This law said teachers could hurt kids to 'correct' them in Washington. One boy shared his story to change that

A longstanding law — changed this legislative session — said teachers could use physical discipline as long as the violence was "reasonable and moderate" and caused only "transient pain or minor temporary marks."

That's despite the state having passed a law banning corporal punishment three decades ago.

When Julianna Rigg Hillard and her husband Dustin complained to the school principal at West Woodland Elementary School in Seattle that their 6-year-old’s teacher was routinely, painfully yanking their son’s ear when he got math problems wrong — and, one time, grabbed their son by the neck — they were startled by the response.

"The principal said, ‘But he used an open fist.’ And we were both gobsmacked," Julianna Rigg Hillard said.

The principal and police both pointed to a state law on permitted use of force against children. It was never changed when corporal punishment was outlawed in 1994. The use of force law still held teachers to the same standard as parents, and said teachers could use physical discipline "for purposes of restraining or correcting the child."

Discipline deemed unreasonable under the law includes throwing, kicking, burning, suffocating or cutting a child, or striking a child with a closed fist.

Sponsored

"I don't think any parent sends their child to a public school and expects that to be the threshold for how a teacher is allowed to touch their child's body," Rigg Hillard said.

The Rigg Hillard family, including their son, who's now in sixth grade, worked with state Rep. Sharon Tomiko Santos (D- Seattle) to change the outdated law.

2 mins

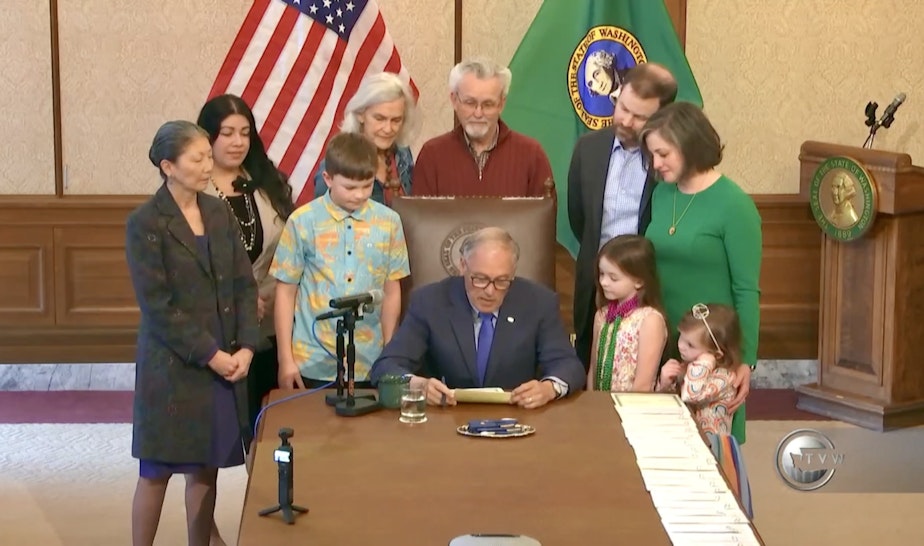

Washington Governor Jay Inslee signs HB 1239 into law with the Rigg Hillard family present on March 25, 2024.

2 mins

Washington Governor Jay Inslee signs HB 1239 into law with the Rigg Hillard family present on March 25, 2024.

"I was quite taken aback when I came to find out that there was this criminal defense that specifically cited teachers in a different portion of the code," Santos said.

As the longtime chair of the House Education Committee, she said her work is typically focused on civil code, not criminal code.

Sponsored

The new law passed this year removed teachers from the list of caregivers who can physically discipline students.

The law does maintain teachers' ability to physically restrain children in accordance with state law, but "only when a student's behavior poses an imminent likelihood of serious harm." That was a compromise, Santos said.

"We were not able to completely eliminate [the legal use of force by teachers], which was my initial desire," she said.

A KUOW investigation in 2020 found that the West Woodland teacher, Martin McGowan, had been formally and informally reprimanded at least five times between 2005 and 2019 for pulling first-graders by the ear, grabbing them by the neck hard enough to leave red marks, slapping them on the hands, and mocking them in front of the class — in some cases, about their learning disabilities.

Following KUOW’s reporting, other families reported that McGowan was still physically and emotionally abusing children in his current classroom. He was fired after a district investigation.

Sponsored

RELATED: ‘My first-grade teacher was my first bully.’ More allegations surface against Seattle teacher

The Rigg Hillard family, including all three kids and their grandparents, made many trips to Olympia. They testified before the state legislature, along with other proponents of the bill, and watched every floor vote. That meant late nights for the kids, and some missed school — all worth it, Rigg Hillard said, to learn firsthand how a bill becomes a law, and to close a painful chapter in their lives.

"It was just so deeply moving as a parent to watch our child, who had been harmed, use his voice to actually make a change that's going to hopefully keep kids safer at school," Julianna Rigg Hillard said.

Now, Rigg Hillard said, "Our kids know that speaking up makes a difference. Hearing that over and over again, from dozens of legislators, was really very healing."

The new law, which garnered broad bipartisan support, includes a way for citizens to file complaints about K-12 school staff misconduct or other legal or policy complaints directly with the Governor’s Office of the Education Ombuds. It also introduces a code of educator ethics to be determined or developed by the state Professional Educator Standards and Paraeducator Boards by September 2025.

Sponsored

The law goes into effect June 6.