WA activates alerts for missing Indigenous people – and forecasts more alerts overall

Washington state is the first in the nation to create a new missing persons’ alert specifically for Native Americans. It’s a victory for a movement that has worked to bring visibility to “Missing and Murdered Indigenous women.” They experience some of the highest rates of violence in the country.

But the first use of this new system reveals how complicated some missing persons’ cases truly are.

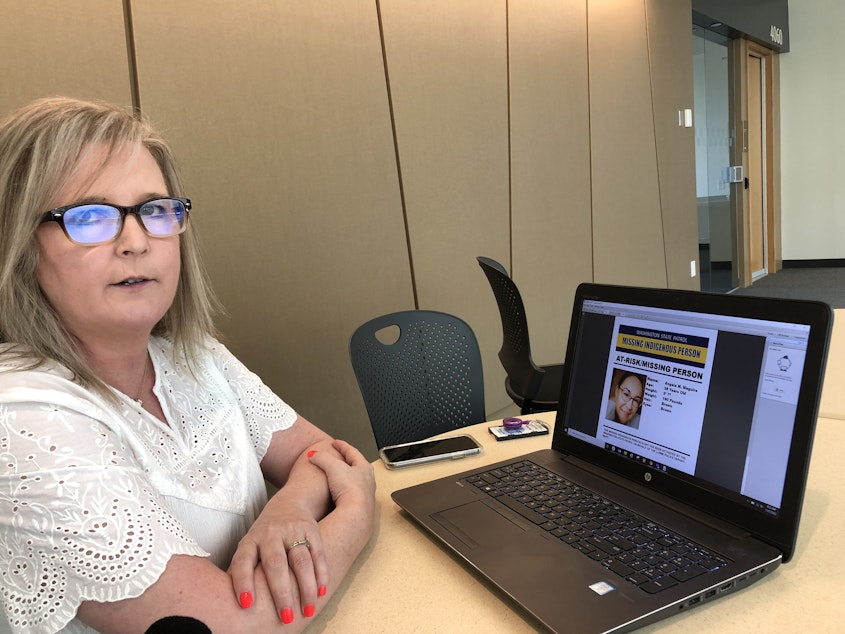

The new Missing Indigenous Person Alerts in Washington State took effect on July 1 – and within a few weeks, the system was activated. Law enforcement agencies, the media, and the public were asked to help locate a 38-year-old woman named Angela Maguire, who had last been seen in Ferndale in northwest Washington.

Angela Maguire’s mother is Lucy London. She filed the missing person report with Lummi Nation tribal police that triggered the alert.

The situation is complicated. Her daughter has bipolar disorder and has been in and out of the hospital. After being out of contact for about a week, London was concerned that her daughter’s mental health was deteriorating and that she might have left the area.

“She was blocking everybody except my youngest daughter, and she wasn’t posting anything on Facebook,” London said.

Lummi Nation police near Bellingham contacted the Washington State Patrol. There, the missing person alert coordinator Carri Gordon said thanks to a new software system that streamlines the process, she was able to issue an alert about Maguire to law enforcement and other subscribers in just a few minutes.

Sponsored

“We felt that it met the criteria and the agency’s requesting it because they felt like they needed to find her right away,” Gordon said.

Maguire’s story and photo were quickly picked up by local media. And by the next day, the alert had been called off. Maguire was reported safe. But authorities didn't contact her mother. London simply saw the news online.

“Nobody told me,” London said. “And I’m the one that reported it. I did talk to the police officer who took my report and he said, ‘I guess it’s a privacy issue.’”

Rosemarie Tom is a legal advocate with Lummi Victims of Crime and a point of contact between family members and law enforcement. She said they are still working on how to administer the new alerts, and as an advocate she can seek "additional outreach and fix those areas" for future cases.

But while police can report back to the family on the status of the alert, they can't offer very much information if the person reported missing is an adult.

Sponsored

London said she suspects her daughter may have contacted police and canceled the alert herself. Most recently, London said Maguire was staying at a local shelter and in limited contact with family members.

Patti Gosch is a tribal liaison with the Washington State Patrol. She said anyone over the age of 18 can tell law enforcement not to share their whereabouts. Gosch recently located a man whose family had been searching for him for decades. But the man told investigators he didn’t want his relatives to find him.

Gosch told the man’s relatives, “We have some really great news, but we also have some hard news. Because we have to respect his privacy.” The most she could confirm was that he was alive and safe.

