Love letter from Altadena: KUOW host revisits hometown in wake of LA fires

I've never felt so nervous while flying back to my hometown in Southern California. I also feel a sense of urgency among other passengers as we come in for a landing at Burbank International Airport.

Everyone's peering through what sliver of airplane-window they can find before we touch down. We all look like meerkats.

We want to get our first glimpse of the damage left behind by the Palisades and Eaton fires. Seeing it firsthand makes it real, makes it personal, especially for passengers like me.

Listen below to Part 1 and Part 2 of Angela King's journey to her hometown after devastating wildfires scorched the Los Angeles region, destroying homes and communities.

Part 1 Love letter from Altadena

Part 1. KUOW's Angela King returns to the neighborhood she grew up in after wildfires destroyed homes and communities surrounding Los Angeles.

Part 2 Return to Altadena

Part 2. KUOW's Angela King returns to the neighborhood she grew up in after wildfires destroyed homes and communities surrounding Los Angeles.

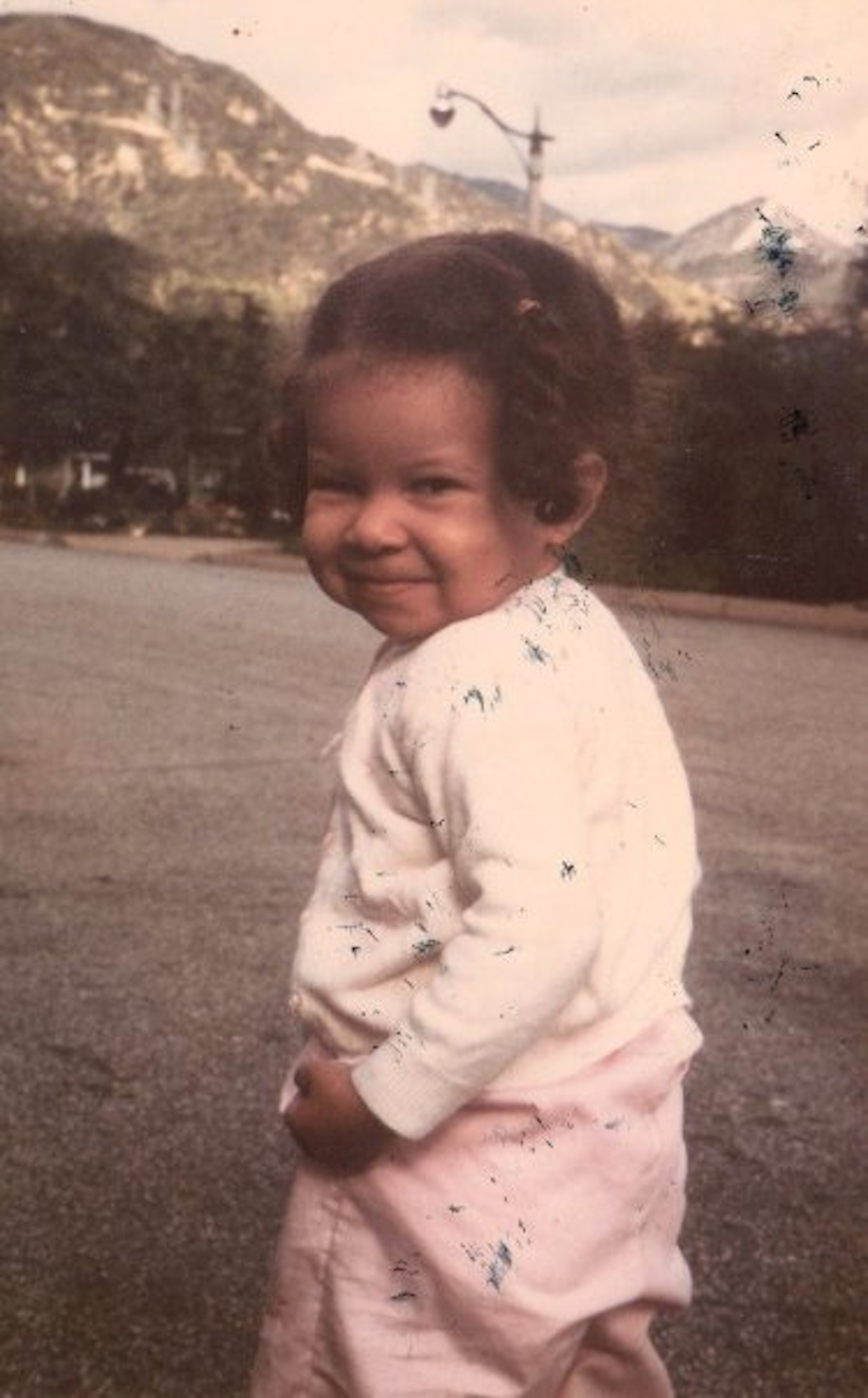

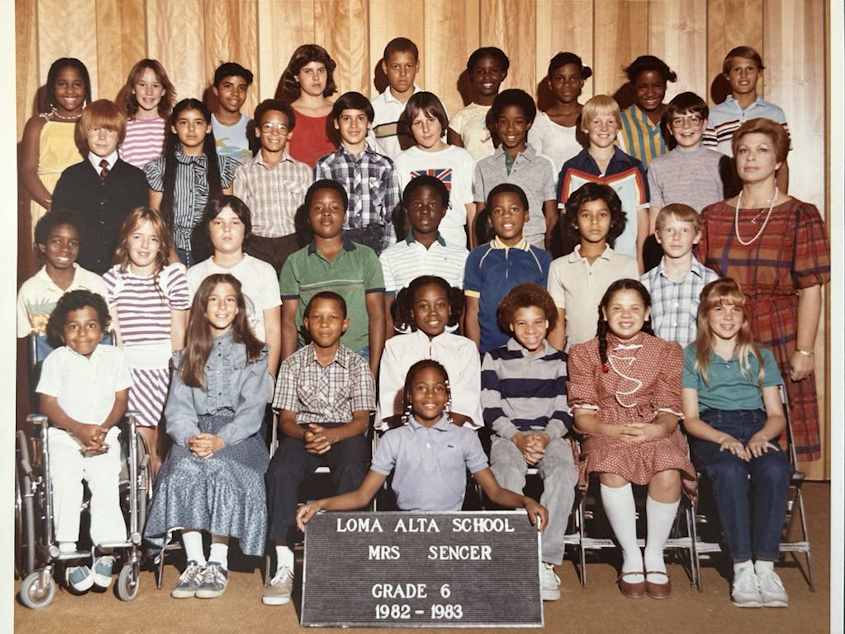

I grew up in the neighboring cities of Pasadena and Altadena. My grandparents' house, my aunt’s home, my childhood friends, and all but one of my grade schools are in Altadena.

I, along with the rest of the world, watched in horror as the Eaton Fire leveled a large swath of Altadena’s residential area on Jan. 7, 2025. Of approximately 9,400 structures destroyed, more than 6,000 were homes.

Images that emerged within hours of the fire’s ignition immediately conjured memories of the Lahaina, Maui fires in 2023. We all watched the same thing happen to Paradise, California, in 2018. Washington state lived through the devastation as well, when the 2020 Babb Road Fire decimated 80% of the town of Malden.

Sponsored

RELATED: How do the Los Angeles fires compare to the Great Seattle Fire? We mapped it out

This time, though, it was my turn to watch my hometown disappear in one night, knowing little could be done to defend it from flames that were being fanned by the infamous Santa Ana winds. These were 70 to 100 mph though. Locals call them “devil winds.”

