Seattle CHOP killing: Lost evidence, official secrecy, a note home

Five years ago in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, a Black teenager was shot and killed in front of dozens of people. The killing and its aftermath — but not who was shooting — were caught on video, livestreamed to the world.

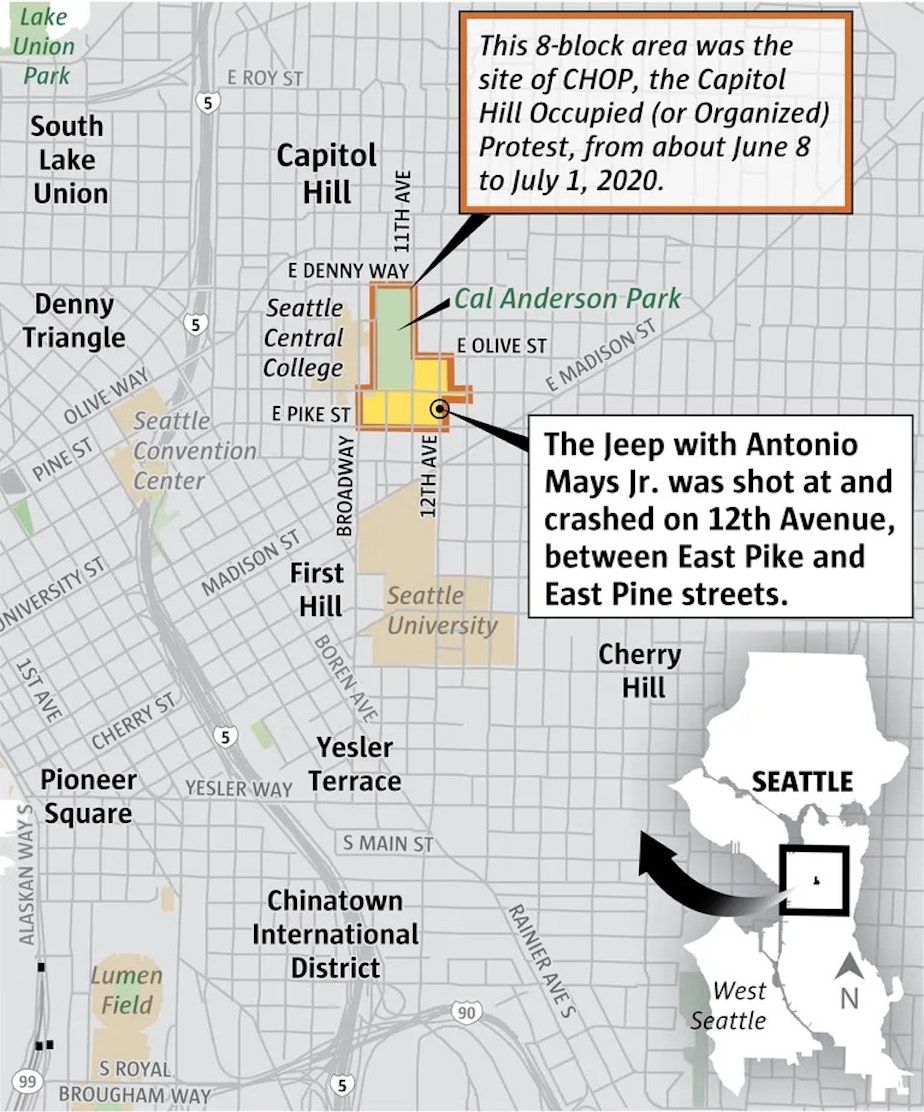

The homicide ended the Capitol Hill Organized Protest, a three-week encampment created after police abandoned the East Precinct, which drew national scrutiny and the ire of President Donald Trump.

But the killing of 16-year-old Antonio Mays Jr., who had traveled from his Southern California home to join Seattle’s racial justice protests, remains unsolved. And the case is shrouded in secrecy, as the city, in two related civil suits, has invoked a rarely used strategy to keep the investigation confidential.

New details have emerged that indicate potential evidence may have been lost in transit and that an FBI informant moved among the protesters. Seattle police Chief Shon Barnes said in a recent interview that, while there are no official suspects, detectives are still actively working the case and have persons of interest. Police are asking for the public’s help.

“We need people who were there inside of the area to come forward,” Barnes said.

RELATED: 5 years after CHOP in Seattle, teen’s shooting death is without answers

Sponsored

Here’s what we know about the case on the fifth anniversary of Mays’ death.

What happened to Antonio Mays Jr.?

Mays was shot and killed in CHOP, right outside the Police Department’s East Precinct, in the early morning hours of June 29, 2020. His death spurred city leaders into action. Two days later, police cleared the nationally scrutinized protest zone, ending CHOP after three weeks.

