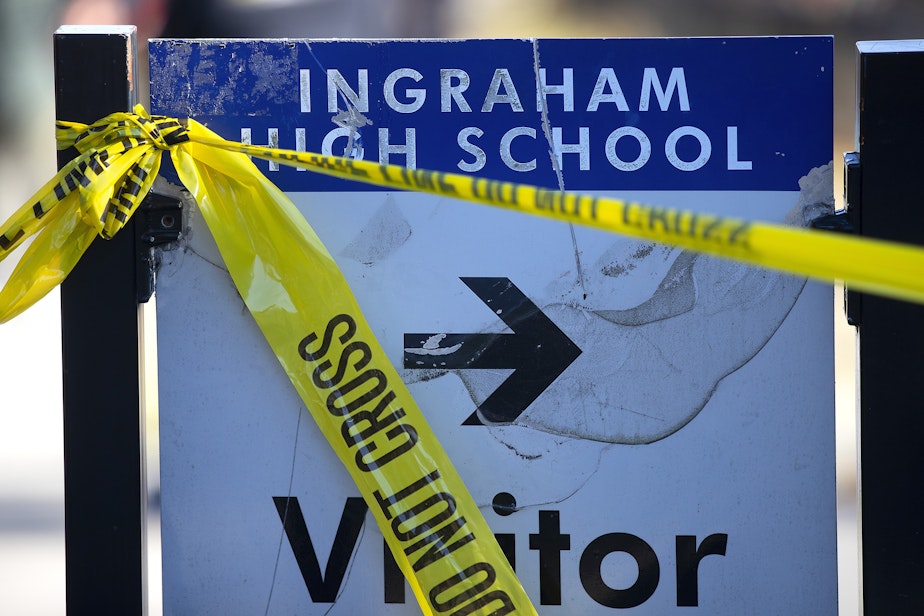

A year after a shooting at Seattle's Ingraham High, students remain traumatized — and they want change

I

t’s been a year, but Kalli Dahlberg doesn’t think she’ll ever forget the morning of Nov. 8, 2022.

Her second period social studies teacher was wearing the same “Vote!” T-shirt he wears for every Election Day and talking about the Electoral College, when she heard gunshots just outside her classroom.

Dahlberg remembers her teacher crouching and running to the door to lock it from the outside. But as she reflects on that day, standing outside school on a windy November day, Dahlberg said what really sticks with her is the look of “absolute terror” on her friend’s face.

“I had a lot of moments that day where I thought, ‘Oh my God, this is happening,’” she recalled through tears. “That was one of them — just, ‘Oh my God.’ That wasn’t lockers. That was a gunshot. This is happening now.”

Sponsored

Later, Dahlberg crawled to the corner of the classroom farthest from the door. As her classmates texted their families and friends, Dahlberg realized she’d left her phone across the room. She could barely remember her mom’s phone number, but she borrowed her friend’s phone to text her goodbye — just in case.

“It was obviously a very traumatic situation,” she added. “At least for me and some other people in my class… we thought we were next.”

Outside Dahlberg's classroom, 17-year-old Ebenezer Haile had been shot and killed by a fellow student in that hallway, leaving a community reeling from a tragedy that has become all too common in schools across the nation.

RELATED: About the gun that killed a boy at Seattle’s Ingraham High School

Sponsored

As Dahlberg and other Ingraham students reflected on the year since the shooting and the upcoming one-year anniversary, they said trauma and grief from the shooting continues to haunt them.

Students are still on edge at school and little things can rattle them — like sitting in a dark classroom, fire alarms going off, the sound of a locker being slammed shut, or a track and field pistol going off to mark the start of a race.

“Here we are a year later and, I mean, for everyone it’s completely different,” Dahlberg said. “But we’re living in the aftermath, and that’s kind of the only option we have.”

RELATED: A tearful vigil and demand for change: Family and friends gather to honor Ingraham shooting victim

Seattle Public Schools officials have drawn links between the shooting and student wellbeing, as they appealed for more resources over the last year.

Sponsored

In an application for a nearly $500,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Education’s School Emergency Response to Violence Initiative this summer, the district shared data showing grades and attendance dipped at Ingraham since the shooting. They said more students were getting into trouble, and were struggling with depression and anxiety.

Ingraham senior C Makar-Wituki said he struggled for months after the shooting, though he wasn’t as close to it as Dahlberg had been. But luckily for Makar-Wituki, he already had a therapist he could turn to for help.

