Hungry for knowledge of my culture, I head to my lola’s kitchen

We don't go to church for mass in my family. We go to my grandma's kitchen.

Food is my tie to my Filipino culture. But I don't know if my connection to food is enough for me to call myself Filipino.

I set out to use cooking as a way to dig deeper into my family's story and my own cultural identity.

The only words I know in Tagalog are busog, which means "full" and masarap, which loosely translates to "more delicious."

But outside of food, I don't know much about my family's roots. For a while, I couldn't even locate the Philippines on a map.

I wanted to learn more about my Filipino heritage, so I asked my mom and my grandma, my lola, to join me in the kitchen. They shared three of my favorite Filipino dishes, along with their stories.

Sponsored

Sinigang

My lola, Erlinda Conde, cooks sinigang, a deliciously sour soup with onions and tomatoes that bob as she stirs.

She grew up in a poor family in the Philippines. She got a college scholarship, studied chemistry and went to work for the NBI. (That's the FBI of the Philippines.)

When she learned about jobs in Chicago, she decided to immigrate. She had one suitcase and $240.

"Probably a good portion of my first year here," my grandma tells me, "I'm always crying."

She immigrated to Chicago in 1969. By 1980, the Filipino population in Chicago had almost quadrupled. But some people responded to the growing visibility of the Filipino community with racist attacks.

One time on a bus, two boys came up to her and stretched out their eyes, saying to her, "chinky, chinky."

Like sinigang, life in the United States was a sour experience at first for my lola, but she has no regrets. "Because it is here that I think we could have a good family," she said.

She found purpose in her work and with her husband and three daughters. One of those daughters is my mom, Teresa Engrav.

Sponsored

Adobo

My mom's dish is adobo. She calls it the "perfect combination." Adobo is meat marinated in a salty and sour mixture of soy sauce, garlic and vinegar, traditionally eaten with rice.

Sponsored

My mom grew up in a Filipino household in a vibrant Filipino community in Chicago. But when she left her house and neighborhood, she says it was "all about assimilating, and making sure we didn't have an accent."

My lola didn't teach my mom Tagalog, and when my mom tried to learn it from her cousins, she struggled.

"I'd speak, and I'd have a terrible accent," my mom said. "They would tease me, and the response would be, don't even bother."

Even so, my mom still identifies as Filipino. She says there are certain things that only Filipinos know about, like gestures and shorthand, which make her feel like a part of the community.

"You know, like they point with their lips, or a little bit of Tagalog mixed with English mixed with Tagalog and more English," she said.

Sponsored

Like many children of immigrants, my mom finds a way to preserve her heritage, but with a twist. Her favorite way to eat adobo is in a sandwich.

She tried to raise me with this idea in mind — stay true to your roots, but learn how to find your own voice.

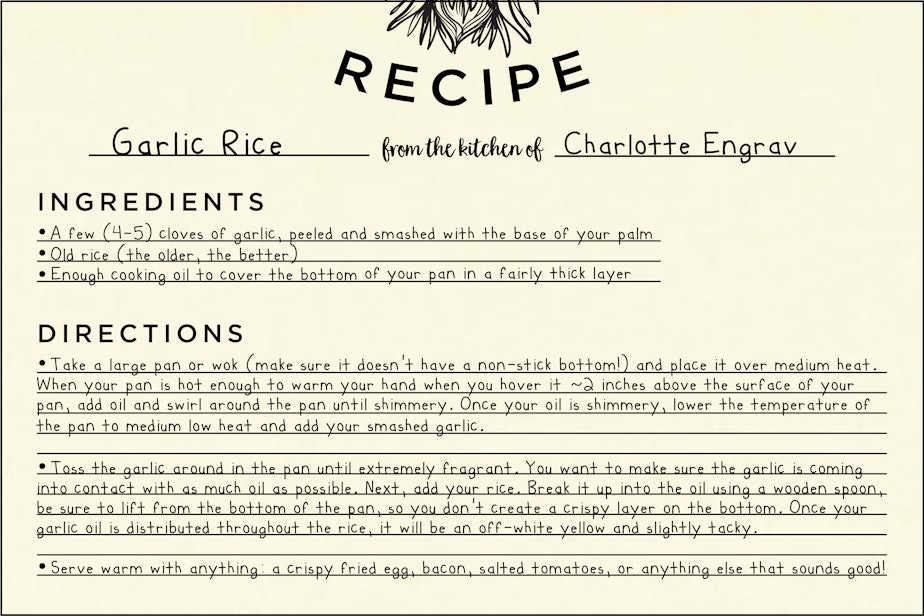

Sinangag

Now it's my turn. My favorite dish is sinangag — garlic fried rice.

I've grown up in a very Americanized home here in Seattle.

My mom put me in Tagalog school when I was younger, but it just didn't work out.

"You didn't love it," my mom recalled. "There wasn't a lot of reinforcement at home. It was just really easy to say, 'This is too much trouble.'"

It makes me sad. I wish the younger me would've appreciated what I was missing.

I'm grateful that I've been able to learn more about my family and my culture, but I've only scratched the surface.

I've started a Tagalog course online, and I want to learn how to cook more Filipino dishes.

I'm also working on perfecting my recipe for garlic rice. The secret? Dried out rice works best.

You need the old and the new.

So I combine old rice, like my family's history and my Filipino roots, with new, fresh garlic, like my Seattle upbringing.

I have a long way to go before I get to the perfect rice, just like I have a lot more exploring to do before I find my identity.

But I think I have all the ingredients.

This story was created in KUOW's RadioActive Intro to Journalism Workshop for 15- to 18-year-olds, with production support from Kelsey Kupferer. Edited by Ruby de Luna. Produced for web by Mary Heisey.

Find RadioActive on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and on the RadioActive podcast.

Support for KUOW's RadioActive comes from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Discovery Center.