How to throw a low-carbon footprint holiday dinner party

It felt very Chez Panisse in my head, but the reality was more chaotic.

I was planning a low carbon (but high carb!) dinner party for my sister Alyssa and her fiancé, Riley.

In the past, I’ve dropped a chunk of cheese on a plate, hoping it would distract from the fact that I was still cooking the main course. This habit started in graduate school, when my husband and I spent a large portion of our small income on wine and cheese.

I wanted to take care of my friends, to bolster them with calories that would help them face the world. But my focus on abundance often led me to prepare foods with a large carbon footprint.

I wondered if I could keep that feeling and purpose — feeding people, providing comfort and community — but shift my focus to preparing more sustainable foods.

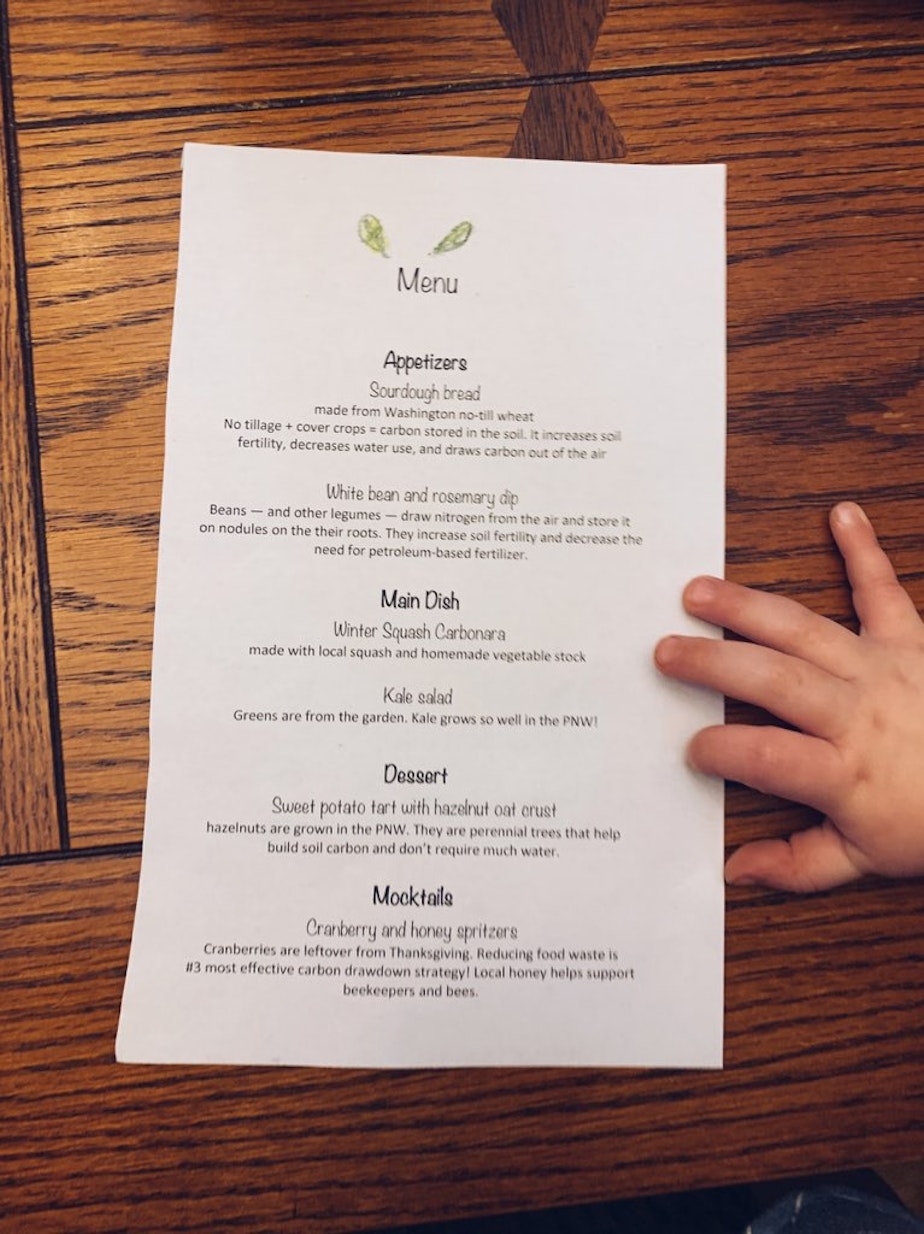

With that in mind, here’s what I made for dinner.

