U.S. Measles Outbreaks Are Driven By A Global Surge In The Virus

In the year 2000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared measles "eliminated" from the United States. But with measles continuing to spread and at times flourish in many parts of the globe, the U.S. has been unable to remain immune to the disease.

This year, the U.S. has its highest number of measles cases in 25 years. As of this week, the CDC has recorded 704 cases in 22 states.

The re-emergence of measles is linked to parents who have chosen not to vaccinate their children against this highly contagious disease.

But that's not the full explanation. Dr. James Goodson, a senior measles scientist at the CDC, says the U.S. outbreaks are being driven by a surge in measles globally.

The World Health Organization tallied more than 112,000 measles cases in the first quarter of 2019. This is up more than 300% compared to the same period in 2018. Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director general of WHO, calls the rise in measles "alarming" and a "global crisis."

Sponsored

Madagascar is grappling with a measles outbreak that's sickened 70,000 people and killed more than a thousand. There are also significant outbreaks in Brazil, India, the Philippines, Ukraine and Venezuela. There have been smaller flare-ups in France, Greece, Israel and Georgia.

"When we see large measles outbreaks in countries that are common destinations for U.S. travelers like we're seeing this year," Goodson says. "that's when we often see the largest number of measles cases in the U.S."

That's because of the nature of the virus. "The only reservoir for the measles virus is people," Goodson says. "So the only way you're going to get measles is if you come in contact with somebody who's infected with measles."

Measles is one of the most highly contagious human diseases known to science. Before a measles vaccine was introduced in the U.S. in the 1960s, the CDC estimates there were 3-to-4 million cases a year in the country.

Epidemiologists say that to stop the spread of the virus, 95% of people need to either be vaccinated or immune to measles because they already had the disease. In the year 2000, WHO launched a campaign to attack measles globally with the ambitious target of getting 90% of all children vaccinated before their first birthday. WHO at that point wasn't even talking about "eradicating" measles; the goal was simply to "control" it.

Sponsored

The campaign has brought the estimated number of measles cases down from nearly a million a year globally in 2000 to just over 100,000 in 2016. But since then the number has increased dramatically.

"Globally we've made great strides with reducing [measles] incidents by 80 percent since the year 2000," Goodson says. "But we do go through these periods where there are resurgences of measles. It happens and it's related to people not being vaccinated."

Goodson says there are three basic scenarios globally in which measles ends up with fertile ground to spread.

Don't see the graphic above? Click here.

The first: countries that don't have the health care infrastructure to consistently carry out immunization campaigns. Depending on the formulation, the vaccine needs to be refrigerated — transported and stored at between -58 degrees Fahrenheit and 5 F or between -58 F and 46 F. Either temperature range can be a challenge in tropical countries with spotty electricity. The countries with the lowest vaccination rates also tend to rank as some of the least developed in the world: South Sudan, Chad, Haiti, the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Sponsored

The second scenario feeding the spread of measles is civil strife. This applies to places like Syria and Venezuela that used to have strong immunization programs. Those systems fell apart due to war or social collapse. And Goodson says this doesn't just affect that individual country.

"That outbreak in Venezuela has gone on to spread throughout the region of the Americas infecting countries like Brazil, Chile, Peru," he says. "I could go on and on. Most of the countries in the region have now been affected by that outbreak."

The third scenario fueling outbreaks globally is when parents choose not to have their kids vaccinated even though vaccines are widely available. These people don't trust that the vaccines are safe or think there are too many vaccines or don't trust the health-care system in general.

In 2017 the botched rollout of a dengue vaccine in the Philippines (which turned out to make dengue infections worse in people who'd never had dengue previously) ended up causing vaccination rates to drop for other diseases including measles.

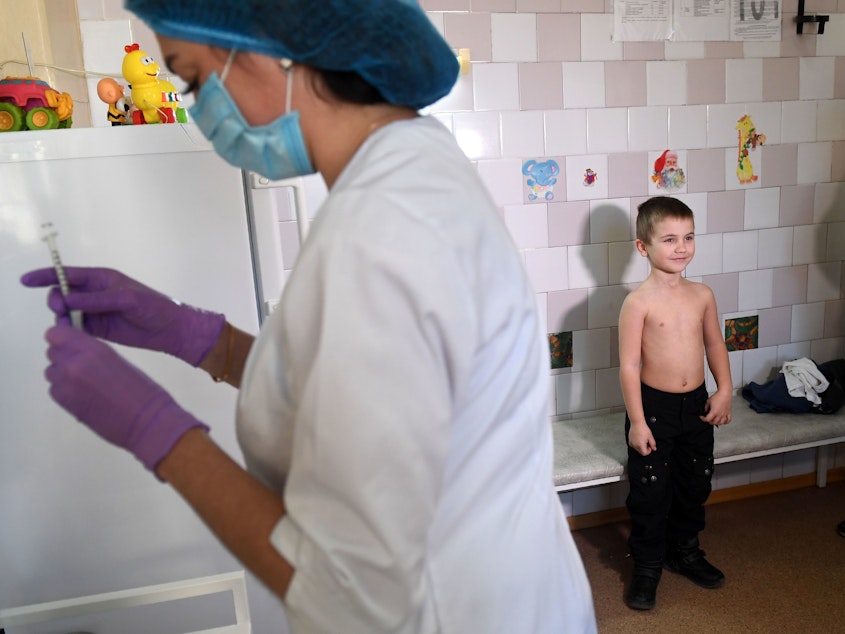

Dr. Robin Nandy, UNICEF's chief of immunization, says in some places like Ukraine several of these scenarios are playing out at the same time.

Sponsored

"Ukraine is a complex situation," Nandy says.

From March 2018 to February 2019, Ukraine recorded 72,408 measles cases, the most of any country in the world.

"They've had trust issues," he says about high levels of skepticism toward vaccines in Ukraine. "Also they've had system breakdowns, vaccine shortages that undermine community confidence toward the health service."

In addition, fighting between the government and pro-Russia separatists has caused some parts of the country to be cut off from others, disrupting lots of government services including vaccine delivery.

In 2016 according to WHO only 42% of kids in Ukraine were vaccinated against measles.

Sponsored

"It is not one cause or one determinant that causes low vaccination rates," Nandy says. "Each country is different. The Philippines and Ukraine are very, very different scenarios and there are very different reasons why kids in these countries are not vaccinated."

Nandy says the measles virus is a "super-spreader." It can linger in the air in a room or an airplane for hours waiting to find a new host. If exposed to the virus, 90% of unvaccinated people will end up infected.

But Nandy emphasizes that there's a super-effective vaccine to combat this super-spreader virus. He says the challenge for global health officials is to understand the complex social, economic and structural reasons that are keeping that vaccine from reaching everyone who needs it. [Copyright 2019 NPR]