What The 1918 Flu Pandemic Teaches Us About The Coronavirus Outbreak

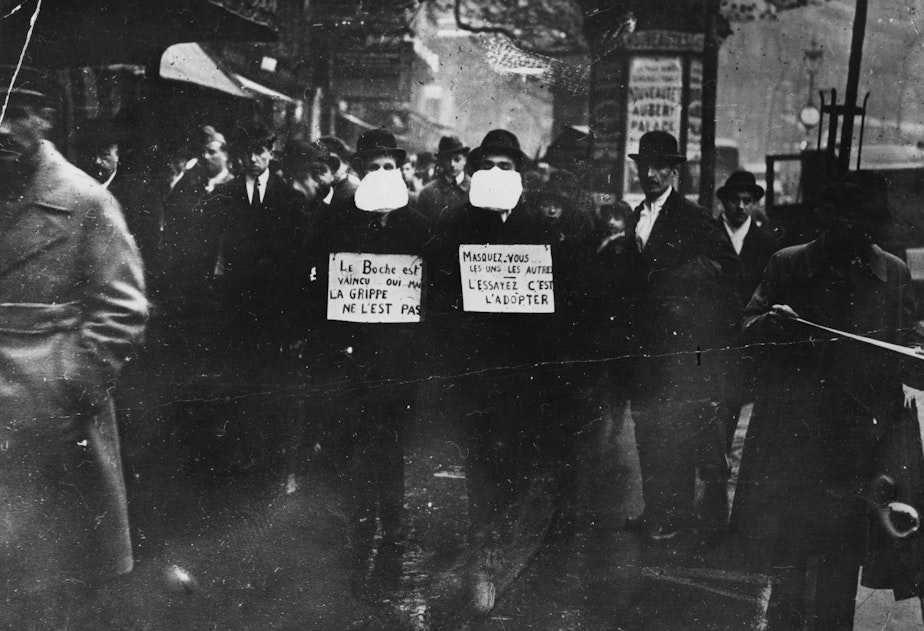

It’s been more than 100 years since all of humanity has had to respond to a global pandemic on the scale of coronavirus. We’ll take a deep look at the origins, responses and lessons of the flu pandemic of 1918.

Guests

John Barry, professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. Author of “The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History.” (@johnmbarry)

Jack Beatty, On Point news analyst. (@JackBeattyNPR)

Interview Highlights

Sponsored

There were various responses to the 1918 flu pandemic between different cities in the United States. Can you tell us what Philadelphia did or didn’t do differently?

John Barry: “Because we were at war, the national public health leaders basically lied to the public. They said things like, ‘This is ordinary influenza by another name.’ Or, ‘You have nothing to fear. Proper precautions are taken,’ so forth and so on. This was echoed by local leaders in many cities, Philadelphia being a prime example. So they had a big Liberty Loan parade scheduled, which they declined to cancel, although all the medical community urged them to. And 48 hours later, just out like clockwork, influenza exploded in the city.”

Weren’t 300,000 people expected to come to this parade?

John Barry: “Something like that. And health results were lethal. Later, they did institute what we call social distancing and closed everything down. Restaurants, churches, services. But it was too late because the virus had already become widely disseminated in the city. And Philadelphia had one of the worst experiences in the pandemic. I think roughly 14,500 people in Philadelphia died. One of the lessons is not just social distancing, but you have to implement these measures early. If you don’t, if you wait until a lot of people are sick and it’s widely disseminated — the virus — it’s way too late and it will not have significant impact. But if you do do it early — if you get widespread compliance — these measures do work.”

On President Wilson’s response to the influenza

Sponsored

John Barry: “He never released any statement about influenza whatsoever. The federal government did next to nothing. Of course, we had a different society then. But everything was up to local leadership. And that’s one reason why we got such varied responses. A lot of it is also just random luck. In some places, the virus seemed more lethal than others. The earlier cities that were hit were hit much harder. And the virus seemed to attenuate a little bit over time. So if got hit later, you were in better shape. And if you got sick in the same city later in the epidemic, you were in better shape. It wasn’t because medical care improved, medical care deteriorated. At first, it was nothing they could do anyway except supportive care. And second, by later in the outbreak, particularly in the same city, medical care was totally exhausted and overwhelmed. So the virus was the chief determinant of what was going on.”