Sponsored

Appetizer: No-till wheat sourdough bread

I scrambled to cut up the vegetables for a squash pasta, trying to peel the acorn squash quickly without slicing a finger. I sautéed onion and garlic with one hand while stirring a cranberry honey simple syrup with the other.

My daughters tore through the kitchen, screeching as they chased each other around an endless living room-hallway-kitchen circuit.

The sourdough rose slowly on the counter, taking its sweet sourdough time. Sourdough moves languidly in the winter, taking a longer time to wake up.

Sponsored

For the bread, I used flour from Shepherd's Grain, a no-till wheat collective in eastern Washington. Most annual crops are grown using a plow to till — or turn over — the soil. Tilling makes the soil look neater and can release nutrients that help plants grow better in the short term.

In the long term, though, it depletes the soil. Dead soil washes away in rain or blows away on the wind, as it did during the Dust Bowl. The plow — long a symbol of American farmers’ hard work and mastery over the land — is actually killing the soil.

No-till wheat, on the other hand, stores carbon in the soil.

When roots come in contact with the soil, mycorrhizal fungi create a symbiotic relationship between plant and soil. Other microorganisms set up shop. The soil becomes dark brown and spongy and teeming with life. The mycorrhizal fungi forms pockets that catch and hold water, making the wheat harvest more resilient to drought.

The relationship between the roots and soil and microorganisms captures carbon and stores it in the soil.

Sponsored

(Project Drawdown ranks conservation agriculture — which includes no-till farming — as the #16 most effective method for drawing down carbon from the atmosphere.)

Shepherd's Grain produces excellent flour — it's used in Northwest bakeries, including SeaWolf, Bakery Nouveau, Grand Central Bakery, and Macrina's baguettes — and is very affordable. Town and Country Markets has it on sale right now for $2.50 for a 5-pound bag, which means that each loaf I bake costs less than a dollar. (And yes, I'm stocking up.)

As I shaped the bread, my sister arrived early and let herself in the front door. She helped my daughter set the table. She read books to both girls while I blitzed white bean dip in the food processor.

Beans are good for the soil, too. Legumes can fix nitrogen from the air and store it in root nodules, where it can help feed other plants without the use of fossil fuel-based fertilizers. When the beans die, if the roots are left in the soil, they will release nitrogen and help support future plants. This is why beans are often used as both a food crop and a cover crop — that is, a crop that enriches and protects the soil between growing seasons.

Almost an hour later, we finally sat down to dinner. Riley cut through the still-too-hot bread, dodging the steam. The bread was soft, our slices pillowy and huge. The bean dip had hints of rosemary and a sharp garlic tang.

The air smelled like flour and sour yeast. It smelled like home.

Main course: Mostly plants

The main dish was squash carbonara, the cream of a traditional alfredo sauce replaced with a squash puree. We spooned a hazelnut crumble on top, nutritional yeast standing in for the tang of Parmesan, the crunch of the hazelnuts a counterpart to the creamy pasta.

Sponsored

There is value in talking about where food is produced and how to support local farmers.

But when it comes to reducing your carbon footprint, there’s one very simple rule: Eat a plant-based diet.

Professor Charles Barnhart, an environmental scientist at Western Washington University, and a close friend, said when you’re calculating carbon costs, what you eat is more important than how far it has traveled.

“You can eat Chilean avocados and French wine every day of the week,” he said. “And if you eat red meat one day, you’ll blow that carbon footprint out of the water.”

According to a recent study, the climate impact of beef is approximately 100 times as much as the same amount of plant-based calories.

“But if you imported French cheese instead of French wine, that would no longer be the case,” Barnhart said.

Cows are a problem because they require clearing vast areas of land — which often requires cutting down trees and destroying local ecosystems. Cow burps produce methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

("People like to say cow farts because it's funny," Barnhart said, "but 95% of methane emissions come from cow burps.")