Mays was fatally shot and 14-year-old Robert West was critically injured in a stolen Jeep they were driving in and around CHOP. Some protesters believed someone inside the Jeep was shooting at them, but police have not said whether that occurred. Witnesses said in a livestream and told The Seattle Times that armed protesters guarding the barricades of the encampment were responsible for shooting at the Jeep.

Sponsored

The passenger-side windows of the Jeep were rolled up when it crashed, shattered with bullet holes. Photos of the aftermath also show the driver’s side window shot out, with shards of glass clinging to the frame. Police have not said who was driving, though city attorneys alleged in response to a lawsuit filed by Mays’ father that Mays was driving.

No ambulances arrived at the scene. Instead, protesters and witnesses frantically tried to drive both boys toward medical care. Raz Simone, a local hip-hop artist who’d earlier drawn notoriety for a video that showed him handing out an assault rifle from the trunk of a Tesla at the protest, drove West to Harborview Medical Center.

“I threw him in the car when they was all panicking / I took the owner’s keys,” Simone rapped in a video titled “CHOP Killings Freestyle” released last year. “I drove him to the ER, the police was all out brandishing.”

Protesters in another stolen car took Mays and tried to chase down an ambulance near the encampment. But the ambulance drove away from them, and it took 24 minutes for protesters to finally meet with city medics in a parking lot. By that time, Mays had died.

Sponsored

When Simone arrived to the scene, West “looked far worse” than Antonio Jr. and had a gunshot wound to the head and a possible severed artery in his leg, Simone told The Seattle Times.

“I prioritized Robert because he seemed unlikely to survive without immediate care,” Simone said in a text message Friday evening. “The second car didn’t arrive at Harborview for another 15 to 20 minutes. I believe Antonio might have had a better chance if they arrived when I did.”

Simone also said that while he became part of the headlines about CHOP, “dozens of white men were walking around CHOP with far larger firearms for days on end.”

The violence and its aftermath unfolded as dozens of people slept in tents, watched and broadcast the scene live over social media.

Why did Mays come to Seattle?

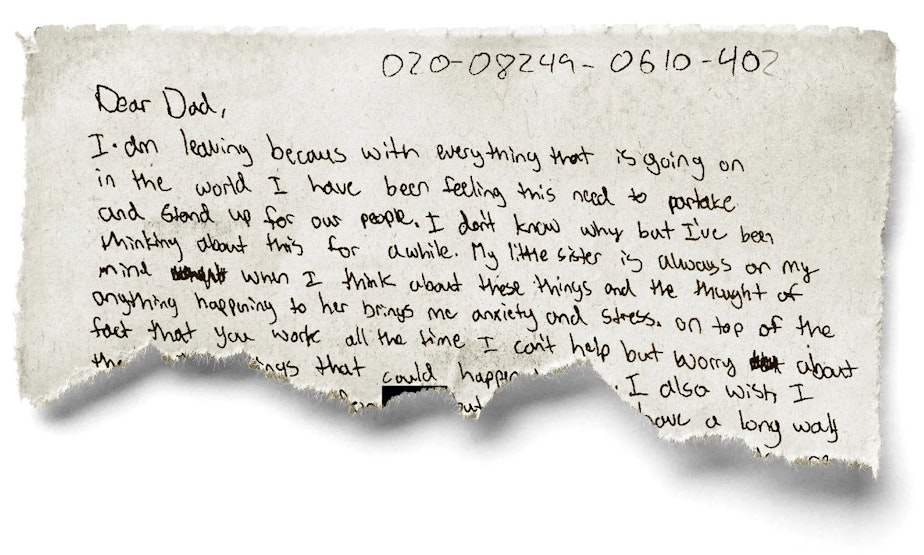

Less than a week before he died, Mays wrote his father a letter. He left it on an ice chest in their garage. Antonio Mays Sr. found it a few hours after his son had gone.

Mays’ handwriting is childlike but precise, filled with loops and curves and few hard edges. His letters slant slightly left.

“Dear Dad,” he begins, in a note obtained from the Los Angeles Police Department through a public records request by The Seattle Times. “I am leaving becaus with everything that is going on in the world I have been feeling this need to partake and stand up for our people.”

Four times he crosses out a word and begins again, as if unsure of what he’s trying to say. His little sister, he writes, is always on his mind. He’s on a journey, he tells his dad, to become a better person.

Sponsored

“I hope you can forgive me for leaving, but know that I am not running from home,” Mays writes. “I am fighting for a cause. One day I want my sister to live in a world where her skin won’t be the cause of any pain for her physically or emotionaly.”

“Don’t get angry or upset with my decision please,” Mays concluded. “I love you dearly your son.”

Mays Sr. immediately went to the police to report his son missing. He didn’t know where Antonio had gone until nearly a week later, when police told him he’d been killed in Seattle.

What does an “active” case mean?

Sponsored

Barnes said the case is still “open and active,” though he did not specify how many detectives were assigned to the case or how many hours are being dedicated to it. No homicide cases are closed as long as they are unsolved, he said.

