The cutest carbon culprits? Your pets

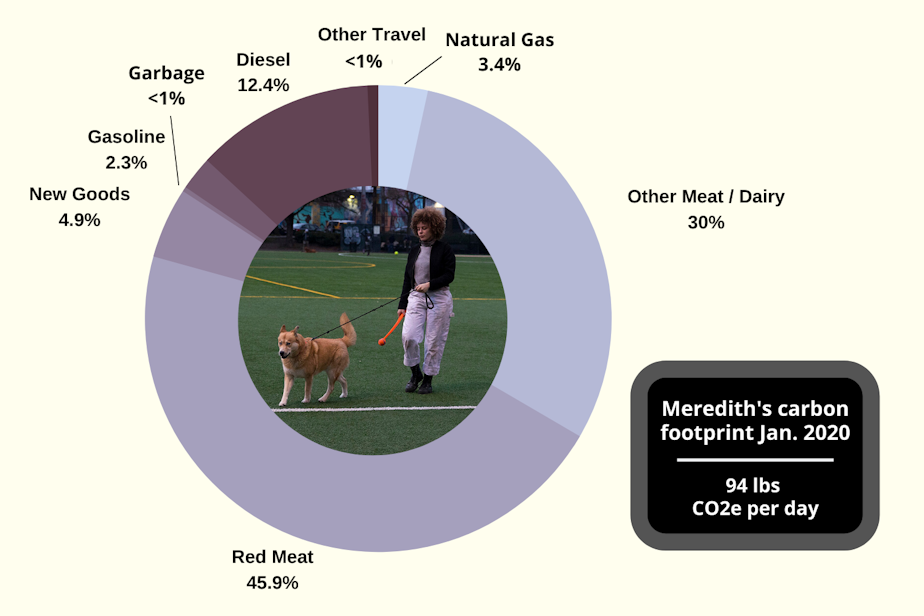

Tracking her daily habits for KUOW’s Biggest Carbon Loser contest, Meredith Cooper learned that most of her carbon footprint comes not from her decades-old, diesel-guzzling Mercedes, but from the food she buys.

It wasn't even her own food so much as what she feeds her dog and her cat.

Overall, nearly half of Cooper’s carbon footprint is actually a carbon paw-print.

KUOW has been following three people in the Seattle area as they try to change their climate-harming ways. Contestants spent January tallying their carbon emissions from their energy use, travel, food and shopping. They have the month of February to reduce their carbon footprint as much as possible and become the Biggest Carbon Loser.

Despite holding down three jobs to piece together a living, Cooper drives a lot less than most Americans.

The bartender-handywoman-apartment manager lives in Seattle’s dense, transit-friendly Capitol Hill neighborhood, and her work is rarely far from her apartment building.

“As long as I give myself enough time to be where I need to be, typically, I can get there without driving the car,” she said.

Sponsored

Her densely urban lifestyle and working-class income combine to give her a modest carbon footprint, by modern American standards, of about 94 pounds of carbon dioxide a day. It’s less than half those of Will Wilson and B Merikle, her two competitors aiming to become KUOW’s Biggest Carbon Loser.

(You can calculate your own footprint here.)

Unlike her dog, Sun Ra, and her cat, Li’l Cig, Cooper has a mostly vegetarian diet. The upshot is that her pets’ diets do more damage to the climate than the larger volume of food that she eats.

As a cat, Li’l Cig is a pure carnivore but eats a lot less food than the much larger Sun Ra (who’s a SUCH A GOOD GIRL in this reporter’s estimation), an 8-year-old husky mix who weighs about 55 pounds.

“She sorta looks like a corgi with long legs,” Cooper said.

Sponsored

Sun Ra mostly eats dog food with beef as its leading ingredient.