Even though methane doesn’t linger in the atmosphere as long as carbon dioxide, it absorbs heat more effectively. In the first two decades after it’s released, methane is about 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Meade Krosby, a senior scientist in the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington, said there are simple rules for lowering your carbon footprint: “Buy local, buy seasonal, buy low on the food chain.”

“But I want to turn this question on its head,” she said. “So much of the framing in the media is about personal lifestyle.”

Our individual choices matter, Krosby said, but “we can’t meet our carbon goals through individual action alone.” Instead, we also need to act collectively to demand a rapid shift away from fossil fuels.

“The most important thing you can do at a dinner party is to talk about climate change,” she said. When you do talk to others about climate change, she said, “Lead with your heart.”

As a climate adaptation scientist, she’s learned to share her emotions alongside the science. “We are people too,” she said. “We have families. We don’t want people to suffer.”

In those conversations, she said, make sure to center climate justice. It’s important to focus on frontline communities, those who will be most impacted by the climate crisis. These communities include indigenous people, people of color, and people with lower incomes. They are the people who are least responsible for rising greenhouse gas pollution, but they are hit first and hardest by the impacts.

She also said it’s important to give people things they can do and ways to get involved. Action is an antidote to despair.

At your dinner party, give people postcards to write to elected officials, urging action. Talk about where their energy is coming from and whether they need to be advocating for a cleaner energy mix. Talk about how you can support the frontline communities that are out there doing the work.

“People need to know that it’s not too late," she said. "There is still so much we can do."

Dessert: Hazelnuts and sweet potatoes

For dessert, I made a sweet potato tart with a hazelnut crust from Andrea Bemis's Dishing Up the Dirt. (Bemis and her husband have a farm just outside of Portland, Oregon.)

Hazelnuts are perennials, which means their bushy trees grow back every year. Perennial foods are important because they allow the soil to remain undisturbed. Hazelnuts grow in the Pacific Northwest, so they require less irrigated water than almond trees, which are typically grown in regions prone to drought.

My tart was supposed to bake at the same temperature as the bread. I slid it in the oven for those last 15 minutes of bread baking and felt superbly well-organized.

And how did the tart taste?

Reader, I burned it. Forgot to set a timer, and completely incinerated it.

Riley and Alyssa helped me scoop the filling and top layer of crust out with a spoon. We ate very small helpings of tart out of ramekins and talked about how delicious the roasted hazelnut and caramelized sweet potato would be if slightly less burnt.

Making this dinner reminded me that part of sustainability is slowing down, making less plans, paring down the menu. Making time for conversation and lingering over food.

A few days later, I had my friend Kaitlin over for another low-carbon footprint dinner. I made bread and carrot soup and chocolate hazelnut tapioca pudding. It was simple and tasty, and I rushed around a little less.

I did promise her kale salad, but it got dark quickly, and I couldn’t harvest the kale from my garden. Luckily — as two, sleep-deprived mothers, and three hungry children — we were happy to just eat soft, warm foods.

As Alison Roman says in her cookbook Nothing Fancy, the word “entertaining” makes it sound like having people over is a performance.

This is not a performance. This is our life. We can refuse to rush. We can say that our community is more important than capitalism, that we want to eat well without causing harm to others.

An important part of throwing a low carbon dinner party is talking about how to say no to that system, how to imagine a different way forward.

After talking to Barnhart and Krosby, I have a new formula for dinner parties.

Most important? Talk about climate change. Allow myself to show emotion, even when that emotion is fear or anger. Even if that emotion makes me break down, sometimes.

Next, make a large and satisfying plant-based meal. Donate the money I saved from not buying expensive meat or cheese to a local organization fighting for large-scale change. Focus my donations on people in frontline communities. Support indigenous communities.

Give people one practical thing they can do — contact a representative about a specific bill, demand that their energy company transition away from coal and natural gas, or write a letter to the editor about their vision of a more sustainable future.

Christina Scheuer is a writer and editor who lives in Seattle and uses the Instagram hashtag #100daysofclimateaction. She was previously an English professor at North Seattle College.

The Seattle Story Project: First-person reflections published at KUOW.org. To submit a story or note one you've seen that deserves more notice, contact Isolde Raftery at iraftery@kuow.org or 206.616.2035.