This also means the public is blocked from learning what police have discovered in an investigation. Active criminal investigations are exempt from public disclosure in Washington state.

Mays’ father, still seeking answers in his son’s death, filed a formal complaint in 2023 against the Police Department with the office of police accountability over his frustrations with the lack of information on the case. But OPA rejected his allegations, finding five of them “inconclusive” and one “unfounded.”

This year Mays Sr.’s lawyer, who is helping him sue the city over his son’s death, asked Congress to investigate the killing.

“Despite the gravity of these incidents, there has been no accountability,” attorney Evan Oshan wrote in March in a letter to the U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. “No individuals have been arrested, and it appears that the investigations, if any were conducted were deeply flawed.”

What happened to the evidence?

On one of the video streams of the shooting’s aftermath, people can be heard instructing others to pick up shell casings that littered the ground. Police, unwilling to enter the CHOP zone, didn’t arrive until hours later. Barnes recently told The Times some people turned over physical evidence to the police after the scene had been scoured.

Police also appear to have lost possible evidence they obtained when, two days after the shooting, they cleared the protest encampment and arrested people who refused to leave.

In one arrest report, police describe finding a .22 bullet and fired shell casing in a protester’s cargo pants. That protester said she was holding onto these items from a shooting because she didn’t believe police would investigate properly.

While the report doesn’t specify which shooting the bullet and shell casing came from, the protester had been a witness to Mays’ death two days earlier.

The bullet and shell casing were then turned over to the prison transport driver and lost, according to the arrest report, “likely as a result of the volatility of the scene.”

Seattle police declined to reveal whether they had ever recovered the evidence and told reporters they would not comment on an open and active investigation.

Why doesn’t the public know more about the shooting?

While several protesters and witnesses have been willing to share their experiences of the shooting and CHOP, some reached by The Times have described fear of reliving trauma as the reason they do not want to share what they know.

Lawsuits by Mays Sr. and West could provide another path for the public to find out new information about the events of June 29, 2020. But Seattle officials have taken extra steps this year to guard any information the city knows about the shooting. Seattle city attorneys have asked for and won an “attorneys’ eyes only” confidentiality designation to use on any piece of discovery in the homicide case file.

These confidentiality designations are some of the highest protections a court can place on discovery. Under an AEO designation, an attorney cannot show the discovery to clients. That means Oshan, the attorney representing both Mays Sr. and West, can’t share details from the homicide file with them.

AEO confidentiality designations are uncommon and rarely used outside commercial litigation, retired King County Superior Court Judge William Downing said by email. At times, attorneys and attorney groups have protested excessive use of AEO designations, arguing they severely limit an attorney’s ability to litigate a case by restricting what can be communicated to a client. Oshan argued as much in court filings. He lost that argument in both cases.

Is there a pattern when it comes to unsolved homicides in Seattle?

A Times analysis shows Mays is one of 13 teens in Seattle whose homicides have gone unsolved by the Police Department since 2020, which the department confirmed.

Among them is 17-year-old Amarr Murphy-Paine, who died last year after being shot in the Garfield High School parking lot in front of other students.

RELATED: Family of Garfield High student fatally shot on campus sues Seattle Public Schools

Mays’ killing marked the end of CHOP, a protest area that captured the nation’s attention, from its hopeful early days to its descent into paranoia and violence.

What does the FBI know?

A 2020 intelligence briefing and Seattle Police Department emails obtained by The Times show that the FBI had an informant at CHOP as well as special agents. The informant meandered through the encampment, taking photos of right-wing agitators with guns and later described the scene to their FBI handler. The same informant expressed confidence that they could get recruited by CHOP security. The FBI then shared its information with Seattle police.

Glen Stellmacher, a protester turned independent journalist, was the first to publish some of these records in an article last month in Real Change, the Seattle nonprofit newspaper. Stellmacher has sued the city of Seattle for its alleged failure to release more public records he requested on exchanges between SPD and the FBI during the protests.

FBI intelligence briefings from 2020 obtained by The Times through public records requests describe two special agents, at least one of them undercover, who were assaulted at the racial justice protests. One left the scene with a broken nose.

The FBI declined to tell The Times if it is also investigating the Mays case, but the agency provided a statement it previously published in June 2020.

The FBI “routinely assesses the full spectrum of potential threats that come to our attention and works with law enforcement partners to address them, if needed,” the statement read. “While it would not be appropriate to address specific details of what you’re asking, every FBI office around the country has stood up a 24-hour Command Post and nationwide, Joint Terrorism Task Forces have been directed to assist our partners with apprehending and charging violent agitators who are hijacking peaceful protests.”

This story was published in collaboration with The Seattle Times. All three reporters of this story reported from CHOP in 2020.

Seattle Times reporter Sara Jean Green contributed to this story.