Will A Massive Effort To Secure The 2020 Vote End Up Superfluous Or Not Enough?

Americans are preparing more than ever to safeguard voting as the nation looks ahead to the Democratic primaries and the general election next year.

What no one can say for certain today is whether all the work may turn out to be superfluous — or whether it'll be enough.

National security officials have been clear about two things: First, that the Russian government attacked the 2016 election with a wave of "active measures" documented in prosecution documents and the final report of former Justice Department special counsel Robert Mueller.

And second, that those measures have never stopped and that interference is likely in coming elections.

With that understanding, the United States has spent hundreds of millions of dollars since 2016 to change practices at every level of government.

Sponsored

A lot has changed

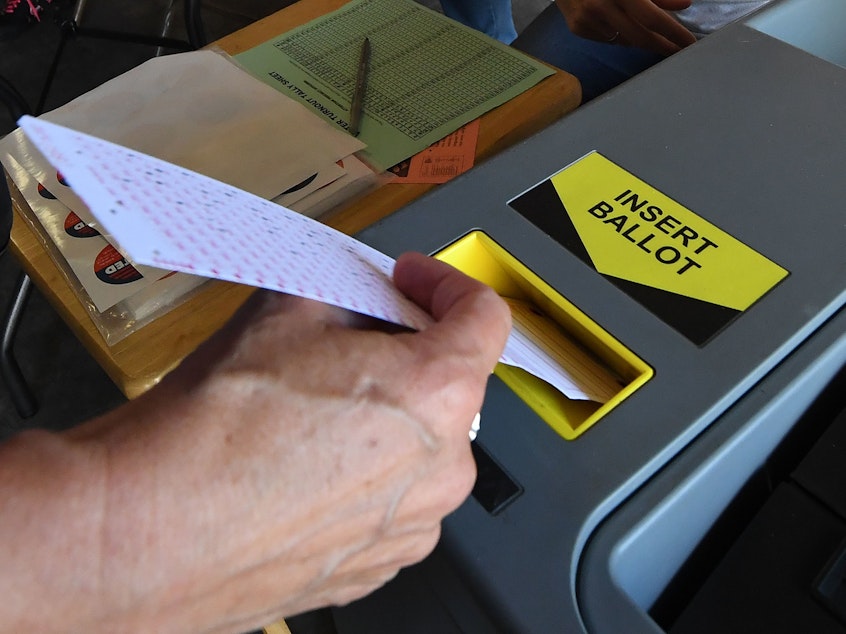

More states are buying more voting machines that yield paper ballots to hedge against cyber-dangers and make it easier to audit results after the fact.

The Department of Homeland Security is working more closely than ever with state and local elections officials to raise awareness about cybersecurity dangers and new practices.

And the national security establishment says it has increased the tempo of its operations, many of which remain clandestine, to dissuade foreign governments such as Russia's from attempting to run a playbook like that of 2016.

Influence specialists launched a wave of cyberattacks against political targets across the United States and released some of the material they stole to embarrass their victims, mainly Democrats.

Sponsored

Meanwhile, they also sought to amplify agitation online with false accounts, disinformation and the now-infamous "fake news."

Facebook, Twitter, Google and other Big Tech companies say they're remaking their own internal practices to curtail a foreign nation's ability to use their services to spread disinformation or aggravate political differences among users.

Representatives from those companies met last week with officials from the FBI, DHS and the intelligence community to compare notes about election security, one of Facebook's top cybersecurity officers said.

And that followed the companies' decisions to reveal what they've called state-sponsored influence campaigns in real time, in the latest example of shutting down accounts that had been connected with a government information operation.

If that keeps up through 2020, users around the world could get a much different understanding about which governments might be trying to achieve which aims through fake accounts, disinformation and agitation.

Sponsored

The name of the game

Will it all be enough? Security experts and supporters of further changes say the news is not all good.

For all the new voting equipment expected to be fielded by Election Day 2020, roughly 16 million Americans are expected to cast votes that leave no paper record, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University.

Many machines also likely will continue to run on obsolete software, further complicating the potential cybersecurity exposure. One hacker who experimented with an election machine at a conference in Las Vegas told NPR he wouldn't trust the equipment's software to run his toaster.

There's also no guarantee that an influence campaign targeting the United States in 2020 might look like the last big one.

Sponsored

It could rely more on spreading sophisticated fake media than on the past campaign's comparatively simple posts and memes. Its political dimensions could be different in terms of the candidates or parties who stand to benefit. The nations involved could be different too.

President Trump already has charged China with trying to make a case against him among Americans because Beijing has wearied of the trade war with Washington. The Chinese have sponsored some overt messaging that makes plain their unhappiness — will that include a clandestine effort, too?

In 2016, Russia's interference campaign was aimed at helping Trump and hurting his Democratic rival, Hillary Clinton. Since then, Russia and China have grown strategically closer. Russia also has become a big booster for China in its official messaging, according to one report from the Alliance for Securing Democracy.

Looking ahead to prospective interference in 2020 requires asking whether these new dynamics might prompt Russia to sit out another big wave of active measures, whether it might join China in opposing Trump, if Beijing in fact does — or whether these allies could pick opposite sides in the U.S. election.

Trump and his allies have emphasized how many nations other than Russia are involved with trying to influence the U.S.

Sponsored

Fighting the next war

The names of the players might not be the only difference in 2020 as compared with the earlier election. The techniques might be different, too.

For example, Paul Barrett of New York University's Stern Center for Business and Human Rights warned in a report that influence-mongers might make greater use of different social platforms, including Instagram and WhatsApp.

Katherine Charlet and Danielle Citron of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace wrote in a commentary that they worry about high-quality fake video and audio. One fear is these fake media could begin to circulate with corrosive effects on Americans' confidence about what they see and hear.

And the Department of Homeland Security has said it wants to help elections officials safeguard against ransomware — attacks in which governments lose access to their own networks unless they pay the attackers.

Ransomware has crippled some American cities and although it hasn't yet disrupted an election, Department of Homeland Security officials worry that state, county or other elections systems could be a future target.

If the outlook is uncertain, what is also clear is that attitudes across the board have changed, too. Political campaigns, federal officials, state and local supervisors and many voters are going into 2020 with their eyes open in a way that's seldom been the case for U.S. elections.

That may not mean the coming months necessarily run smoothly. Lt. Gen. Stephen Fogarty, head of U.S. Army Cyber Command, was asked about the outlook for his Russian counterparts. He told an audience in Washington that he expected the back-and-forth in cyberspace to be energetic.

"It's going to be pretty sporty, actually," Fogarty said.

Pam Fessler, Miles Parks, Tim Mak and Ryan Lucas contributed to this report. [Copyright 2019 NPR]