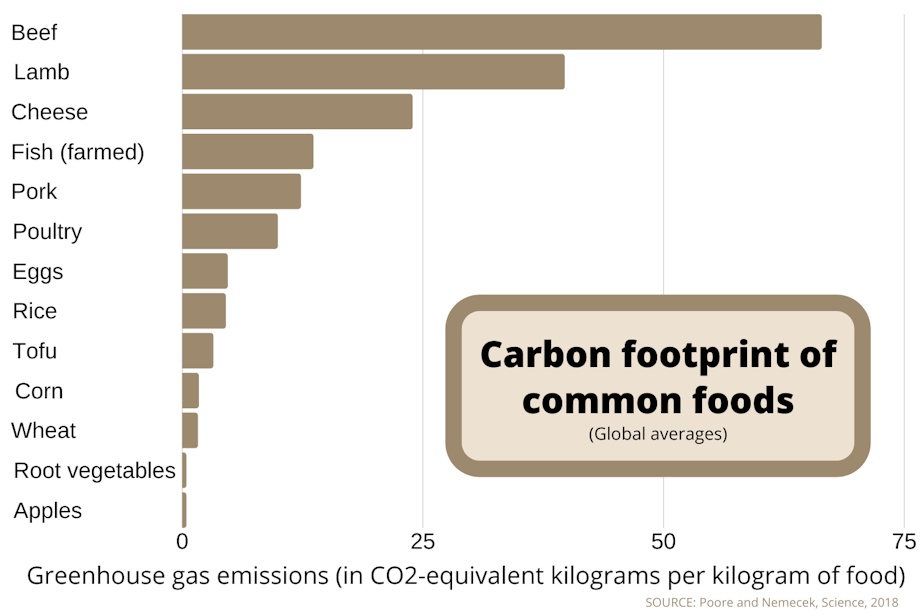

Of all types of meat, beef is the worst climate culprit.

Sun Ra’s dietary mainstay is a dry dog food called Orijen Regional Red that has more than 50 ingredients. It’s about half beef and meat from other cud-chewing, methane-belching animals like lamb and bison.

Sun Ra’s beefy diet gives her an unusually large carbon paw-print for a pooch of her size.

Chicken, with its much lower carbon footprint than beef, is the most popular variety of both dog food and cat food in the United States, according to the market research firm GfK.

Sponsored

Cooper says getting her dog to try different foods isn’t hard.

“She'll eat anything,” Cooper said with a laugh.

Even so, Sun Ra’s paw-print-reducing options are limited.

“She's actually allergic to chicken and fish,” Cooper said. “She gets really itchy and she scratches bald areas if I give her fish or chicken.”

Animal products, and especially beef, have much higher carbon footprints than plant-based foods.

Sponsored

In a city where dogs outnumber children nearly 2 to 1, and a nation with the most pets on earth, the paw-prints of our beloved little carnivores and omnivores add up.

Disclosure: this reporter has two cats.

“We have pets. We have to feed them meat. They demand it, and that impacts our carbon footprint,” Cooper said. “But then I was thinking, you know what? I bet kids eat a lot more meat or anyway, they have a higher impact on your carbon footprint, and they live way longer. So weighing those two things, I felt better.”

“I don't know. That's a very Seattle thing to compare,” she laughed.

Sponsored

The United States produces about 8 billion tons of pet food a year.

Nearly a third of all climate harm from U.S. agriculture comes from pet food, according to an estimate by University of California Los Angeles geographer Gregory Okin.

Agriculture overall causes about 10 percent of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Globally, some estimates put agriculture’s toll at closer to 25 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions.

To cut down on her own carbon, Cooper has challenged herself to only purchase plant-based foods for the month of February.

What does she miss most? Cheese.

“It’s been a little harder than I expected,” she said. “To be candid, it’s kind of sucked.” Cooper said she’s having “dairy withdrawals.” “Nut cheese -- It's not hittin', you know?” she said. “It doesn't have that fatty tang, but maybe if you eat it long enough?”

Despite Cooper’s cheese cravings, in the first two weeks of February she managed to cut her carbon footprint nearly in half.

The cows that make all that dairy and beef add up to a real global threat.

Methane from cattle belches caused about 4 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions in the United States in 2016, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

“Most livestock production is conventional and has a horrible climate footprint,” said University of Washington geologist David Montgomery, who studies soil and agriculture as well as rocks.

“Not all cows are bad for the climate. It depends on what they’re eating, how they're raised, how they’re grazed,” he said.

Montgomery has become an advocate of regenerative agriculture or, as it’s sometimes called, carbon farming. It grows plants both to provide food and to pull carbon out of the air and capture it in the soil.

Cattle grazing is one of its tools: Carefully managed grazing can stimulate grasses to put on underground growth.

“We sequester a lot of carbon out here,” said Snoqualmie Valley cattle farmer Jim Haack, who grazes his small herd of cattle on a lush floodplain at the foot of the Washington Cascades.

