Hummel is a board member of and McCauley presides over, to turn over personal effects and artifacts to local museums like the Museum of History and Industry. If there are any members of the public or businesses who may have ownership rights over property on the wreck, they can also come forward and claim portions of the wreck.

For the two long-time friends, they're hoping to create a maritime museum in Seattle, which could house artifacts from The Pacific along with other significant shipwrecks in the region.

"So we have found this ship off of the coast, artifacts that obviously related to the ship," said Hummel. "But then the story also relates heavily to Seattle, and we're going to bring all of that together."

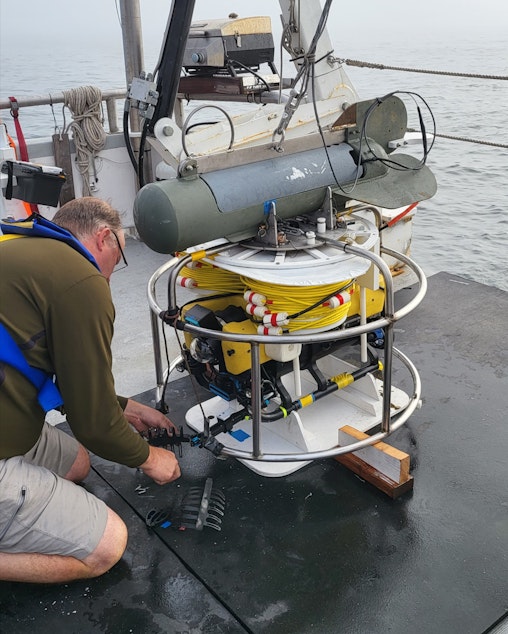

The find comes 40 years after the two began pulling planes from Lake Washington. McCauley notes Hummel's drive to build anything and everything to accomplish their expeditions, all the way from discarded air hoses to his recent remote operated vehicles.

"He's always been like that," he said. "It's pretty entertaining."

Listen to the full audio story by clicking the "play" button above.