She was jailed for shoplifting. A month later she was dead

In November 2017, Piper Travis, 34, was pulled over south of Marysville.

It was a routine traffic stop, according to the state trooper’s report, but a warrant check turned up two misdemeanor cases for which she hadn’t appeared in court. They were both for allegedly trespassing at and stealing from Walmart: one case dealt with a stolen TV, and another with a $3.48 bag of Easter candy.

Travis was arrested and held on bond in Snohomish County jail to await trial. Eleven days later, she was observed lying on the floor of her cell, foaming at the mouth. Two weeks after that, she was dead.

Travis’s parents detailed her final days in a lawsuit they filed in federal court. Travis died of pneumococcal meningitis, which swelled her brain until it shut down her body. The lawsuit says that jail staff dismissed Travis’s suffering as she screamed, foamed at the mouth, urinated and defecated on herself – and neglected to conduct a meaningful medical evaluation until it was too late.

Sponsored

T

ravis’s death in December 2017 didn’t make headlines. An obituary in The Herald of Everett noted that she died in the hospital, surrounded by family.

Around the time Travis was arrested, the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office was making the news for other reasons. After a string of jail deaths, millions paid out in lawsuit settlements to families of the deceased and a 2013 National Institute of Corrections review pointing out concern over jail overcrowding and medical understaffing, the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office had made a series of highly praised reforms.

After Ty Trenary became sheriff in 2013, he set booking restrictions for low-level offenders with medical or mental health issues to decrease overcrowding. The Sheriff’s Office ended contracts with neighboring municipalities to further bring down the average daily jail population, and Trenary asked to double staff in the jail’s medical unit. The jail instituted new medical screenings at booking, too.

Sponsored

The jail’s average daily population fell, and Snohomish County didn’t report jail deaths for 2015 or 2016. Gov. Jay Inslee toured the jail and declared Snohomish County a “state leader in jail diversion.”

But Cheryl Snow, the lawyer representing Travis’s parents, believes that praise may have been premature.

“When you look at this case, you can't help but scratch your head and think: You have somebody coming in on a minor misdemeanor charges who dies in your care,” she said.

Travis’s parents, Paulette and Gregory Beck, meanwhile, want an explanation – and they want the jail to make changes so no one else has to die like their daughter.

“How could someone who apparently appeared healthy when checked into the jail go through all of that?” Paulette Beck said.

