Outcry over deadly police encounters fuels successful legislative push in Washington

Last year’s protests against police killings and calls for racial justice have resulted in a landmark legislative session in Washington state.

Before lawmakers adjourned Sunday, they passed more than a dozen bills aimed at transforming police culture and increasing accountability.

One new law requires that police officers attempt to de-escalate dangerous situations; it makes deadly force a last resort (HB 1310). Another law makes it easier to decertify officers for misconduct so they can’t simply switch jobs (SB 5051).

Sakara Remmu is the founder of the Washington Black Lives Matter Alliance, which sought these changes.

RELATED: Taxes to environment. Washington wraps up 'historic' session

“We are now resetting the standard of what are and are not acceptable police tactics in community,” she said. “That is historic. But it is not a magic wand.”

Remmu attributed the passage of so many bills simply to public outrage and engagement in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.

Sponsored

“And lawmakers feeling the impact of their constituency, that was priority one,” she said. “It’s not enough to just walk into a room with a lawmaker and say, ‘we’re BLM, we demand this, that and the other.’”

Sponsored

Time to train

Now comes the implementation. Monica Alexander is interim director of the state’s Criminal Justice Training Commission. Her takeaway from this legislative session is "that reform is real. That people want change. That’s my big-picture take.”

She will have to train police —including young recruits — in these new standards, including the new law that requires officers to intervene and report when a colleague uses excessive force (SB 5066).

Policing “is a young person’s game, in terms of the physical agility, day-night rotations, working late, long shifts, and that’s great,” Alexander said. “But we have to help them to finish developing that frontal lobe and the courage it takes to stand up against the scrutiny of saying, ‘Hey I don’t think that’s the right thing.’”

Alexander is also a retired Captain with Washington State Patrol. She said she’s had calls from former colleagues who fear these changes. She makes the case that the new laws reinforce what good cops already do.

Sponsored

“I said, ‘so let’s think about this, how many people you’ve stopped, how many people you’ve arrested, how many times you’ve had encounters with our public. And guess what, you have done a great job.’” She said. “If we say, 'listen, you’re doing 90% of this, we’re asking you to come another 10%.'”

Alexander argues that officers will be persuaded if they understand it is in the name of safety for everyone involved.

And members of law enforcement backed some of these bills. The Washington Fraternal Order of Police supported a tactics bill (HB 1054) that banned neck restraints and restricted vehicle pursuits. The group also supported creating a statewide database of every incident where a police officer uses force (SB 5259).

President Marco Monteblanco said his group, which has more than 3,000 members statewide, worked hard to build public trust.

“I think we’ve done a very good job of that this year, and hopefully people recognize that as we’re going forward, that there are organizations out there that will work with our communities to try to find common ground,” he said.

Sponsored

Decertification

But law enforcement groups — including Monteblanco's — opposed creation of the nation’s first statewide agency to allow civilians to investigate officers’ use of deadly force (HB 1267). Monteblanco said he hopes lawmakers will be open to changes in the legislation if problems arise.

“We know that independent investigations are important, we’ve supported independent investigations for deadly force situations. That remains true today,” he said. “Going forward if there needs to be tweaks to it, we’ll work with our community partners.”

The decertification bill also shifts the majority on the state’s Criminal Justice Training Commission, which oversees that process, from members of law enforcement to civilians.

Puyallup tribal member Tim Reynon took his seat on the commission as a tribal representative this spring.

Sponsored

“It was very empowering to be able to be at that table,” he said, and “ask questions that needed to be asked.”

Equally gratifying, Reynon said, is that he and another new civilian representative were “welcomed with open arms.”

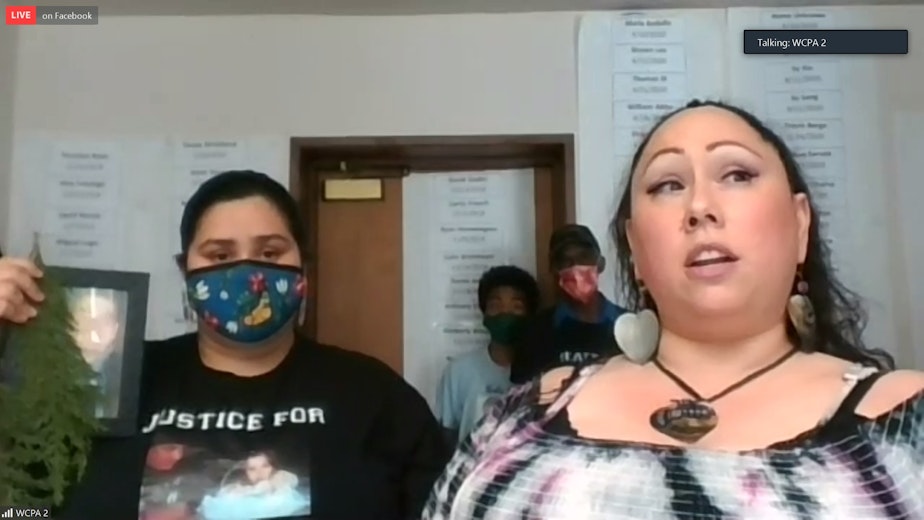

Reynon is a member of the Washington Coalition for Police Accountability. He said in new mandates for policing you can see the “lived experience” of people who campaigned for these laws. He said new restrictions on police firing at moving vehicles might have prevented the deaths of Puyallup tribal member Jackie Salyers, who was shot by Tacoma police in 2016, and Giovonn Joseph-McDade, who was shot in his car by Kent police in 2017.

“Had some of this legislation been in place, many of the people we’ve lost over the past years would still be here today,” Reynon said.

He said this year’s groundbreaking effort at the Washington legislature feels more significant to him than the rare guilty verdict against a police officer seen in Derek Chauvin’s trial last week.

Sponsored

“The thing that really gives me hope is the work that we’ve been doing during this legislative session, during the past five years, bringing communities together to combat police violence together,” he said.

If these new laws are working, Reynon said, his vision is for more situations involving police to be de-escalated and peacefully resolved.

“I have three young, Native American, brown boys that are between the ages of 12 and 23 right now,” he said. “I will be able to send my sons out the door not having to worry about whether they’re going to have a deadly interaction with law enforcement.”