Japanese Americans remember the legacy of 'camp' 80 years after their incarceration

When Kim Ima was a kid, she often heard her family refer to “camp.”

“That was Henry." "From camp?”

Or they would speak of something that happened “before camp” or “after camp.”

But for a long time, Ima didn’t really know what that meant. No one explained to her exactly what "camp" was or why it had happened.

By junior high school, Ima knew more about the history, and decided to write a paper about it. She thought since her dad Kenji was only a child when he was there, he wouldn’t remember much. But she found that “all he needed was for me to say something, and then he had so much to say.”

Kenji's experience with "camp" was the result of Executive Order 9066. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the order on February 17, 1942, 80 years ago this month. It was 10 weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

The order gave the military the right to exclude people from designated “military areas” in the US in order to prevent espionage and sabotage. As a result, about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry were torn from their homes on the West Coast and incarcerated in camps.

RELATED: The Significance Of The Word 'Exclusion' On WWII Memorial

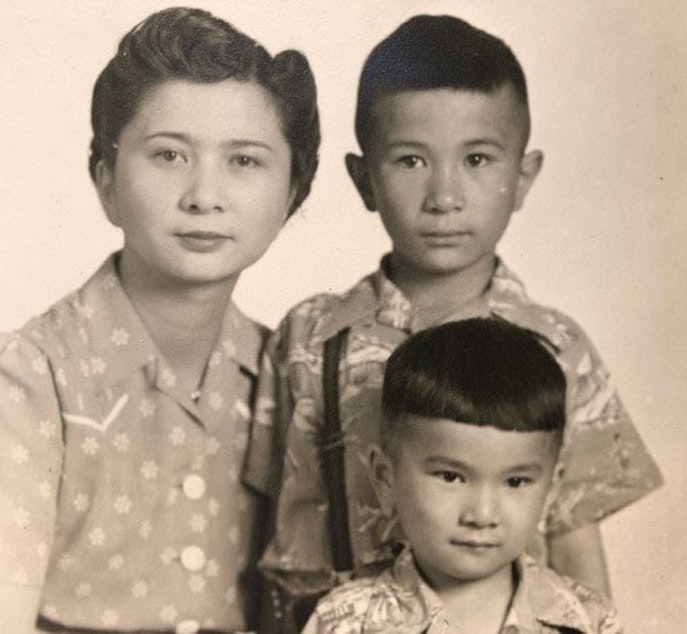

Kenji was born and raised in Seattle. He was only 4 years old when he, along with his parents and older brother, was taken away. The family first went to a temporary facility in Puyallup called “Camp Harmony,” and then to Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho, where nearly 9,200 people were incarcerated.

Sponsored

Kim says that what her father remembers most about the day they left home was being on his mother’s lap and feeling her anxiety, but not knowing or understanding what was going on.

Camp through Kenji’s child-eyes was a mixture of good times, like when kids outside the camp fence would bring him a popsicle if he gave them the change to buy one. And bad times, like getting scolded by his parents when he misbehaved. He remembers having many other children to play with, and the bustle of the mess hall where he ate three meals a day. He also remembers Christmas being celebrated with a live Santa Claus, and ice crunching under his feet in the winter.

Kenji was 7 years old when the family finally returned to Seattle. He couldn’t remember his life before camp. He had only known barracks, barbed wire, and soldiers with machine guns. He used to ask his older brother, “What is America like?”

His family was lucky enough to go back to running the hotel they owned before the war. But Kenji and his brother remember seeing signs on shops saying “No Japs,” and other racial slurs. He told his daughter Kim that “Seattle was not a totally welcoming place.”

Sponsored

Kenji is now 84, and in his old age, his daughter Kim said he is spending more time unpacking what happened at camp.

“The older he gets, the more he wants to talk about it,” Kim said. “He keeps coming round to the stories and having a deeper understanding of his own life."

Kim believes the trauma from the time has stayed with him.

“News hits him hard,” Kim explained. “It always feels like it’s slightly colored by his own life.”

Sponsored

But she said there are positives as well. Kenji grew up wanting people to be connected and to understand each other. Kim thinks this is what led him to become a sociologist. He works with recent immigrants, and tries to make things more fair for everyone. His experience at camp "continues to be what makes him courageous and what makes him speak out," she said.

RELATED: Memories Of Exclusion Inspire Seattle Architect's Work

Kim has continued to have conversations with her father and with other people who remember that time. She wrote a play called The Interlude which was performed at La MaMa in New York 2004. For Kim’s family, the legacy of camp is like a family heirloom, “like a touchstone in my pocket,” and she feels a responsibility to share the story.

Click the link above to listen to Kim and Kenji’s story and to the voices of Eugene Tatsuru Kimura, Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Shimako “Sally” Kitano, Shosuke Sasaki, and Victor Takemoto. Their oral histories are included in the Densho Digital Repository.