Sponsored

T

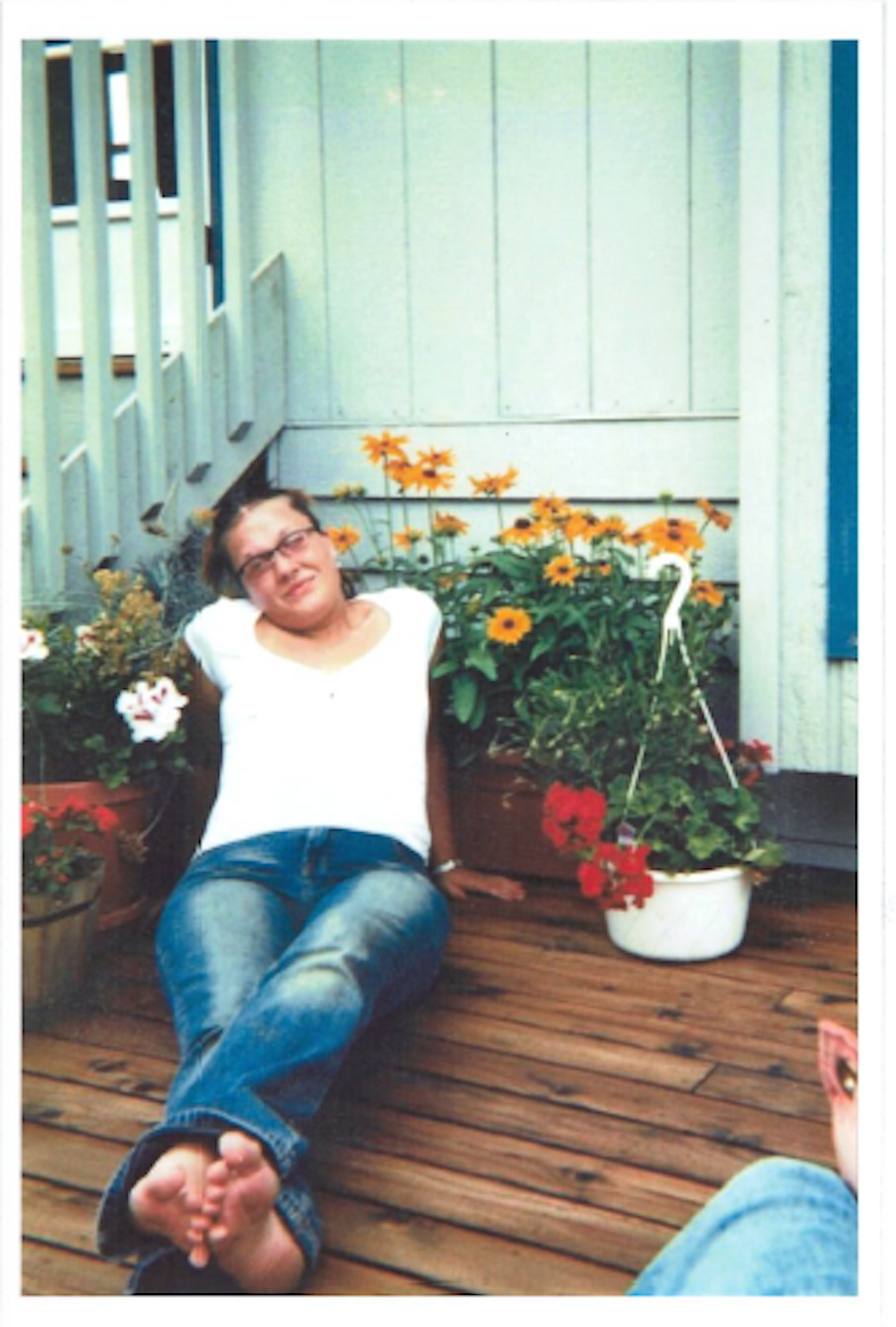

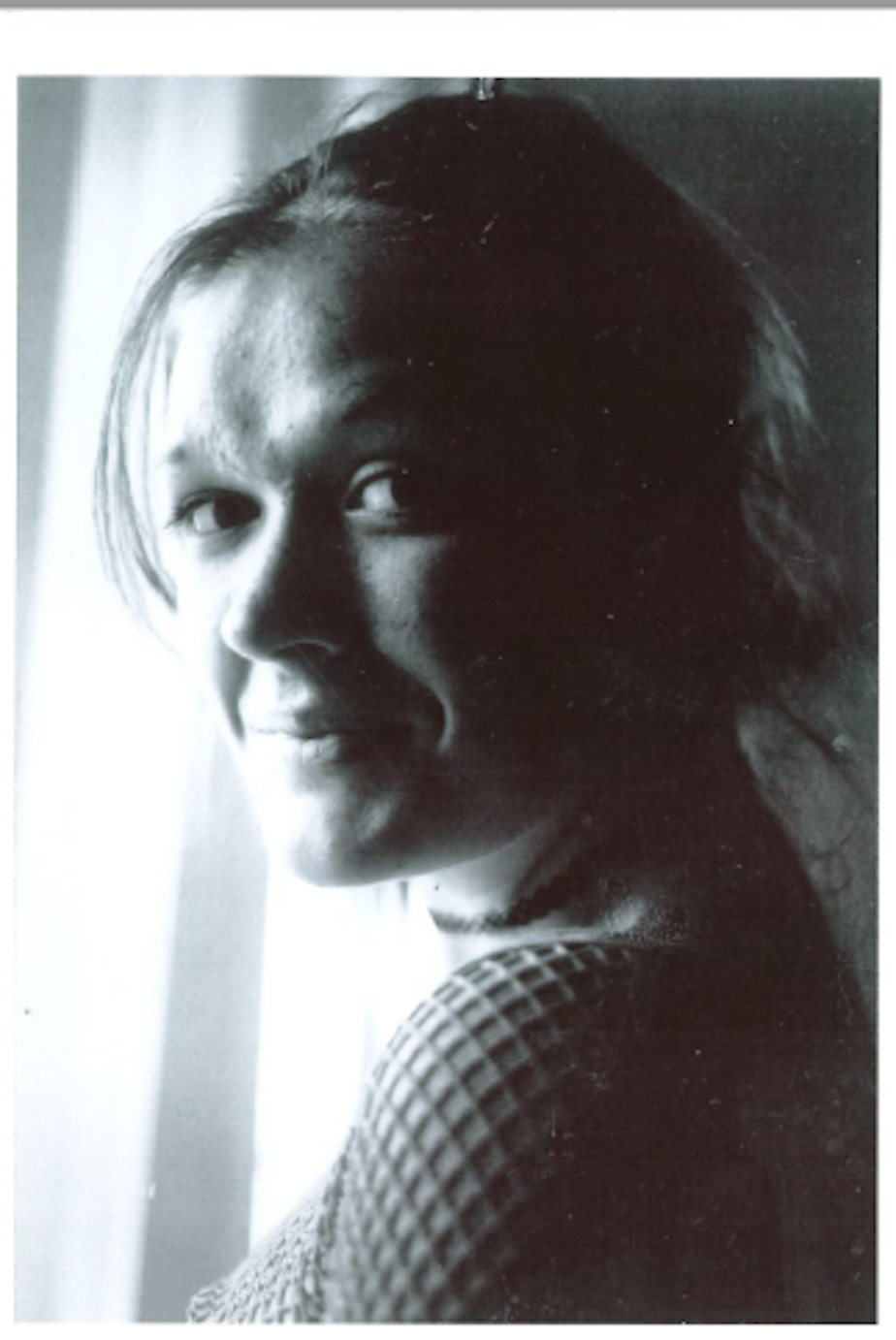

ravis’s whole life was on Whidbey Island. Her house, her friends, the food bank where she volunteered – she was content where she was, the Becks said.

You can’t quite see Travis’s house from the Becks’ living room, but she lived just across the bay, a six-minute drive away. They saw each other five days out of seven, the Becks said.

Sponsored

Travis’s childhood bedroom in the Becks’ home contains binders of poetry that she wrote in high school. She was diagnosed with bipolar disorder as a teen, Paulette Beck said, and poetry was an emotional outlet. Travis wrote poetry until the day of her arrest.

From the back of the program at her funeral were lines from a poem Travis wrote when she was 18: “Posing for pictures, as the poster child for the rebellious teen, will leave you spinning and kidding around and around, so just remember… in the end we all fall down.

“Will you get back up?”

Travis’s life would have looked different without the Becks. When she was 2, she was in a car crash that killed her mother and her older sister. Doctors told Paulette Beck that the head injury she sustained as a toddler may have contributed to the later bipolar diagnosis.

Travis went to live with the Becks – Paulette Beck was her mother’s sister – and they raised her as their own.

Sponsored

“Three weeks didn't go by when she said, ‘Can I call you Mom?’” Paulette Beck said. “I said yeah. And then she said [to Greg], ‘Can I call you dad?’”

Travis thrived at the alternative high school she attended on Whidbey, Paulette Beck said. She graduated early and won six local scholarships owing to her writing skills. She spent half a year at Everett Community College, but it didn’t stick: Travis struggled with timed tests, Paulette Beck said, a cognitive consequence of her bipolar disorder.

Travis later graduated from manicurist school in California, but getting her license required a timed test, Travis's kryptonite. So, feeling the itch to travel, she crisscrossed the country with her boyfriend at the time, a long-haul trucker.

