Whale watchers need to stay farther away from endangered orcas, legislators propose

For an orca hunting chinook salmon in the murky depths of the Salish Sea, hearing is more important than seeing.

That makes boat noise a big problem for whales that are struggling to find enough to eat.

The Washington state House of Representatives on Tuesday looked into restricting whale watching boats to help save the region's endangered orcas from disturbance — and extinction.

"Reducing vessel presence is critical right now while we work to increase chinook numbers," said Amy Windrope with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, testifying before the Rural Development, Agriculture, & Natural Resources Committee. "Fewer vessels means the whales are more capable of finding food more quickly.”

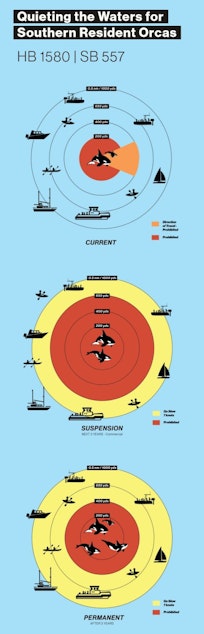

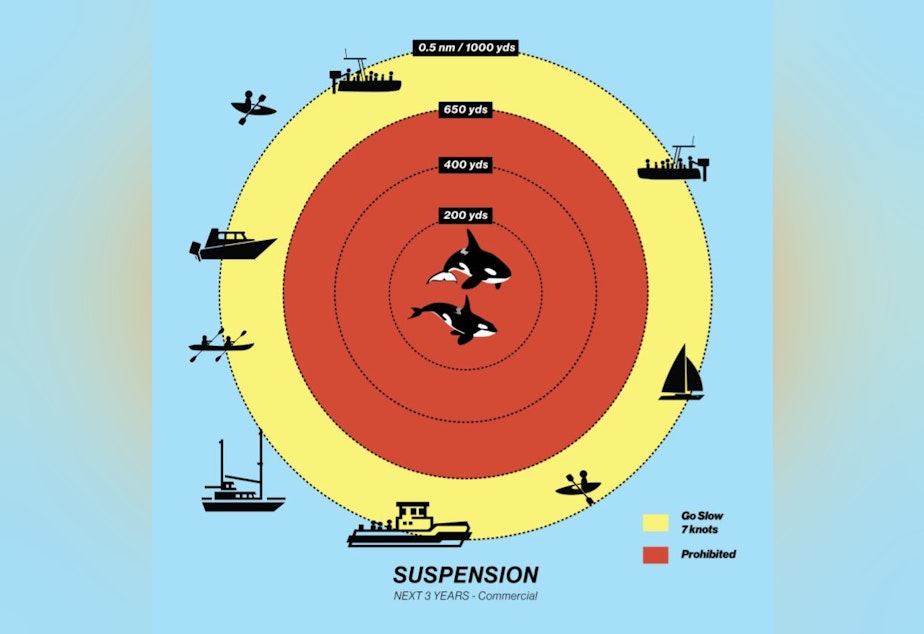

Windrope testified on a bill proposed by her boss, Gov. Jay Inslee. For the next three years, it would keep whale watching boats 650 yards away from the endangered orcas.

That distance, more than triple current rules, amounts to a de facto ban on watching those whales from a commercial boat. Other boats would have to stay 400 yards away, and whale watch boats could continue to get closer to non-endangered whales.

“Six and a half football fields is quite a long distance,” said Erin Gless, a naturalist with Island Adventures, an Anacortes-based whale watch company.

Sponsored

“The global standard for viewing orcas outside the state of Washington is actually 100 yards,” Gless said. “So Washington state is already double what is kind of universally accepted.”

Fact check: Canada requires all boats to stay 200 meters (219 yards) from any orcas (endangered or not) and 100 meters from most other whales.

Gless and other whale-watch industry officials who spoke at the hearing agreed that boat noise is bad for orcas.

San Juan Safaris owner Brian Goodremont said existing regulations and the Pacific Whale Watch Association’s voluntary practices had already resulted in “near-silent conditions around southern resident killer whales.”

Industry supporters said speed, not distance, is the key factor in underwater noise. They said they supported the bill’s call for an 8 mile per hour speed limit for all boats within a half mile of any southern resident killer whales.

Sponsored

“It will quiet the water substantially around the whales,” Gless said.

The bill would also create a licensing system to limit the number of orca-watch tours once its three-year moratorium lifts.

About 500,000 people take a whale watch tour each year in Washington and British Columbia.

San Juan Island resident Janet Thomas with the Orca Relief Citizens Alliance said she hasn’t gone on a whale watching tour in nearly 20 years.

“Most of us don't go anymore because it's too painful to see what the whales have to deal with in their core habitat," Thomas said.

Sponsored

A 2015 study by the Whale Museum in Friday Harbor found an average of 19 boats within a half mile of orcas from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. during the peak summer tourism season.

“They're basically being watched constantly,” said Mindy Roberts of the Washington Environmental Council.

Studies show that recreational boaters, often ignorant of the rules, violate the orcas' safety perimeter much more often than whale watch boats do.

Whale watch supporters said their boats model good behavior for others on the water, helping to deter boaters from getting too close to the orcas.

State officials and environmentalists said the whale watch boats often act as magnets, drawing crowds of boats that can interrupt the endangered orcas’ efforts to listen for their next meal of salmon.

Sponsored

"This year is particularly important because we know there are several undernourished and pregnant orcas, whose loss could have lasting impacts," Windrope said.

The bill would not limit how other types of whales are watched.

“We have ample opportunities for whale watching, including minkes, gray whales, humpback whales and the transient orcas that are currently expanding,” Roberts said.