“My grades got worse. I got very ill,” he said. “I already had mental health problems and they got much worse. My appetite was completely gone.”

And he knew he wasn’t alone. Makar-Wituki noticed his classmates were absent from school more often and seemed “more fragile.”

Sponsored

In a statement Tuesday, the district said over the last year it’s been “dedicated to taking a comprehensive approach to addressing trauma at Ingraham while implementing enhanced security measures.”

A day after the shooting, Superintendent Brent Jones launched a districtwide safety and security initiative. Since then, the district said it has upgraded locks across the district so they can be activated inside classrooms, improved security camera systems, rolled out new safety signage, and expanded counseling services and staff training programs.

District officials also successfully secured that federal grant from the education department. Those funds have been put toward the hiring of another security specialist at Ingraham and administrator who plays a critical role in overseeing school safety measures, plus more mental health support for both students and staff.

And the district got another nearly $228,000 grant from Seattle’s Department of Education and Early Learning to finance a new full-time social worker, contracts with outside organizations for mental health and substance use support, and a new restorative practices initiative.

Students say they appreciate the district’s progress — and they’re proud they obtained $4.5 million from the City of Seattle for a mental health pilot program at several schools including Ingraham — but it’s not enough.

Sponsored

“We are a hurt community,” Makar-Wituki said. “The school did not adequately show that they cared about our community.”

Makar-Wituki founded a student union at school soon after the shooting as a way to advocate for student needs.

And still, a year after the shooting, they have a long list of demands — like more staff training, better lockdown procedures, and more counselors in school who Makar-Wituki believes could help prevent incidents like the shooting from taking place, rather than serving as a “Band-Aid solution.”

Ingraham student Elliot Franklin-Bihary struggled after the shooting, largely from their experience hiding and the hours-long reunification process in the school auditorium. Franklin-Bihary was also grieving after a friend died of an overdose the week before.

But like Makar-Wituki, Franklin-Bihary feels lucky to have had access to a therapist in the aftermath of those traumas — something they know many of their Ingraham classmates do not have.

“I would say the majority of kids at the school don’t have access to a therapist,” Franklin-Bihary said, “or access to a good therapist, or don’t have access to the correct type of therapy, or don’t have access to therapy they can get transportation to.”

“It took me years of different therapists to actually find a type of therapy that can help me with my various issues,” they added.

That’s why Franklin-Bihary and Makar-Wituki, as members of the Seattle Student Union, are also pushing the city to allocate $28 million to properly finance mental health services at all public schools.

But what’s really at the heart of all these issues for students is how poorly they feel communication has been handled — both during the shooting and in the months since.

Many students feel district and city leaders have failed to fully include them in conversations about safety, Dahlberg said, and they seem to dismiss their trauma.

“It’s something you’ll never ever move on from,” Dahlberg said. “Not that you should, but that’s why it’s so hard. Being one year later is like, the father we get from it, you’re expected to heal and move on.”

There are a few specific changes students want for Ingraham.

One is to erect permanent memorials in the school for Haile and three other Ingraham students who died last year.

Although the school replaced some tiles in the hallway where Haile died, Franklin-Bihary said they’re lighter than all the other tiles and they serve as a constant reminder of what happened.

“We can still tell from the floor exactly where he died, but there isn’t a plaque or a memorial anywhere for him,” Franklin-Bihary said. “It feels so disrespectful to this student that he was murdered in our school building and to all the people that were his friends and his family who don’t get any space to remember him.”

Another change they want to see is the replacement of the track and field starter pistol. But Makar-Wituki said staff have left it to the students to figure out raising about $27,000 to replace the school PA system.

Ingraham's principal Martin Floe declined a request for comment and directed the reporter to district administrators.

“We shouldn’t have guns to start track meets to begin with, but like, in order to replace them, we have to fix it?” Makar-Wituki said. “That’s crazy.”

For some students, pushing for these changes is a way to cope and look for closure.

Dahlberg, the student who pulled her friend under her desk with her, will graduate this school year. But she expects this issue is something she won’t let go of for a long time.

“A part of me is never going to leave that room or that moment, and I just have to learn to live with that,” she said. “But I don’t have to accept it for people like my young cousins — for people who will grow up and take a part of this with them and have to live with it.”

She added: “At one point, enough has to be enough.”