Elders caught in Seattle's coronavirus isolation remind us: 'Bad times don't last'

For Mary Hanson, the break in her coronavirus isolation came in the form of a hamburger.

“We got a Kidd Valley burger, oh my God, that was so good,” she said.

Hanson is 79 and lives on her own in Shoreline. Like many older people in the Seattle area, she’s having to cope with isolation during the coronavirus pandemic as they find themselves cut off from friends and family.

“The routines have come on gradually,” she said.

Most recently her Monday night movie was replaced by a drive with her daughter – and that burger.

Hanson is a retired nurse, but jokes that she’s technology impaired. She's spending most of her time alone. So like many people, she’s had to learn some new skills.

“Now I am Facetiming, and Viber-ing, that’s what I do with my daughter who lives in Britain,” she said.

Sponsored

And Hanson is a churchgoer so she’s learned to watch her priest hold mass via Youtube.

Hanson’s life was directly shaped by the last big pandemic; her grandfather died of the flu in 1918.

“He was 27 years old. He left six children. And my father was adopted out,” Hanson said.

She said it might take a decade to know all the consequences of what we’re going through, and she doesn’t know if she’ll experience all of that. But she does feel hopeful right now.

“I have been through very, very hard times,” she said. “But I’m also an optimistic person. I have resilience, I know that. I’m a survivor.”

Sponsored

Over in Seattle's Central District, Reverend Harriett Walden is also coping with the quarantine at home. But even then, she said she feels surrounded by family and community.

“I talk to all my kids every day,” she said. “And then people always ask if I need anything.”

But she says she doesn’t mind being alone.

Sponsored

“I know how to be by myself and not be lonely, because I was raised as an only child."

Walden is not retired. She hosts a radio show, and co-chairs Seattle’s Community Police Commission. She misses being out and about.

“I love being on the road. I love just MOVING,” she said.

One of her favorite outings is the tulip festival in Skagit Valley, which would in a normal year be approaching this week. Instead, she’ll post pictures of tulips on Facebook this week. Anything to give people beauty and hope.

“As we say in the black community, bad times don’t last always and we have a song that says, ‘the storm is passing over.’ I mean, we believe that,” she said.

Sponsored

Walden says the pandemic is testing society’s response to vulnerable people. “This will be the measure of our humanity,” she said.

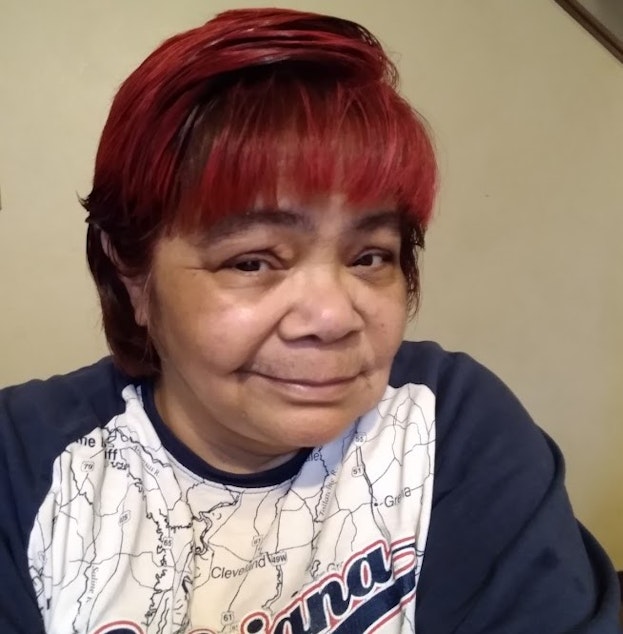

Gina Owens is another community activist who is now confined to her apartment in the Central District, though she tries to stay connected using her computer.

Owens herself is high risk due her health. But she can’t isolate completely -- she lives with two of her grandchildren, ages 16 and 21.

They try to keep apart.

“But I have a hard time with them not wanting to be away from me,” she said. “They’ll come downstairs and lay their heads on my shoulder and say, I just needed to be by my grandma.”

Sponsored

She said they’ve also been bored with the isolation.

“The challenges are there, we just have to kind of muddle through,” she said.

Owens said they livened things up last week by dyeing their hair together. It’s now a wild shade of red.