When anxious kids won't go to school, what should parents and schools do?

Most kids have days when they just don’t feel like going to school. But what happens when kids straight-up refuse to go?

Thomas is 15.

He develops games, creates electronic music and makes digital art.

At home in Seattle recently, he flipped open a laptop to show off some of his work.

“I use mathematical equations to generate three-dimensional fractals,” he said, scrolling through a gallery of glowing, geometric dreamscapes.

We're only using Thomas's middle name to protect his privacy.

Sponsored

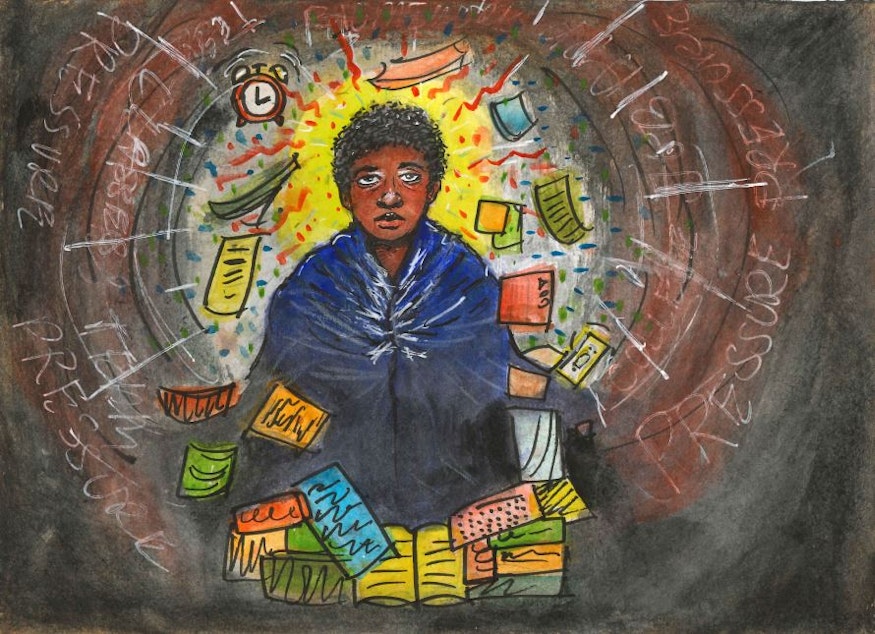

Academics have come easily for him, but school has not. It began to make him anxious in elementary school: getting there at the right time, not too late, not too early - and all of the homework, which felt like mountains of redundant busywork. By ninth grade, Thomas was so stressed by school that he’d sometimes need a five-hour nap to recover — right through dinnertime.

The anxiety mounted until it gave way to depression. As depleted as he felt each day, his mom marveled at his ability to drag himself out of bed and get to school.

Sponsored

By his first year of high school, though, he started staying home some days.

“He was saying, almost, like, ‘I’ve run out of my ability to push through this,’” his mom said. “Which was also a really good indicator for us: like, okay, this has shifted now into something much more significant.”

Psychologists call this “school refusal,” and say reports are on the rise.

Jennifer Tininenko, who co-directs the Child Anxiety Center at Evidence Based Treatment Centers of Seattle, said that after getting calls about school refusal every day, the center developed a program dedicated to it.

Tininenko said it’s not clear why they’re seeing more cases of kids refusing to attend school. There’s not much research on this phenomenon.

Sponsored

Tininenko said in her clinic, they have to tailor a return-to-school strategy for each family, because each situation is different. The first step is figuring out why.

Tininenko said for some kids, it feels good to stay home with a parent, even if their parent spends much of the time trying to coax them back to school.

“That is very powerful attention that, when kids are doing okay, they may not get that amount of parent attention,” she said.

Or kids are avoiding a bully, or a particular social dynamic.

But at least half of the time, Tininenko said, it’s due to a mental health condition – often anxiety, depression, or both.

Sponsored

She said technology often plays a role.

Kids will say to her: “I wake up and I don't feel very well, and I'm tired, and I think about all the things about school that are kind of hard, and I think well, I could just take a mental health day.”

Tininenko said kids tell her that when they stay home, they soothe themselves by playing video games, or doing something else online, where they know they'll feel okay.

Grown-ups might remember sick days home from school as a dreary selection of TV game shows and soap operas.

Tininenko said technology means kids today have no trouble staying entertained. They can binge-watch their favorite shows – and keep up their social lives by texting their friends all day.

Sponsored

But the longer kids avoid school, the more daunting their return feels.

For Thomas, all that extra homework became overwhelming, even after missing just a day of school.

“Teachers being, like, ‘Oh, hey, there’s more work you have to do now, and here’s yesterday’s homework, please fill it out by the end of this period,’” he said.

By last December, Thomas was missing a lot of school. His family tried everything to battle his anxiety and depression, including medication and therapy.

But when Thomas did go to class, teachers told him he was in danger of failing if he didn’t catch up on the work he’d missed.

Sponsored

His mom said his psychiatric nurse practitioner had an idea, and wrote a letter to his teachers.

According to Thomas’s mom, the nurse practitioner wrote, “I know it’s completely unconventional, but his family and I have all agreed that it’s okay for him to fail.”

The nurse practitioner explained that Thomas had been out of school because of a mental health crisis.

She asked the school to forget about grades, and catching up, and to let Thomas try to re-engage with school.

Thomas’s mom assumed the response would be resounding empathy. Instead, she said, school staff replied that they didn’t see how that plan could work.

“The most concerning response we got from one teacher was, ‘I don’t think it’s appropriate for him to be at school if his goal is not about grades and performance,’” she said.

School districts in the region vary in how they approach school refusal.

Some told KUOW they treat it as truancy. Others take a holistic approach, and work with parents and mental health professionals to design a plan to ease kids back into class.

Tininenko said it’s key for parents and schools to work together on school refusal, whether students have been gone a few days – or a few years.

She recommends schools designate a point person who gives zero guilt trips.

“That person will say ‘Welcome back, and let's figure out how to tackle this mountain of assignments,’” she said. For students, she said, “the willingness generally is there. It's just that anxiety or some other block is making it difficult for them to be there.”

After being in and out of school for a year, Thomas plans to return to school full-time this fall.

He’ll take community college classes through the Running Start program.

He hopes starting fresh will reduce his anxiety – and make going to class feel exciting, not daunting.