Seattle's rising rents are forcing out baby boomers

The housing market is hot, and older Seattleites are feeling the squeeze.

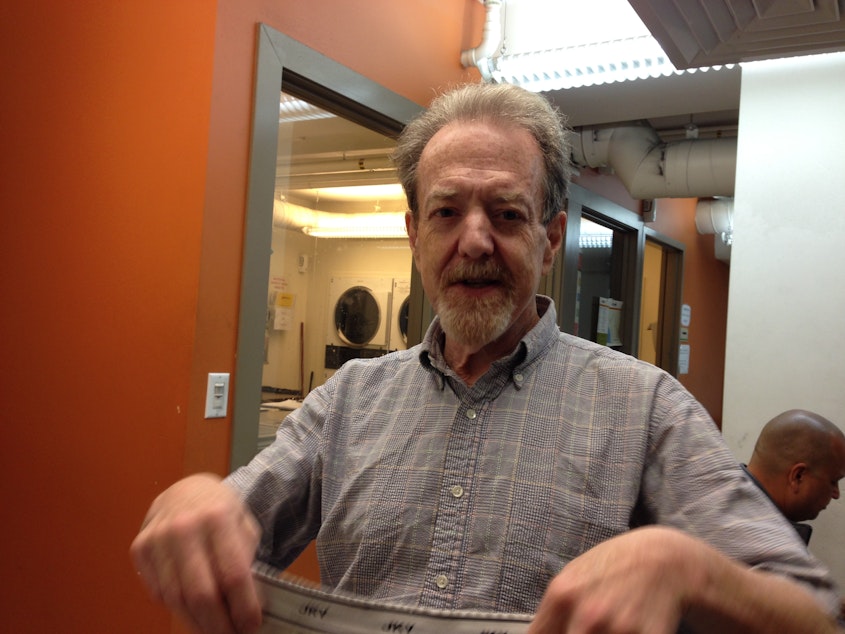

Baby boomers like Bill Totten, 61, who has been homeless since May. He went on disability in 2007; before his illness, he worked desk jobs for a phone company and the state.

He spends his nights at a shelter for homeless men over 50. Before that, he was renting a room in the basement of a house in disrepair: a crumbling foundation, no heat.

“I was paying $650 plus $100 for utilities,” says Totten. “And here’s the deal, the basement, it was an illegal subdivide.”

Seattle’s housing market is not only pricing renters out. It’s also causing people like Totten to live in substandard conditions because it’s what they can afford. Older adults may be vulnerable to offers of illegal housing. Some landlords have rented out garages as homes.

Sponsored

“We’ve seen that,” says Rory O’Sullivan, senior managing attorney for the Housing Justice Project. “We’ve seen sheds.”

The landlord rented out space beyond the house’s capacity. The building was unsafe on another level. One of the tenants assaulted him over an electric bill.

“I was tapped out. I was glad to have a place. I thought maybe it was an aberration at that one time, and then it happened again.”

Things got complicated. The landlord tried to evict him twice. The landlord wanted a new rental agreement. Totten withheld rent because the unit was in bad shape.

He said the situation wore him down. So he got out.

Sponsored

The Housing Justice Project helps low income people facing eviction. O’Sullivan says more tenants have been seeking help in the last four years, including people over age 60.

“This year the increase has been even more dramatic,” he says.

In previous years seniors made up about 13 percent of the legal clinic’s caseload. Now it’s closer to 20 percent. Other organizations that work with renters also report a spike in complaints.

O’Sullivan says in Seattle, landlords must give tenants two months’ notice if they’re going to raise the rent by more than 10 percent. And they can’t raise rents in buildings with code violations.

Tenants, especially older ones can protect themselves. First, by knowing their rights as early as possible. The lease is a good place to start. It spells out the obligations of landlords and renters when it comes to things like repairs, security deposit and maintenance.

Sponsored

“Try to document everything,” says O’Sullivan. “Make sure you get a receipt every time you pay rent. When you make a repair request, make sure it’s in writing and that you have a record of it. We see these issues everyday and the tenants who are able to negotiate a good outcome are the tenant who have read their lease and documented communications with their landlord.”

On a recent Wednesday morning, Totten checks in at the Hygiene Center in Seattle’s Pioneer Square. He hands his laundry card to the staff who asks if he wants to shower.

“No shower,” he says, “just laundry.”

Signed in, Totten puts his clothes on a scale to weigh them before they go in the washer. “Now we get to see if we made the magic 15 pounds. It’s like the county fair. I did! I’m three pounds under,” he says.

Totten spends his days walking. Or online looking for work to supplement his disability and Social Security checks. Some days he likes to take a break from it all.

Sponsored

“Once in a while I’d go to the main office of my bank, Wells Fargo, and, ‘Oh, Mr. Totten, how are you? Have a Dum Dum.’ Then I don’t feel like I’m walking around with an orange Harborview bag on 3rd Avenue.”

Totten has stored his belongings at a friend’s house while he looks for a permanent home. But the options for someone on social security are limited. He has about $1,700 a month to work with. He has more than rent to worry about.

“That has to keep my medical co-payments, my prescription co-payments, my bus pass and any incidentals.”

Totten says he might have to consider other cities like Everett or Tacoma, though he hears the average rents there are going up, too. And in his heart, Seattle is home.

“My city’s my family,” he says.