How Seattle could raise more money by lowering most business taxes

Seattle leaders want to give the city’s business tax system a makeover.

Wealthy companies like Amazon could end up paying more.

And small businesses, like restaurants, could end up paying nothing.

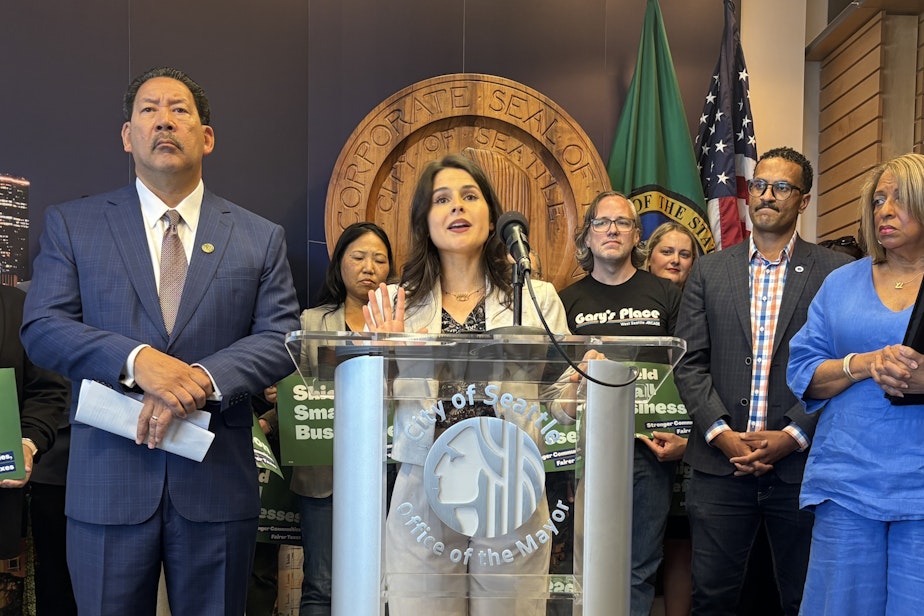

Mayor Bruce Harrell and City Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck unveiled a new plan to tax businesses. It's a "progressive tax," meaning it shifts more of the tax burden to wealthy businesses.

The tax plan now goes to the City Council for consideration. If passed, the measure would go to the November ballot, where voters would have the final say.

It’s understandable why the policy might confuse some people. Is the city raising taxes? Or lowering them?

Rinck says it depends on how wealthy the businesses are.

"From a policy perspective — and we’ll check on this with the city archives — but this might be the biggest tax break on small businesses in the city’s history," she said.

Sponsored

Even with that tax break, Rinck expects higher taxes on wealthy companies will more than make up for it.

In fact, city staff say it should bring in around $90 million more per year.

The Seattle Metro Chamber of Commerce praised the tax break, but condemned the tax increases, referencing high vacancy rates downtown. Chamber CEO Rachel Smith said the city should pass the tax breaks but fund it out of the city's own money.

Over the next two years, Seattle faces a $241.5 million revenue shortfall. That's after it's cut spending by eliminating vacant positions, forgoing tech upgrades, and banning non-essential travel. And that's before we know how many of the Trump administration's reductions in federal spending for Seattle will survive court challenges.

RELATED: As countries lob tariffs, this small Seattle business hunkers down

Sponsored

The B&O tax reform measure received no love from the Downtown Seattle Association, whose CEO Jon Scholes called the plan "boneheaded."

Sponsored

But the idea has won the full support of Mayor Bruce Harrell, who is running for reelection and has faced low approval numbers.

That decision has surprised many, since Harrell has generally been much more cautious about taxing companies like Amazon. But Harrell told reporters, labor organizers, and small business organizations at a press conference Wednesday that President Trump's numerous attempts to cut spending in cities like Seattle have forced him to take a long look at which companies are pulling their weight.

"One reason why I want a healthy business environment, for large businesses and small businesses and everything in between, is because they employ people," he said. "But they have a corporate social responsibility value that I have to see, as an elected leader."

Harrell said wealthy companies would pay "a few cents more for every hundred dollars in revenue." (See the cost breakdown at the bottom of this story.)

Sponsored

Harrell went on to say he's "not trying to run businesses out of Seattle. Seattle is open for businesses." He said he'd continue to monitor the business environment Seattle offers.

But he also said part of offering a good business environment means that people are sheltered, schools are funded, and the city has a good plan for growth, referring to his One Seattle comprehensive plan.

Mayoral candidate Katie Wilson has been working to promote progressive tax policies like this for a long time. She praised the plan's debut, but she gave all the credit to Councilmember Rinck and accused Mayor Harrell of taking too long to come around to the idea.

"It’s disappointing that it takes the threat of being unseated for our mayor to do the right thing," she said in a statement. "We need a mayor who will responsibly manage the city budget and lead on progressive revenue every year they are in office, not just in an election year."

Sponsored

If she's right, could this or any other mayor reverse or scale back this tax? And could a wealthy tech company move employees out of Seattle, citing this tax as the reason, pressuring a mayor to do so?

Councilmember Rinck said no, at least not for the next four years.

"Similar to how, when the city passes property tax levies to fund services, when we put something before voters, be it a spend plan associated with a levy, it's pretty tied to those exact spending areas," she said. "It's very challenging, if not entirely illegal, to go against the will of the voters, especially if we say we want this funding to go to those specific services."

The tax plan does have a sunset clause — it ends in four years. At that time, the City Council can renew the plan, without going back to the voters. The council could then adjust spending priorities in the next generation of the bill.

Mayoral candidate Wilson says she's also looking at other progressive tax options, including building on the Jump Start payroll tax, which also places a higher tax burden on wealthy companies, and a capital gains tax.

Sponsored

In his press conference, Harrell said that no option, including increasing the Jump Start tax, is off the table. He said he's not ready to announce anything at this time, but his staff is looking at all options.

Thanh-Nga Nguyen is the owner of ChuMinh Tofu and Vegan Deli in the Chinatown International District. She spoke at the press conference announcing the tax reforms, where she said she was struggling with rising labor costs, rising food costs, and rising rent.

Nguyen told KUOW she wasn't sure the proposed tax breaks would be enough to counter all those problems.

"To say enough - we don't know," she said. "But at least it will leave us some room to breathe."

More details on the B&O tax plan.

Here are the nuts and bolts of how the tax would work, if approved by the City Council, and then ratified by voters in the fall election.

- Companies earning less than $2 million in gross receipts receive a 100% reimbursement for their B&O taxes. Gross receipts means any income that comes in, before any bills are paid or paychecks signed.

- For companies earning more than that, the first $2 million is still B&O tax free. The income over that amount is taxed at the following new rates:

- Retail, wholesale and manufacturing companies would pay $0.34 for every $100 in receipts (the old rate was $0.22).

- Service companies such as law firms would pay $0.65 for every $100 in receipts (the old rate was $0.43).

- 90% of companies would see their taxes go down, the city estimates.

- 76% of companies would see their B&O taxes completely reimbursed.

- Seattle's B&O taxes are separate — and much smaller — than Washington State B&O taxes.

The plan now goes to the city council for consideration. If passed, the measure would go before voters in the November election.