But even if families aren’t always reunited, the new alerts for missing Indigenous people are getting the word out about a vulnerable population.

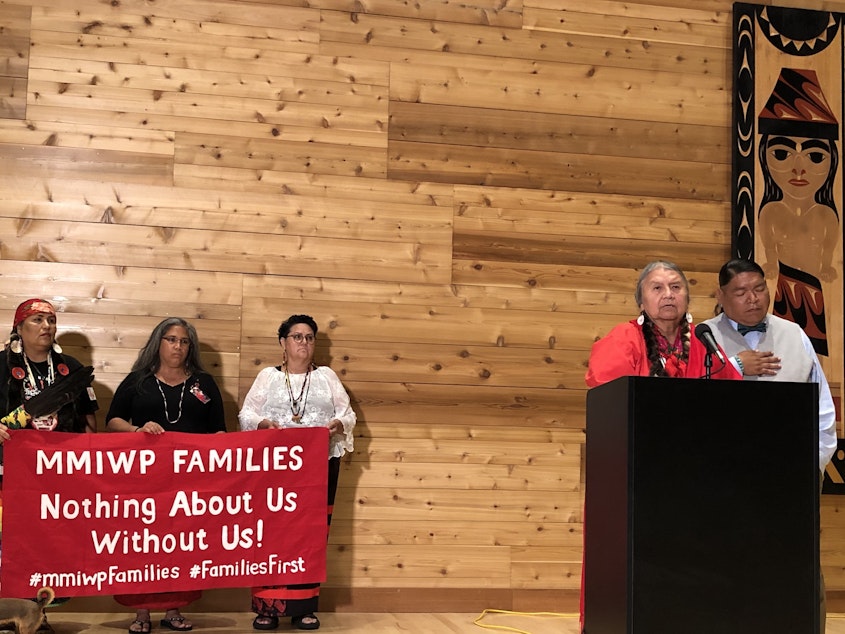

Patricia Whitefoot is a member of the Yakama Nation in Central Washington. She became an advocate for missing Indigenous women after her sister Daisy disappeared in 1987.

Sponsored

“It’s important to me that we have these kinds of systems in place,” Whitefoot said. “I have been thinking, what if that was in place when my sister went missing 30 years ago, what would that have done? It would have alerted everybody. I’m from a rural remote community and you don’t often know what goes on around you.”

Whitefoot is a member of the state task force on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People, which has been developing recommendations to collect data and understand the factors contributing to disparate numbers of Indigenous women who are reported missing across the state.

In the past, families said police have been reluctant to act on these disappearances. But Lucy London said when she contacted Lummi police about her daughter, the officer was immediately responsive.

“I feel that he put out a missing report right away because they know of my situation – that she is making unsafe decisions right now,” London said.

And the alert worked. London’s daughter was missing, and people acted with urgency to find her. But London said her daughter’s unstable situation highlights the distance between being found and being truly safe.

Sponsored

Back at the Washington State Patrol, alert coordinator Carri Gordon said the agency is making some major changes in the ways it handles missing person alerts in general. Gordon also administers Amber alerts for endangered children age 17 and under, and Silver Alerts for people over 60.

In the past, Gordon said the state only issued alerts if a vehicle was associated with the person’s disappearance (but local alerts could still be issued by the investigating agency). Vehicle information is still required to issue the alerts across cell phone networks and on highway billboards.

But Gordon said they are now issuing statewide alerts to subscribers and on social media even if, as in Maguire’s case, the person is believed to be on foot. That’s because the agency’s new software system streamlines the process to create these alerts.

Gordon said she expects the number of missing person alerts will increase overall. Her concern is that she doesn’t want the public to tune out (or opt out on their cell phones).

Sponsored

“The hope is that if the public knows we’re using it judiciously and only in those cases where the person’s life is in imminent danger, that we can engage the public,” Gordon said.

Gordon added that the public could see two changes in the coming months. One is the ability to geo-target missing person alerts to cell phones just in the area where the person disappeared. Another will be the ability to include a hyperlink in the cell phone alerts, so people receiving them can click to see the photo of the missing person.

Gordon said the state has normally seen about four Amber alerts each year, until a disturbing new trend brought about an increase in 2021: people stole more running vehicles with children in the back seat. She said that contributed to a total of nine Amber alerts in 2021, and another four so far this year.

“It’s not just a Washington issue, it’s national,” Gordon said. “It’s just a freak thing that just started happening this past year or two, is that kids are being left in running vehicles that are stolen.”