On whether President Woodrow Wilson had the flu when he was trying to negotiate the peace treaty for World War I

John Barry: “Quite definitely. It was rampant in Paris at the time. He had 103, 104 degree temperature, violent coughing. … One of the unusual complications of influenza was mental disorder, even to the extent that the people Oliver Sacks wrote about in Awakenings. Very strong hypothesis that they had suffered from influenza. It was a disease called encephalitis lethargica, which occurred after influenza a few years later and then disappeared. Sequel to influenza. And Wilson got it. He had been standing absolutely firm in the peace conference prior to getting sick.

“After he got sick, people were saying that they had never seen him like that. He was paranoid. He couldn’t remember an hour later, what had been discussed an hour before. He was physically weak. And in that frame, he went back into a room with just a handful of other leaders, particularly Clemenceau, whose nickname was ‘The Tiger’ and was much more forceful. And Wilson ended up caving in and abandoning basically all the principles that supposedly the U.S. had gone to war for. John Maynard Keynes called him ‘the greatest fraud on Earth.’ So, you know, might he have caved in regardless? You know, it’s possible.”

From The Reading List

Sponsored

The New York Times: “The Single Most Important Lesson From the 1918 Influenza” — “In 1918, a new respiratory virus invaded the human population and killed between 50 million and 100 million people — adjusted for population, that would equal 220 million to 430 million people today. Late last year another new respiratory virus invaded the human population, and the reality of a pandemic is now upon us.

“Although clearly a serious threat to human health, it does not appear to be as deadly as the 1918 influenza pandemic. But it is far more lethal than 2009’s H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic, and the coronavirus does not resemble SARS, MERS or Ebola, all of which can be easily contained. About 15 years ago, after yet another global contagion — the so-called bird flu — emerged in Asia, killing about 60 percent of the people it infected and threatening a catastrophic influenza pandemic, governments worldwide began to prepare for the worst.

“This effort included analyzing what happened in 1918 to identify public-health strategies to mitigate the impact of an outbreak. Since I had a historian’s knowledge of 1918 events, I was asked to serve on the initial working groups that recommended what became known as non-pharmaceutical interventions, that is, things to do when you don’t have drugs.”

Vox: “The most important lesson of the 1918 influenza pandemic: Tell the damn truth” — “‘We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.’

“That was President Trump’s response when asked by a CNBC reporter on January 22 whether he was worried about the coronavirus. Almost two months later, with the threat too large to ignore, the president’s tone has shifted dramatically (even as his press briefings continue to be models of incoherence and inaccuracy).

Sponsored

“The contradictory messages about the virus, and the dishonesty motivating them, is dangerous right now. Refusing to tell people the truth will cost lives because it undercuts our efforts to flatten the epidemic curve with practices like social distancing. It also erodes the public’s trust in government — and that’s a huge problem.”

The Washington Post: “Trump is ignoring the lessons of 1918 flu pandemic that killed millions, historian says” — “The first wave wasn’t that bad. In the spring of 1918, a new strain of influenza hit military camps in Europe on both sides of World War I. Soldiers were affected, but not nearly as severely as they would be later.

Even so, Britain, France, Germany and other European governments kept it secret.

“They didn’t want to hand the other side a potential advantage. Spain, on the other hand, was a neutral country in the war. When the disease hit there, the government and newspapers reported it accurately. Even the king got sick.

“So months later, when a bigger, deadlier wave swept across the globe, it seemed like it had started in Spain, even though it hadn’t. Simply because the Spanish told the truth, the virus was dubbed the ‘Spanish flu.'”

Sponsored

The New Yorker: “An Economic-History Lesson for Dealing with the Coronavirus” — “When I put this question to Barry Eichengreen, a professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, on Tuesday, he said that he couldn’t think of one. Something that originated as ‘supply shock’ in China, just a couple of months ago, has morphed into an unprecedented economic shutdown, remarkable not just for its size but for its rapidity.

“Eichengreen, who specializes in economic history and is the author of more than a dozen books, including a highly regarded history of the Great Depression, said that he is working on the assumption that consumer spending will fall about thirty per cent in the second quarter of 2020. That would be unprecedented.

“The Great Depression, which began after the stock market crashed in October, 1929, was wrenching and disastrous, of course. But Eichengreen pointed out that it developed more gradually than the coronavirus shock. ‘The production of goods and services fell by about a third, but over a period of three-plus years,’ he said. ‘Industrial production fell by half, but, again, over a period of three years. The unemployment rate rose to about one in four, but over four years. Now what we are talking about is the possibility that the unemployment rate could shoot up very dramatically in a very short period of time.'”

This article was originally published on WBUR.org. [Copyright 2020 NPR]