Back on Whidbey Island, Travis moved into a house that her grandparents had placed in trust for her. She relied on Social Security and the food bank to cover her basic needs. She volunteered at the food bank to give back, too.

The food bank was one of the social centers of Travis’s life. “She knew so many people on the south end that she couldn’t go to Clinton or Langley and not run into multiple people that stopped and talked to her because she knew them,” Paulette Beck said.

Travis, her friend Karmen Chastain said, was “attentive to people’s needs” and had a “sixth sense about when somebody just needed some quiet or sympathetic ear.” Chastain described her friend as bright, bubbly and engaging – and, she said fondly, “a beautiful mess.”

Travis, Chastain said, never showed up on time and had fabulous style. She bought clothes in thrift shops and often wore her hair in pigtails. One outfit Chastain remembers as Travis’s “bumblebee” getup because she dressed in yellow and black stripes, with a matching pair of high-heeled boots.

Travis liked to golf. Chastain and her husband remember Travis teeing off in platform heels. “She did it with effortless grace, believe it or not,” Chastain said. “It was really an impressive feat.”

And Travis took in lost souls. A man who attended her funeral said that when he was down on his luck with a meth addiction, Travis invited him in as he got clean.

After she died, the Becks installed a cedar bench at the entrance of the food bank to honor her. On it, an artist carved her favorite flowers. The Becks asked people who attended Travis’s funeral to donate to the food bank in her memory; they donated hundreds of dollars, Paulette said.

It was too painful for the Becks to clear out Travis’s house after her death. Relatives who did said they found hundreds of spiral notebooks with her poetry.

“I miss her every damn day,” Chastain said. “She was definitely a bright spot in our lives.”

U

pon arrival at the jail, Travis underwent a medical screening that deemed her fit for booking. According to a document filed by the county in federal court, she was booked into the jail’s mental health module — an area with fewer beds but regularly overcapacity — because of her bipolar disorder and prior misdemeanor bookings.

The following morning, Travis pleaded not guilty in court to the misdemeanor charges, and returned to her cell to await trial. Over the next 11 days, Travis began to show signs that she was unwell, but she would receive little help from jail staff, according to the lawsuit.

Between November 21 and November 27, the lawsuit said, Travis stayed in her cell all day, besides an hour of recreation time. But in the early morning hours of November 28, a deputy noticed Travis crying in her cell from what she described as a “terrible headache.”

The deputy asked medical staff to evaluate her, according to the suit, and a jail nurse arrived. Travis told the nurse that the pain level was uncommon, the lawsuit says, and suggested it may have been the result of “sabotage” from other inmates. The nurse gave Travis ibuprofen.

Travis, however, continued to “make noises of pain and anguish” for hours after she was given the ibuprofen, according to the lawsuit. The deputy who asked for her original medical evaluation told her to quiet down.

Later that day, Travis didn’t go out for rec time because of the headache and refused lunch and a meeting with a lawyer. The following day, another deputy noted that Travis was “making strange noises” and was “very slow to process instructions.” That deputy took away Travis’s rec time.

A third deputy noted that Travis had been “moaning sporadically all day.” After she refused to return her meal tray, he ordered that she receive a sack lunch for three days.

The following morning, Travis refused breakfast and had taken off her pants. She was screaming, a deputy noted.

Later in the day, the deputy who ordered Travis’s sack lunches observed that Travis had feces on her hands, uniform and the wall of her cell. When he asked her to shower, he noted her shuffling.

By midnight, a fourth deputy doing welfare checks noticed Travis was “exhibiting abnormal behavior.” She was partially naked and wouldn’t look directly at the deputy when she knocked on her door and asked her to put on her pants.

“Her eyes would sort of roll back halfway, clenched fists, tensed body, shaking, breathing fast, yelling, and incoherent,” the deputy said, according to the lawsuit. “She looked like she was in pain, but since she wasn’t talking, I really did not know where she stood. I know she is incoherent and slow to process directives/information, but I had a weird feeling about her well-being.”

