Our local seaweed is disappearing. Could farming help conserve it?

In 2016, Washington's first commercial seaweed farm broke onto the scene. It was the result of unprecedented collaboration between local tribes, state agencies, marine researchers, and local conservationists. As climate change begins to threaten Puget Sound today, a robust seaweed industry in the region could help combat its most negative effects.

Seaweed has a storied history in Puget Sound. The cold water supports lush kelp forests, which are a cornerstone of the underwater ecosystems.

Historically, seaweed has been cultivated by a host of tribes in the region for food and a bevy of practical uses. But despite our ideal conditions, Washington only has a single commercial seaweed farm. That's because the state is still figuring out how it can walk the line between growing seaweed for industrial reasons, and growing it for environmental ones.

Washington's next cash crop?

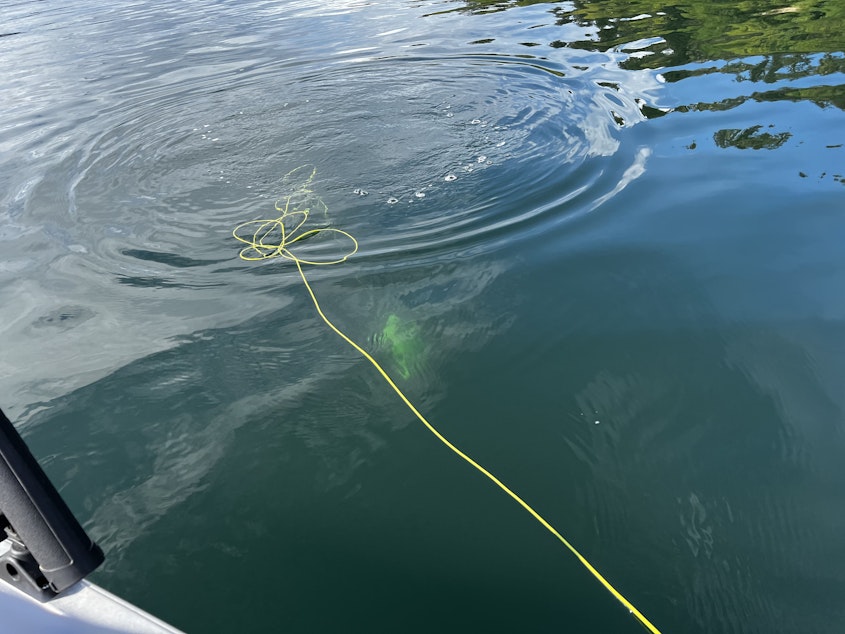

"The ocean has a tendency to beat up and destroy most everything you put in the water," said Mike Spranger, who's on track to be Washington's second ever seaweed farmer, and the first in King County.

Spranger is riding a wave of interest in seaweed farming in Puget Sound. A retired tech worker, he came across a podcast heralding the fast-growing algae as the next cash crop in the United States -- and one perfectly suited for our cold Salish Sea waters. That was just over a year ago, and without any prior aquaculture expertise, Spranger decided to go all in on 10 acres at the south end of Vashon Island.

Sponsored

"The stuff just grows like crazy," Spranger said. "In about four months you can have a seaweed blade that's 12 feet long, chock full of protein."

Seaweed is a kind of miracle plant. It has multifaceted uses in food, from wrapping your sushi to crunchy snacks you can find next to your favorite potato chips. There's also a growing interest in kelp as a biodegradable, reusable plastic, and it's shown great promise as a fertilizer.

But one of the best cases for growing seaweed is something that can't be manufactured, or sold.

"Think salmon, think orcas, think rockfish," said Betsy Peabody, the executive director of the Puget Sound Restoration Fund (PSRF). "All of these different species are dependent on healthy kelp forests."

