There's a drug that could help opioid addiction. The trick is to find someone to prescribe it

Linda Hargrove takes white Suboxone tablets daily, dissolving them in her mouth. She’s used to the taste: chalky, not real bitter. Still, Hargrove sips juice from a straw to wash it down.

Suboxone, the brand name of the medication Buprenorphine plus the overdose antidote, Naloxone, is an effective treatment that can help people addicted to opioids and save lives. But few doctors prescribe it.

Last year in King County over three hundred died from overdoses, a record number.

Hargrove is married, has four grandkids, and goes to church every Sunday.

Twelve years ago she had major surgery. “I was in the hospital maybe three weeks, and then I came home,” Hargrove said. “But in that time I was on pain medication and I grew dependent.”

Sponsored

For over two years, she got pills like oxycodone from a friend or by going doctor to doctor, making up “stories” about why she needed them. Without them, she felt sick.

“Just icky. Sweaty. I felt crampy, irritable, not wanting to be bothered,” Hargrove said.

Now Hargrove is in treatment and has been in recovery for eight years.

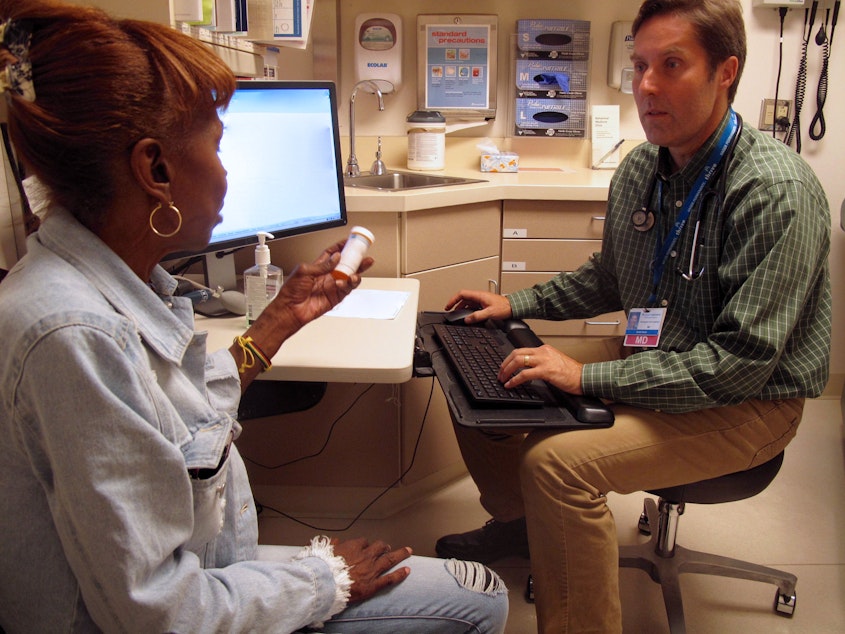

One day recently she met with her doctor, Grant Scull at Kaiser Permanente on Capitol Hill, who checked up on how the medication was working for her. Dr. Scull is one of the few providers in the area who treat addiction with Suboxone.

The medication works in the body’s pain receptors, he said.

Sponsored

“When someone takes an opioid — heroin, oxycodone are examples — [the opioids] have to go to a little attachment on the cell’s surface in order for them to be active in our bodies. It’s the place where the molecule plugs in to have its effect,” Scull said.

Suboxone plugs in too. It keeps other opioids, like pain pills and heroin, out of the way. So, it satisfies the body and keeps a person from feeling sick, getting high or overdosing.

Patients get relief from constantly seeking drugs and can focus on normal life again.

“They are then able to take a medicine once a day that they know will protect them from overdose, protect them from withdrawal and allow them to engage in their normal activities,” Scull said. “And I think that’s the transformative element of Suboxone.”

More and more clinics, including providers like Swedish and Neighborcare Health, are making the medication available.

Sponsored

Still, the uptake is slow. Physicians have to undergo special training and obtain federal licenses to prescribe the medication to treat addiction. Also, some family doctors are reluctant to treat addicted people because opioid dependent patients can exhibit disruptive behaviors when they’re seeking more pain pills, Scull said.

“Early refill requests, lots of phone calls to the clinic, disruptive behavior in the waiting room or in their calls to nurses — and so these experiences are hard on a clinic and the clinic staff,” he said.

But patients on Suboxone are different, third-year medical resident at Kaiser Permanente Dr. Katy Schousen said. Suboxone patients are “really invested” in their care and want to get better, often requesting the medication by name.

“They come saying I know I want this because I've been in this cycle that I want to get out of, I want to feel free from, and I know Suboxone can do it for me,” she said.

Prescribing too many opiates in the first place is one of the causes of the current crisis, so Schousen, who is part of a vanguard of new doctors incorporating it in their practices, hopes to help turn the crisis around.

Sponsored

“I think a lot about our legacy as doctors, that it's within our ability to help rectify that issue that we in some part helped create. And I love that Suboxone is a tool to help us do that,” she said.

But primary care doctors alone won’t be able to stop the crisis. To really put a dent in opioid overdose deaths, Suboxone should be easier to get than heroin, University of Washington researcher Caleb Banta-Green said.

“You should do everything you can to get everybody who needs that medication on it every single day that they want it,” he said.

That means making services available where users are, such as syringe exchanges, emergency departments and homeless encampments, or offering to take people to services, Banta-Green said.

Patients should be able to get the treatment on demand, without navigating a confusing healthcare system.

Sponsored

But one such pilot program in downtown Seattle filled up in three months. There’s a waiting list now, 100 people long.