As youth suicides increase, these teens want to save lives

The Day of Hope begins with a room of high school students making lists.

Harry Brown leads the exercise. He’s a mental health counselor for the Mercer Island School District.

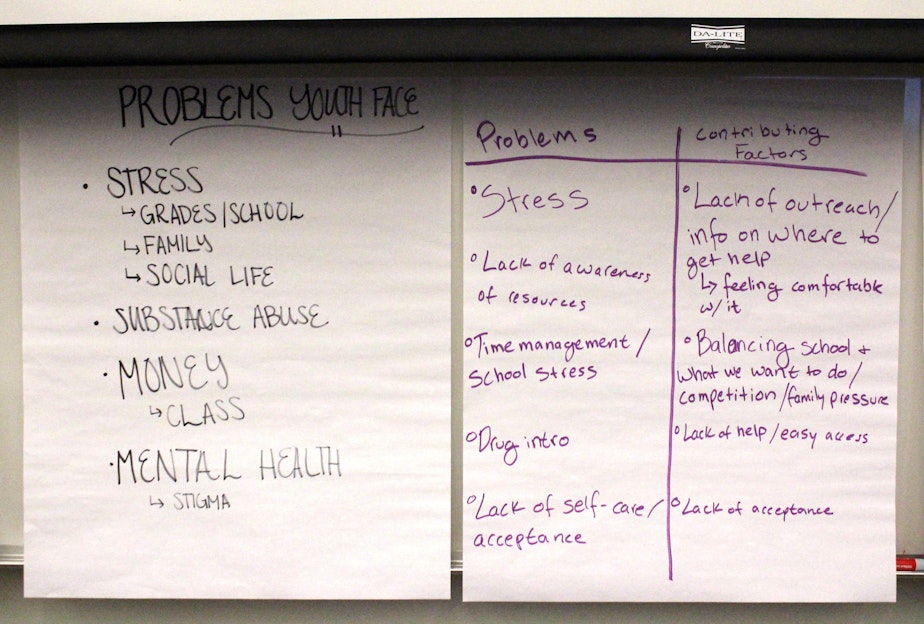

He asks the students: What are the most pressing problems they see at their schools?

The students write on large posters: anxiety, substance abuse, eating disorders, depression, peer and academic pressure, social media, suicidal ideation...

The lists are long. As the students pin them to the wall, Brown acknowledges the obvious—being a teenager these days can be hard.

“I really appreciate everyone’s courage and honesty to talk about what is going on,” he tells them. “It can feel like a really heavy lift.”

Sponsored

These kids have come here from all over Washington state—Seattle, Shoreline, Auburn, Okanogan, Mount Si.

They're here because their high schools have partnered with Forefront in the Schools, a program of the Forefront Suicide Prevention at the University of Washington.

The goal of the four-year-old schools program is to reduce the incidence of suicide by improving the mental health climate at schools. A central focus is in organizing students to lead the charge.

“When you want to change the entire culture in your school, how do you do that? Well, you do that from the ground up,” said Phoebe Terhaar, the coordinator for Forefront in the Schools.

Sponsored

The program focuses on educating students about mental health and training them to be responsive to mental health challenges among their peers—when kids struggle, they may not seek out help from adults.

“You definitely have a fraction of students who feel isolated, who feel this isn’t something I can divulge to an adult and so I am just going to tell my friend,” Terhaar said.

Students also play an important role in reducing stigma and in figuring out the best ways to deliver support in schools, Terhaar said.

S

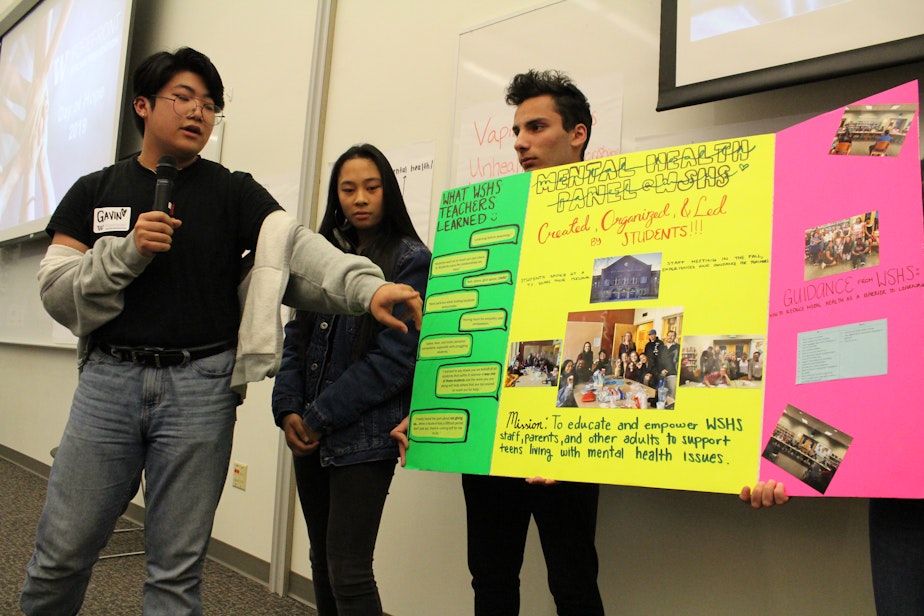

o on this day, which the program has dubbed the Day of Hope, student teams give presentations on what they’ve been doing to change the culture around mental health at their schools.