I watched the desperate pleas on social media of people asking if anyone knew whether their house was still standing. One in particular stopped me in my tracks.

“If you’ve moved out-of-state, come home,” it said. “Help.”

So I did.

Sponsored

Altadena – The Community

Altadena was founded in 1887 in the shadow of the San Gabriel Mountains, directly north of the more famous city of Pasadena. Altadena flourished during the Great Migration of the early 1900s and became a beacon of a new ethnically diverse, middle class emerging after World War II.

Famous actors and social activists such as Sidney Poitier, Ossie Davis, and Ruby Dee lived in Altadena. Abolitionist Owen Brown, pioneering science fiction writer Octavia Butler, and seismologist Charles Richter also called Altadena home (along with the Smothers Brothers).

Altadena is also home to regular blue-collar workers like Jose Medina, who’s lived in his home for 40 years.

“This is the worst fire I’ve seen in California ever. The palm trees catch fire and catch the home on fire then another one,” Medina said. “I went up to the roof and [started] putting water [on the roof]. Then I help my neighbor putting water. I even burned my shoes. I know I need shoes but first I'm trying to help the people who most need it.”

Sponsored

Good to have you here

Miles and miles of fire damage make it nearly impossible to remember what Altadena looked like before the Eaton Fire. The street signs are gone. The palm trees look like spent matches. Block after block has been obliterated.

I meet Sarah Cole and her 10-year-old son sifting through the ashes of the family home they’ve lived in for eight years. When I tell Sarah I grew up here, she immediately hugs me and sobs quietly on my shoulder.

Sponsored

“Good to have you here,” she said.

It is a quick cathartic moment that reminds me that no Altadenan – former or current – is a stranger right now.

“This is our first time here. Just trying to stay strong for Eli,” Cole said. “He really wanted to come. I wasn't really ready, but today was the day.”