The deputy asked for medical attention, and a nurse arrived. The nurse observed that Travis screamed and urinated on herself, and wouldn’t answer to her name.

The nurse did not take Travis’s vital signs, according to the lawsuit, and said that when she tried to measure Travis’s blood oxygen saturation, Travis wouldn’t cooperate. The nurse ordered that Travis go to the observation unit for a behavioral assessment and planned to notify the jail’s mental health provider.

The lawsuit says that the nurse left without plans for a medical follow-up, a claim the county denies. Jail surveillance footage show deputies then taking Travis to the observation unit by wheelchair.

Observations recorded every half hour after Travis was put on behavioral watch describe Travis yelling, screaming, making noises on the floor and refusing breakfast. When the jail mental health provider visited Travis with a nurse, the nurse said she was unable to take Travis’s vital signs because of her resistance. A medical appointment was scheduled for three days out.

Back on the half-hour observation watch, a deputy observed Travis refusing dinner and foaming at the mouth on the floor, according to the lawsuit. The lawsuit says a nurse took Travis’s vital signs and noted that Travis was also hyperventilating, having rapid eye movements and not communicating.

According to the suit, the nurse called an EMT team for a psychological evaluation. When the EMTs arrived, the lawsuit says that jail staff suggested to the EMTs that Travis was “faking it.”

But when EMTs found Travis with a 102-degree temperature and observed seizure activity, they transported her directly to the hospital, according to the lawsuit. The lawsuit says the EMTs checked off “possible neglect” in their paperwork.

Responding to the complaint filed in federal court, the county denied that its employees ignored Travis’s symptoms and didn’t offer treatment. The county also denied that employees suggested to EMTs that Travis may have been faking her symptoms or only experiencing a psychological issue.

The Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office, which oversees the jail, declined to comment on Travis’s pending case. The Snohomish County Prosecutor’s Office, the Snohomish County Executive and Health Pros Northwest, a company contracted by Snohomish County to provide medical support inside the jail, also declined to respond.

A

t the hospital, doctors diagnosed Travis with sepsis, pneumococcal meningitis, and acute respiratory distress. They decided to induce a coma.

Community-acquired bacterial meningitis can be an aggressive and often fatal infection. Among the usual causes of the illness, pneumococcus bacteria are some of the most common. Pneumococcal meningitis also has the worst prognosis, said Dr. Christina Marra, who specializes in neurology and nervous system infections at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

The bacteria can be carried in the nose and cause an infection elsewhere in the body; people over 65 are encouraged to vaccinate for it. From an infection in the ear or elsewhere, it can enter the blood and then the spinal fluid.

After signs of an initial fever or stiffness in the neck, the illness moves fast, in just a matter of days: Once the brain swells, there isn’t much space for it to go, and it shuts down vital structures at the top of the spine.

Four days after Travis was hospitalized, the Becks learned she was there. They were confused, they said, and had no idea what was going on.

A week later, Travis showed no signs of brain activity, and doctors recommended removing life support. She was unable to breathe sufficiently on her own and died on December 16.

Snohomish County Public Defender Kathleen Kyle called the case “devastating.” Kyle credited the Snohomish County Corrections Department with instituting massive changes since 2013, but said that mass incarceration still plagues the criminal justice system.

“We need to stop incarcerating so many people,” Kyle added. “In Snohomish County, generally there's this idea of we're doing better than these other places, but that's not the lens we should be looking at this through. We're contributing to mass incarceration just as much as our neighbors.”

The Snohomish County Jail didn’t report any new jail deaths in 2015 or 2016, when many of the new reforms came online. The average daily jail population dropped from 1,175 to 813 between 2013 and 2016.

But in 2017, for the first time in four years, the average daily population increased to 958, according to the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office. The jail reported two deaths in 2017, and another in 2018.

Today, Paulette Beck speaks quietly about her daughter’s death. She doesn’t understand how her daughter could have gotten so ill “without any action,” she said. “We just want to know how that could happen.”