But it takes a lot of land to graze cattle in a way that also stores carbon underground.

In addition, the science is still unclear whether carbon farming can tame cows’ belches of heat-trapping methane. The super-powerful greenhouse gas can trap 90 times more heat than the same amount of carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. Over a century, it traps 30 times more.

Animal scientist Ermias Kebreab at the University of California, Davis, has found that adding seaweed to cattle feed can reduce cows’ methane belches by half. Yet Kebreab and other livestock researchers say that cows that graze on grass belch even more methane than those that are fed grain.

“We in the developed world should probably be eating less meat, but if you're going to eat meat, eat meat that's raised in a more environmentally friendly and climate-sensitive style,” Montgomery said.

As for finding climate-friendly protein for a dog or cat, that can be tough. Wander down the pet-food aisle of a pet store or supermarket and you’ll face a dizzying array of unregulated marketing claims that verge on the meaningless, like “natural”, “human-grade,” “holistic” and “premium.”

“When we go to buy dog food, it's a little obnoxious,” Cooper said. “We really have to read the labels and are, like, should we feed her grains? Should we get chicken? We don't know!”

Determining the carbon footprint of pet food can be difficult: the foods are often complicated recipes, with only minimally useful information provided on the label.

Pets and livestock traditionally ate a lot of kitchen and crop waste, rather than food specifically produced for them. But animal diets have shifted in the other direction, especially with a recent trend toward the “humanization” of pet products.

Pet-food marketers have been trying to convince pet owners that “human-grade” ingredients are more nutritious than animal byproducts, like bone meal or organ meat, that might have become waste otherwise.

“Pets need good-quality food, but they don’t have to compete for the same steak their owner is buying when they will happily and healthily eat organ meats or less-pretty trimmings,” veterinary nutritionist Cailin Heinze writes.

The Big Picture

For the Biggest Carbon Loser contest, KUOW brought in Seattle environmental consultant Sean Watts to coach Cooper on her best carbon-saving options, including cutting back on beef. He also coached Cooper to keep her eye on the big picture.

“You can only do so much,” Watts said. “Try to do that and think about how you can effect large-scale policy.”

“Our great hope is in the non-linearity of social change,” Watts said. “Nothing seems to change, but there comes a tipping point when suddenly there's a lot of change.”

Think of the sudden collapse of Soviet communism or the rapid acceptance of gay marriage.

On a smaller scale, Watts suggested Cooper consider trying to push the historic, 41-unit condo building she manages to incorporate more energy-saving technologies.

“As a manager, you might have an outsized influence,” Watts said. “People take our suggestions about what should be done to make the building efficient and a great place to live pretty seriously,” Cooper said. “So I think there's some wiggle room there.”

Cooper said she sees a role for both individual consumer choices and large-scale, systemic reform in fighting climate change.

“If we're living lives where we're consuming and paying for things that have a high carbon footprint, then what's the incentive for systemic change?” she asked. “But if we are trying to change those things and demanding that there's systemic change at the same time, then I think that's probably what gets us there.”

Advocates in Olympia are trying to get Washington state to give grants to farmers who adopt carbon-saving or carbon-farming measures. Similar measures have been introduced in Congress.

Voluntary measures, whether by farmers or consumers, can be at least a step in the climate-friendly direction. Options for reducing carbon paw-prints include:

• Avoid beef and lamb-based products in favor of lower-carbon protein sources like chicken, fish or pork.

• Avoid overfeeding your pet. Obesity is a major health problem for American pets as well as their owners: one-third of U.S. dogs and cats are considered overweight or obese.

• Next time you get a pet, consider getting a smaller one (they eat less, of course) or a vegetarian one (like a bird, rabbit or hamster).

• Remember that your pet is not a human and does not need “human-grade” food.

• Remember that dogs are omnivores: their food does not need to be 100% meat. “A dog doesn’t need to eat steak,” UCLA’s Okin said.

• Spay or neuter your pet to prevent unwanted pet population growth.

Still, climate experts agree there’s an urgent need for much more than voluntary measures: They say a rapid overhaul of our carbon-dependent economy is required to fend off climate catastrophe.

Stay tuned! We will reveal the winner of KUOW’s Biggest Carbon Loser contest at our That's Debatable event Mar. 11 at Seattle University.