“We had one of those blocks everyone talks about. We just [organized] Christmas caroling a month ago and had hot cocoa. We had potlucks on the street.”

I ask Sarah if she and her family plan to rebuild.

Sponsored

“Too soon to know,” she said.

Generational wealth

According to 2023 Census data, the owner-occupied housing unit rate in Altadena is 78%, compared to the national average of approximately 66%. Many of these homes have been handed down from generation to generation since the late 1800s and early 1900s, especially among Black families.

“I hate to see our people lose what they've been able to do,” said Ridgley Curry. His home of 30 years was destroyed by the fire.

Many Black Americans looking to escape the racial discrimination of the South moved west during the Great Migration of the early 1900s. They later found a rare opportunity to buy property, predominantly on the west side of Altadena, amid the discriminatory “redlining” practices of the time. This allowed them to acquire and start building generational wealth.

As of 2023, 81 percent of Altadena’s black residents owned their homes, nearly twice the national average. Almost half (48%) of Black households/units were either destroyed or seriously damaged by the Eaton Fire.

RELATED: Here's how climate change fueled the Los Angeles fires

Now a new grassroots movement has taken root in the ashes. The “Altadena is not for sale!” campaign urges fire victims not to sell their property to, what neighbors have now dubbed, “the vultures.” The fear is developers will buy the land from those who can’t afford to rebuild and erase the historic charm and ethnic makeup of Altadena.

“I'm rebuilding. This is home to me,” Curry said. “I'm going to make it a beacon of what can be built.”

Altadena's diversity

Census data from 2023 showed 41% of Altadena is white, 27% Latino, 18% black.

“As a kid, it was my normal to live in a society that was integrated both socioeconomically and ethnically-racially,” said Norah Switzer Small, a high school classmate of mine. “I didn't know how unique it was until I went out into the world.”

Norah, like many Altadenans, now lives in the home her parents purchased in the 1950s. It survived the 1993 Kinneloa Fire and now the Eaton Fire, thanks in part to fire mitigations made to her home.

“We’ve stuccoed under our eaves,” Small said. “The attic and crawl space vents have ember screens. We have a hard defensible space around our home.”

Norah’s husband Jeremiah also played a crucial role in saving the family home. He’s a member of the Altadena Mountain Rescue Team. He also owns a pump he and four other neighbors used to suck water from their swimming pools and onto the flames.

“When I first saw the heavy flame crest the ridge, I thought this is too much. I really second guessed whether I should stay,” Small said. “Somebody I never met before then parked in the middle of the street and said, ‘How can I help?’ I said, ‘Start putting out fires.’ Then we realized we couldn’t fight the wind. It was almost blackout conditions. We couldn’t see because of the ash in our eyes and we realized that that was our ‘go point’ and leave it to fate at that time.”

Fate was kind. Norah and Jeremiah’s house is still standing.

“We’re determined to be an anchor for our community,” Norah said. “We’re probably going to take in a neighbor or two because the people are what make Altadena special. I would love for those people to stay, so whatever we can do to support them, that’s what we want to do. I don’t know what else to do.”

Historic architecture

In addition to being one of the most racially integrated areas in all of California, Altadena is known for its rich architectural history. The nonprofit Altadena Heritage was founded in the 1980s to advocate for the preservation of historic homes, mansions, and buildings that were being leveled to make way for newer housing.

RELATED: FireAid concerts raise estimated $100 million for LA wildfire relief

Social activist and visionary architect Gregory Ain designed the home Nor Oropez lived in with his wife Carlyn and 12-year-old daughter Mila. Their home was one of 21 that burned down on their block.

“Carlyn and I would love to rebuild and make it as close to the original as possible because it is a special home,” Nor Oropez said. “Every time I've gone away on vacation and come home and open the door, it feels really comfortable. I never thought I'd live in a home like that.”

Oropez never thought he’d have to move back in with his parents, as a man in his 50s.

“It’s such a surreal thing to start from zero, and insurance only gives you so much for the rebuild,” he said. “With all of the homes destroyed, there will be competition for homes, labor. Money talks and I don’t have those kinds of resources."

What's next?

Before anyone can rebuild in Altadena, Los Angeles County officials say an estimated 4.5 million tons of hazardous waste and debris must be removed.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers also reports more than 1,000 people are working to clean up the toxic aftermath.

Several haunting questions remain though:

What will happen once the first heavy rain arrives?

What about the potential for mudslides, and groundwater contamination?

What about all of the secondary health effects that will rear their heads years from now?

What will this community still need 5 to 10 years from now?

Will help still be here?

You can find a list of charities helping LA fire victims here. LA city officials say the groups and their charitable efforts have been vetted.

You can donate specifically to Eaton Fire victims here.