Seaweed — and its many varieties, from eelgrass to bull and sugar kelp — is a cornerstone of our local ecosystems. On the Olympic Coast, otters take refuge in the cooling kelp forests. In Puget Sound, the small spores it sheds are food for our local shellfish, like Olympia oysters and pinto abalone, two species in need of conservation due to overharvesting and the rising acidity of Puget Sound. Seaweed can help with that problem too — just like our terrestrial forests on land, seaweed forests gobble up carbon dioxide, a leading cause of ocean acidification.

Sponsored

With a growing market and lauded environmental benefits, there's a growing interest around the country for new farms in the Northwest. But the industry is far from robust here, and there isn't a clear roadmap for starting new farms.

"A lot of people come to me and they're like, 'I don't even care if I make money,'" said Meg Chadsey, and ocean acidification specialist with Washington Sea Grant. "They're like, 'I just want to give something back.' How can you fault anyone for that?"

At the moment, Washington has a tedious permitting process. Water is a valuable resource, and in Spranger's case, he needed approval from the Washington Department of Ecology, the Army Corps of Engineers, the Coast Guard, and from the Puyallup Tribe, which has usual and accustomed rights to their traditional uses of the waters around Vashon Island. The permitting process alone can take more than a year and cost tens of thousands of dollars.

Spranger has approval from all of those stakeholders, and is waiting on a final permit from King County.

"There's a lot of steps. A lot of the agencies have never done this before," he said. "They've definitely done other aquaculture, like shellfish. But adding the seaweed component was a new thing for them. So they were learning as they were going along."

Sponsored

Balancing conservation with industry

The hesitation to open the waters for rapid seaweed farming is a good thing, according to Meg Chadsey.

"You can look at other places in the world, where there isn't such a robust permitting process, and see what happens to those areas when private business gets ahead of the public's ability to put the brakes on, to protect things that need to be protected," Chadsey said.

Sponsored

Conservation and industry walk a careful line, with one frequently helping support the other. There's optimism that the careful approach to seaweed farming so far means that the state can confidently strike that balance.

"We have the opportunity here, for the first time, to think about conservation and management and so forth of this resource in a much more noncontroversial way," said Thomas Mumford, who tried developing seaweed farms with the Department of Natural Resources back in the 1970s and 80s.

At that time, Mumford worked with the Lummi Nation to understand best practices and uses for seaweed. But when the state tested some early farms, they got complaints from people living on the water that it was spoiling the natural beauty of Puget Sound, and interest died down.

The resurgence in seaweed, propped up by its importance for battling climate change, is an optimistic change for Mumford.

"It's all about trust — we're going to do something that's going to work for you, work for us, and involves everybody," Mumford said. "And isn't something that's going to be crammed down your throat. That was not thought about in the mid-80s at all."

Sponsored

Betsy Peabody from the PSRF is optimistic that new farms can work with conservationists to help replenish disappearing seaweed forests.

"There are ways in which kelp farming can help bolster the seed supply, potentially, of kelp forests," she explained. "If a farm was producing a portion of bull kelp as part of its portfolio of kelp species and products, then maybe that bull kelp could grow and mature and release spores into the water that would be supportive of nearby kelp forests."

Even with all the current optimism around seaweed, there are big existential factors at play. There is a lot of evidence that local farms improve the health of our local ecosystems. But if the world doesn't act on climate change and oceans continue to warm, it may become impossible to grow seaweed at all.

"This is going to be hard for some people to hear," Chadsey said. "Seaweed farming on what I'll just call the 'artisanal scale' ... can't capture enough carbon to address ocean acidification or climate change on any kind of big scale."

For those pioneering the state's latest aquaculture industry, questions abound. Can seaweed farming live up to the hype and be a benefit to farmers and conservationists? Can it walk that fine line of helping the environment more than it hurts it? Is there enough of a market for seaweed products to inspire new farmers in the first place? And does any of it matter in the face of global climate change?

For Chadsey, it's at least worth trying.

"The analogy I always use is when you have a cold, you crawl into bed and you drink lots of liquids and you do things just to give your body some strength and rest, so it can fight off what's hurting it," she explained. "You don't have to fix the global climate problem, I think, to have to do some good."