Replacing West Seattle Bridge expected to take half a decade

If the badly cracked bridge can’t be fixed, transportation officials say it would take at least four to six years to replace.

There are no quick fixes in sight for the troubled West Seattle Bridge, which was closed to all traffic in March due to a growing network of cracks in its underside.

Workers dangling from climbing harnesses drilled into the bridge last weekend to take samples and see what shape the concrete is in. The samples are being sent to a lab where they will be sprayed with an acidic “salt fog” to learn how susceptible the concrete is to corrosion.

Engineers have also used ground-penetrating radar to peer inside the bridge for cavities and corrosion near its internal steel supports.

Seattle transportation officials say they won’t know until late June or early July whether the badly cracked bridge can be repaired at all.

A repaired bridge would have fewer lanes and might open in 2022, “at the earliest,” according to the Seattle Department of Transportation. It would have an expected lifespan of 10 years.

Sponsored

The West Seattle Bridge opened in 1984 and was supposed to have a lifespan of 75 years.

If the bridge cannot be fixed, the Seattle Department of Transportation says it would take at least four to six years to replace.

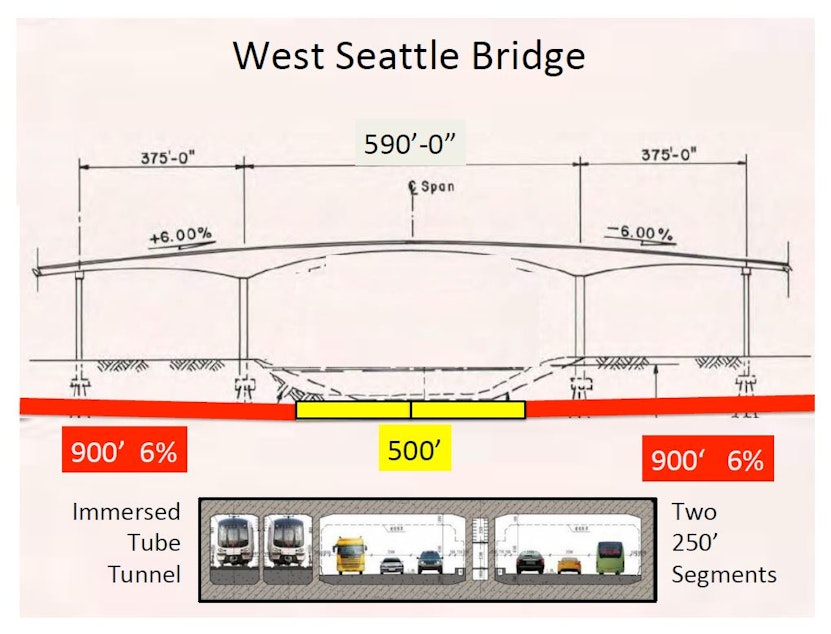

City officials say they are seriously considering all options, including a tunnel under the Duwamish River, proposed recently by retired civil engineer Bob Ortblad of Seattle.

Ortblad is proposing an “immersed tube” tunnel made up of giant concrete boxes fabricated in a shipyard, then dropped in a trench dug in the river bottom. It would have six lanes for cars and two for light rail.

Sponsored

“You can do the traffic and light rail in the same box,” Ortblad said. “It certainly wouldn't cost more than two new bridges.”

Sound Transit is planning a light rail bridge to West Seattle, with construction estimated to begin in 2022.

“A tunnel under the Duwamish was looked at, and it was determined to be impractical due to its depth and length,” Sound Transit spokesperson David Jackson said.

Sound Transit planners ruled out a tunnel in 2018, though they looked only at a bored tunnel – similar to the one dug with minimal surface disturbance but great expense and delay by the tunnel-boring machine dubbed Bertha beneath downtown Seattle for state Route 99 – not a trench tunnel.

Jackson said Sound Transit is not currently considering a tunnel or a bridge that could carry both traffic and trains.

Sponsored

Much of the sediment beneath the Duwamish River is contaminated with toxic waste, leading to the designation of the river’s last five miles as a Superfund site in 2001.

Ortblad said a 35-foot-deep tunnel trench would require digging 136,000 cubic yards of sediment, slightly more than the Port of Seattle dredges every year to maintain the shipping channel there.

The closest example of an immersed-tube tunnel runs beneath the Fraser River south of Vancouver, British Columbia. The province plans to replace the 4-lane George Massey Tunnel, built in 1959, with an immersed 8-lane tunnel or a bridge across the Fraser River.

The Delta Optimist in British Columbia reports that the new tunnel would require three years of planning and five years of construction.