Sponsored

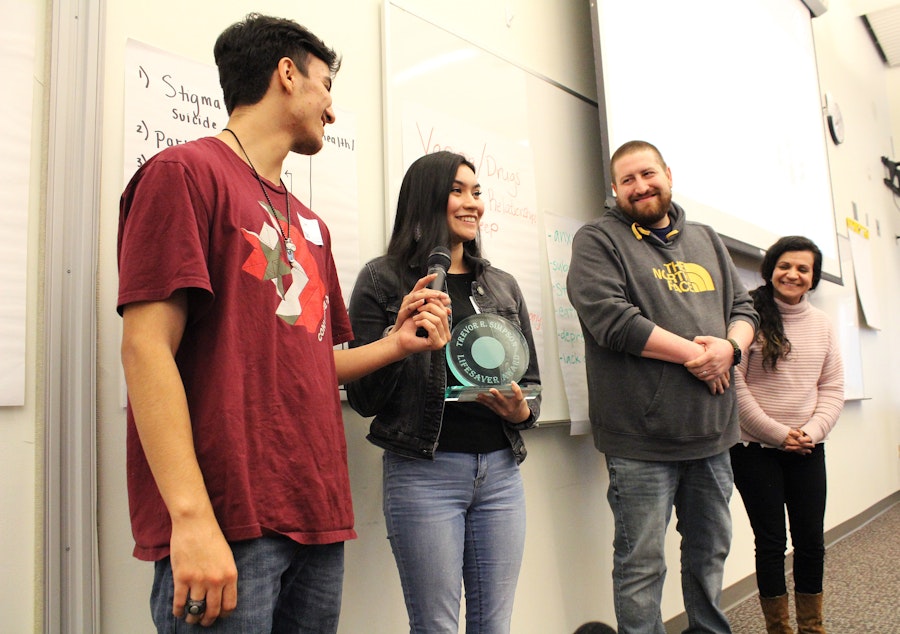

They are competing for the Trevor R. Simpson Award. It's presented by Scot and Leah Simpson, who lost son Trevor to suicide in 1992. The award comes with $1,000 in prize money, which was donated by the Simpsons.

Over the past year, the student teams have participated in marches, done random acts of kindness, held educational events, and trained teachers and staff on how to support kids who struggle with mental illnesses. They've sold mugs with information on mental health resources attached.

But the team that was declared the winner was the one with a powerful personal story.

Dominic Jansen is a member of the Muckleshoot Tribe and a senior at the Muckleshoot Tribal School. His project grew out of his experiences as a young kid, when he battled isolation, loneliness, and depression.

Sponsored

“I began contemplating thoughts of suicide. How to get rid of myself in the easiest, fastest way possible. Without any pain,” he said.

During high school, Dominic says he lost a good friend to suicide.

Student Raven Stephenson experienced the same loss. Her friend was a senior. She was smart, and she also struggled with mental illness.

“And it was really, really hard because I was trying to live up to what she is because she was the 'it' person at our school. And she dealt with things that I dealt with," Raven said.

When Dominic heard of a third grader who was contemplating suicide, he said it hit him hard.

Sponsored

That’s when he decided to form a peer mentoring group of six high schoolers. They are available to talk with middle schoolers who are struggling, who need help in school, or who just want comfort.

Teachers connect middle schoolers with these high school peer mentors. They get time off from class to meet.

“This project means a lot to everybody that’s with us," Raven said. "The six of us all have our own reasoning for doing it. And we want to do it well for our community and for the kids of our school, because we’ve all been there."

These efforts are especially noteworthy in a community that is deeply affected by suicide. Native Americans and Alaska Natives have the highest suicide rate of any group.

I

t’s impossible to say whether these and other efforts underway in the schools will eventually succeed in preventing suicides.

The Forefront in the Schools program is only in its fourth year, and organizers say they are still studying the program to see how to gauge its effects.

Phoebe Terhaar says the whole field of suicide prevention is developing.

But she believes a continual, intensive, multi-leveled approach to mental health is what is needed in the schools. There needs to be more data before they can corroborate that hunch. "It'll be great when we can put that together."

Read more: 4 teens died by suicide in Seattle area in recent days

Read more: The kids are not alright. High schools grapple with rising rates of mental illness

Deborah Wang is spending the year doing stories on adolescents and mental health as part of a Rosalynn Carter Mental Health Journalism Fellowship. If you have a story you would like to share with Deborah, please email youthmentalhealth@kuow.org.