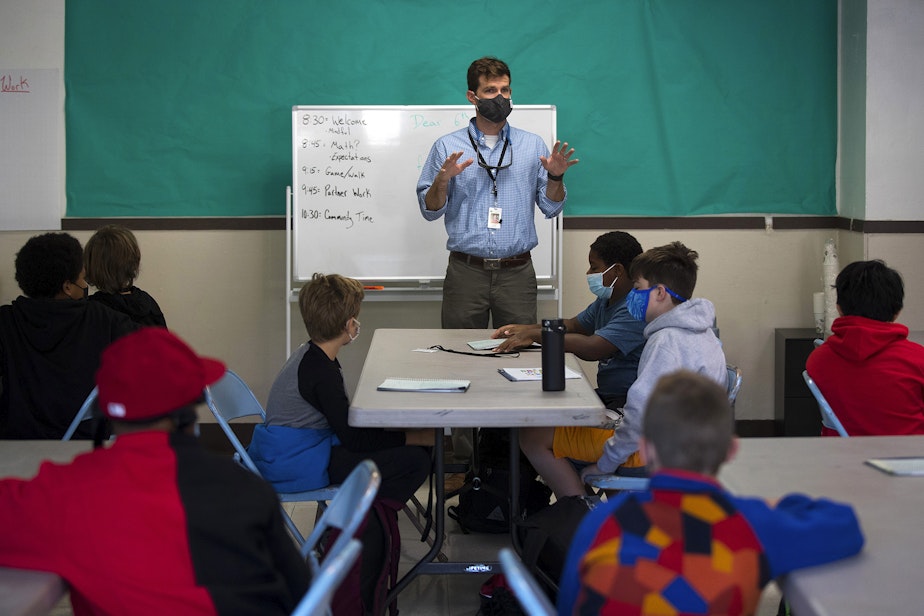

WA teacher turnover hits new high as students struggle to recover from pandemic disruptions

The number of teachers leaving Washington state classrooms has hit a nearly four-decade high.

The rate of Evergreen State educators leaving the profession climbed to nearly 9% between the end of the 2021-22 school year and the start of 2022-23, according to a new report published by the Policymakers Council at the education research center CALDER .

And the overall teacher turnover rate — which encompasses educators leaving the profession as well as those who switched schools or moved into a non-teaching role — stood at nearly 20%, the report found.

That’s the highest either rate has been in the 38 years Washington state law has mandated school districts report annual data on teachers and other school employees.

The Washington study, completed in collaboration with the University of Washington and the American Institutes for Research, is one of the first pieces of evidence to support longstanding national concerns about teacher shortages since the pandemic first upended education three years ago.

Other states are also starting to see similarly alarming teacher turnover rates. A recent Chalkbeat analysis of data from eight states, including Washington, found that more teachers than usual exited the classroom after last school year.

Sponsored

The exodus comes at a particularly inopportune time as schools across Washington and the nation scramble to help students recover from the unprecedented academic, social, and emotional tolls of Covid.

The study also reveals the state is disproportionately losing educators from high-poverty schools that serve students hit hardest by the pandemic and struggling the most to bounce back.

While teacher turnover rates have always been elevated in high-poverty schools, the study found the turnover gap widened during the third pandemic school year, from a roughly 2 percentage point difference after 2021 to a nearly 5 percentage point difference in 2022.

Pandemic or not, teacher turnover is detrimental to student learning almost anytime it occurs, said Dan Goldhaber, a co-author of the new study and a professor of social work at the University of Washington. Educator churn also causes the loss of connections in a school building, he said, including the relationships between teachers and students or their families, or those between fellow teachers or school staffers.

“When a new teacher comes into a school, even if that new teacher is as good as the teacher who departed, they do not have those kinds of relationships and knowledge of what’s going on in the school or what’s going on with the particular students,” he said.

Sponsored

To Jamillah Bomani, a teacher at Leschi Elementary in Seattle, those connections are critical.

As a fourth grade teacher in a neighborhood school, Bomani often teaches her former students’ siblings. Even if it’s several years later, Bomani already has a relationship built with that family and feels “a load is lifted” for both her and the family from the start of the school year.

“They’re often excited to go to the teacher that their sibling had and there’s already trust built there,” Bomani said. “It’s like, 'I know your name, I know your sibling, I know your mom and dad, so let’s get going — let’s do some learning. Let’s get right to it, because the relationship is already established.”

In the aftermath of Covid, Bomani has seen the damage resulting from increased teacher turnover. More educators and school staffers are coming and going and, in turn, families feel less connected to the school community, she said.

More than halfway through the school year, Bomani said her school is still struggling to fill an open special education teacher position. Not only does that harm relationships, Bomani said, but it also hurts the quality of education students are receiving, as teachers do their best to cover gaps while juggling a full workload.

Sponsored

“That means our interventions then are cut and our students aren’t getting those services,” Bomani said. “Not having the number of staff we need in a building has a bunch of different effects. It’s like dominoes: One thing falls, and … everything’s kind of out of whack.”

It also causes added stress for educators who are often already stretched too thin, Bomani said.

Teacher turnover aside, Bomani expressed fears about future educator layoffs in Seattle Public Schools, as the state’s largest district grapples with a $131 million budget deficit. Last week, Superintendent Brent Jones announced the district had notified at least 30 employees that their jobs may be eliminated in the coming months.

RELATED: Seattle Public Schools notifies employees of potential layoffs

As districts across Washington face similar budget woes, Goldhaber, the study co-author, suggested that raising teachers’ pay could be a solution to high turnover. But rather than increasing salaries across the board, Goldhaber said the state legislature should be more strategic by hiking entry-level pay for new teachers, in order to lure more people into the profession.

Sponsored

Goldhaber added that both the state and individual districts should also consider increasing pay in the subjects where staffing shortages are the worst — like special education and English as a second language — and at high-poverty schools that have a harder time recruiting educators.

“You need solutions to meet the nuance of the problem,” he said.