Should parents be able to weigh in on teens' mental health treatment?

In Washington state, kids who are 13 and older can access mental health treatment on their own. They can refuse treatment, too.

Parents have lobbied for decades to change the law. This year, they are making another run at it, with new allies in their corner.

I

t wasn't supposed to be this way.

In 1985, Washington state lawmakers were considering a mental health bill for kids.

The bill included a provision that teens age 13 and older be allowed to consent for their own mental health care.

"It was looking at those kids whose parents maybe wouldn’t support them in getting treatment," said Kathy Brewer, an administrator at Seattle Children's, and also a therapist.

Sponsored

At the time, the provision wasn't all that controversial. It passed the Legislature overwhelmingly.

But in the decades since, tearful parents have periodically testified that the law makes it difficult for them to help their mentally ill teens.

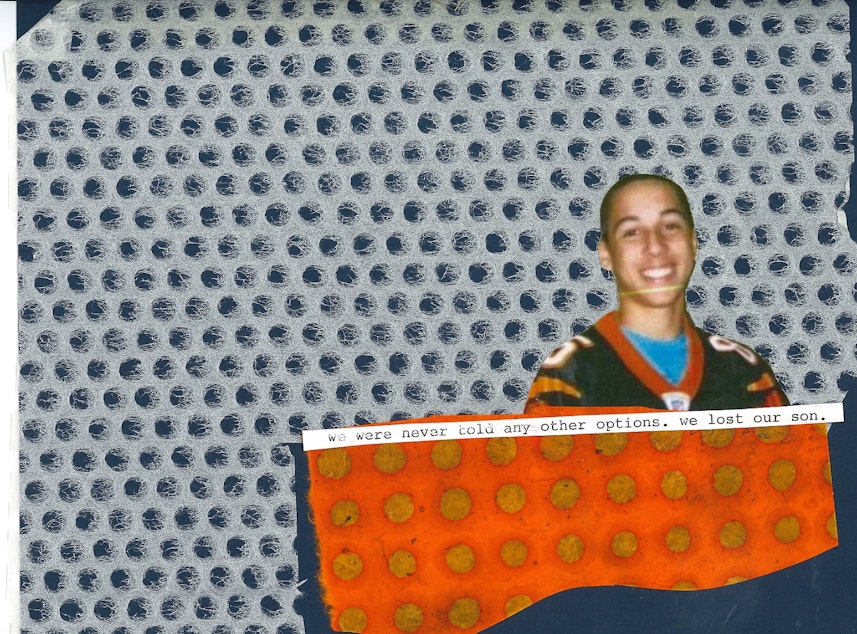

Among them, Willie and Deborah Binion.

The Binions appeared before lawmakers in 2011. They told the story of their son Jordan, who experienced psychotic symptoms starting at 16.

[Read part 1 of this series: Alex was depressed. But he was 13, so his mom couldn’t check in with his therapist.]

Jordan was briefly admitted to a hospital, but then he discharged himself. Five months later, Jordan was dead, of a suicide.

“We were never told any options or choices that we had,” Deborah Binion said. “It was just strictly, ‘It’s all up to Jordan. If Jordan doesn’t want to do it, there is nothing you can do.’"

“We lost our son,” Deborah Binion continued. “We can never bring our son back. But we do not want anybody else ever to go through what we did.”

Those who favor allowing parents access are predictably, parents.

Kids ... less enthusiastic. Remember Alex from our earlier story? He’s the north Seattle kid who became depressed and suicidal when was 13.

He said he worries about providers sharing more information with parents, because there are just some things that teens don’t want shared.

“If I had thought that my parents would find out about what’s going on with me, then I wouldn’t have been able to trust my therapist to any point,” he said.

Alex said giving parents rights to force teens into outpatient treatment won’t necessarily help if the teens are not ready to do the work.

“That would have put me even farther behind in treatment because I wouldn’t have been able to trust anyone with anything,” he said.

W

hy 13?

Here’s the late Representative Jim West, a Spokane Republican, questioning William Hagens, a staff member for the Washington State House of Representatives, during a committee meeting in 1985.

West: “Where do we get this idea that 13 is the age of emancipation for mental health?”

Hagens: “There’s no litmus test for this. Some cultures should probably be 8, and some cultures should probably be 14. Thirteen has sort of been bandied around by clinicians and people who do research in this field for a long time...”

There is no way you can find one age that is appropriate for every child, Hagens said, but you have a draw a line somewhere.

The provision was meant to give kids 13 and older easy access to mental health treatment. It was aimed at kids who were homeless or abused or who were otherwise estranged from their parents. It was also meant to give teens confidentiality between themselves and their therapists.

As a result, teens have broad authority over their treatment. They can keep any information, including their diagnosis, confidential, even from their parents.

Brewer, the Seattle Children’s Hospital administrator, said the law was not intended to exclude parents, but that’s what happened.

Brewer believes parents should be involved — that it’s clinically important. When her clients turn 13, she celebrates by having them sign consent forms.

Problems arise when teens don’t want to sign those forms, or don’t want mental health treatment in the first place.

Peggy Dolane, a mom of two kids, knows this first-hand. Her kids have struggled with mental health issues and have both at times resisted treatment. Their cases are complicated, but Dolane said there is one thing she is clear on: The law enables children’s defiance of their parents, she said.

“The child turns 13, and they are cooperating in therapy, and then the therapist announces to them on their 13th birthday, ‘And, oh, by the way, you don’t have to do this anymore, it’s up to you,’” she said.

Dolane said she was so frustrated that she looked into changing the law. She found that parents have been behind more than a dozen legislative efforts to change the age of consent law, but with little success.

The fight largely fell along partisan lines, with Republicans backing more parental rights, and Democrats trying to maintain the rights of children.

It took parents years to carve out one important exception to the law. In cases of acute crisis, parents can bring their kids to a hospital for evaluation without their consent. That’s called parent-initiated treatment.

But further efforts to expand parents' rights have not gone well.

“I was told 2 ½ years ago that this issue has been attempted to dealt with for 40 years and the best minds have tried to solve it, it’s not solvable, go work on something else," Dolane said. “As a parent, I’m like, no, this is wrong!”

She persisted. She was spurred on by the growing number of parents whose kids experience mental health problems, and by a growing body of research that shows adolescent brains aren’t fully developed until they are well into their 20s.

For the past year, Dolane has worked with lawmakers, parents, health care providers, youth advocates and others. They were tasked by the Legislature to find a compromise.

I

n December, after 21 meetings, the group came out with a series of recommendations. They were unanimously approved by the legislature's Children's Mental Health Work Group, a key first step towards moving them into legislation.

The recommendations would keep the state’s age of consent at 13, so teens can continue to seek treatment on their own.

But providers would be allowed to share critical information with parents, including their teen’s diagnosis, treatment progress, medications, and crisis planning.

Parents would also be allowed to take their kids to a limited number of outpatient sessions, and could provide consent even if the teens were unwilling.

Peggy Dolane said it’s not everything she wanted, but it’s progress for parents in Washington state.

State Rep. Noel Frame is now working those recommendations into legislation. The goal is to bring it before lawmakers this year.

Deborah Wang is spending the year doing stories on teenagers and mental health as part of a Rosalynn Carter Mental Health Journalism Fellowship. If you have a story you would like to share with Deborah, please email youthmentalhealth@kuow.org.