How tweetstorms of misinformation skew our handle on the facts during a pandemic

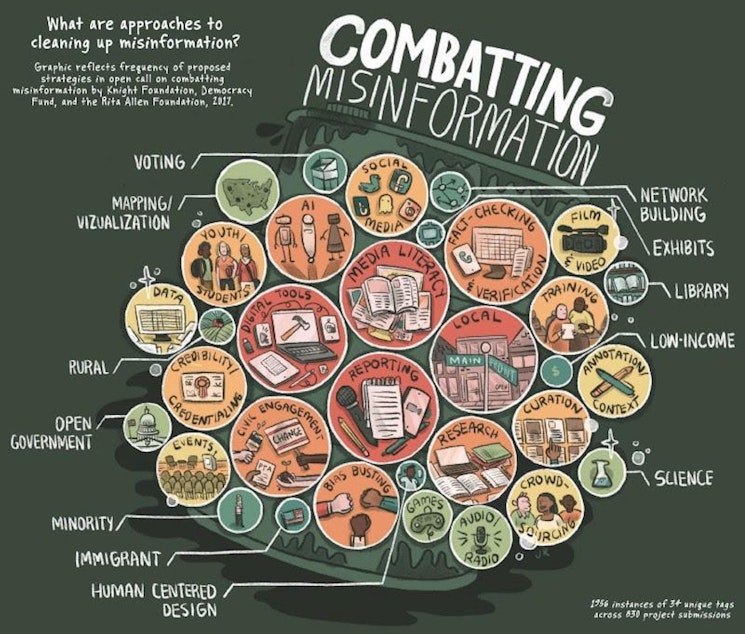

Before the pandemic hit, we were already living in a flood of misinformation, and conspiracy theories that circulate online. Now, the stakes are higher than ever.

A recent study found that nearly half the tweets sent since January about the coronavirus pandemic were likely sent by bots.

To make sense of what's happening right now, I'm joined by data scientist and head of the University of Washington's Center for an Informed Public, Jevin West.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Misinformation and disinformation have always been around, but during this global health crisis with 5 million infections so far, and when people need good information, it just feels like such a bad time for conspiracy theories to be circulating.

Jevin West: It depends on what perspective you're talking about. If you're a conspiracy theorist, it's the perfect time to be doing such a thing. The opportunity to send scam emails, to come up with crazy conclusions to almost disparate facts. This is a perfect time.

Even in science, which is something we track a lot, it's been difficult because science has been asked to move so quickly. Let me give you a specific example. One of the most shared papers on social media news of all time happened a couple months ago. It was published on bioRxiv, which is a pre-print archive.

RELATED: How the infodemic struck alongside pandemic

It claimed that there were common genome sequences in the coronavirus, as there are an HIV. Well, the paper was taken down, but not soon enough. It spread like wildfire. Now, why did it? Because it provided some solution to a potential bio weapon, or to all these other conspiracy theories around the coronavirus.

Sponsored

Even if science gets it wrong early on because it's trying to figure out all answers to this uncertain environment we live in, imagine how all the other conspiracy theories can flower.

It appears that this pandemic is actually driving misinformation. Why?

We're living in a time of extended uncertainty and that makes for lots of opportunities if you're a propagandist or an opportunist. If you want to sell something right now, this is a good time, because people want answers.

If you want to figure out whether you have coronavirus without having to go to the doctor and to a lab, well, I've got a solution for you. Everyone has an answer right now, because there aren't answers.

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon have found that nearly half of the Twitter accounts spreading messages about the coronavirus are most likely bots, and they're spreading conspiracy theories, like 5G wireless towers are actually causing coronavirus. What more can you tell us about that?

First of all, I will say that detecting bots is really difficult, but one thing we do know, we might not get the exact number of bots, but there are a lot of them out there. And the 5G wireless tower example is a really good illustration of how fast these things can spread.

Just to give you some specific numbers in our database about this conspiracy theory, back in April, when we started tracking this particular conspiracy theory more carefully, we had 5 million tweets just around the 5G. That was in a data set of about 500 million, all around Covid at that time, which was about one in every 100 was about the 5G conspiracy.

The 5G conspiracy theory has been around before Covid, but Covid gave it fertile ground to grow. It's grown so much that in some countries like the UK, people have climbed up these towers, broke them, or burned them. That's how serious they believe this.

Which takes us to the social media platforms. There have been hard questions for them in the past. I'm wondering now, as we're in this global health crisis, are they doing enough to police the content that makes discredited claims?

They're not doing enough, but I'll give them some credit for doing more than they have in the past. One of the things that they've been doing that's received a fair amount of attention, and for good reason, is that they've put up banners now. If I search coronavirus, or Covid-19, there'll be a banner that says "If you're searching for this, you should go check out the WHO or the CDC."

Sponsored

They're also doing a lot of post-specific fact checking. Individually videos or posts that are that are misleading and violate the rules that they've established for this. They're taking some things down, but I just don't think it's enough. We always want them doing more. I think they're trying, but I will say as a quick answer -- they're not doing enough, yet.

President Trump himself has shared false information about his administration’s response to the pandemic. For example, he Tweeted that the U.S. has done more tests than all countries in the world combined. He also said that the Obama administration left the cupboard bare, referring to the National Strategic Stockpile. Neither of those assertions are true. What do you see as the consequences of that?

I think the consequences go beyond just the current event we're in right now. If you do this too much, people start to lose trust, not only in that president, but also in the institutions in which we rely in a democracy. That's one of the worst collateral damages of this misinformation epidemic or "infodemic" that people are referring to, that it's this erosion of trust in the gatekeepers and people that are experts. If we don't have that it's hard to have a working democracy.

Let's say a family member of yours, or a close friend, is spreading misinformation online. What do you think is the best approach for them? How do you get them to stop?

One of the things that I do personally, is to establish a common concern. We're both concerned about the economy. We're both concerned about our health, and our family's health, but let's figure out where the most reliable information is on this.

Sponsored

We begin by sharing sources of news or data, or just simply "Where did they get those facts?" From there, you can start to establish what's more reliable, and what's not more reliable.

If you question or challenge someone else's source, though, wouldn't that make them defensive and start to shut the conversation down?

It can, and it does much of the time. I think sometimes you do have to establish that one source of data would be more reliable than another. We're always trying to be careful not to offend people, but I think it's important that there are certain sources that are more reliable. A government source, for example, is more reliable than a news site that no one has ever heard of.

What would be the number one thing you want people to know right now to inoculate themselves from this misinformation virus?

The number one thing is to include more in your information diet, those gatekeepers, more than you may have done in the past, instead of only relying, for example, on Twitter information, or only on Facebook, or only on your one news site that you go to. I think local reporting and local government officials are some of the best institutions right now that at least I personally trust. I think that's one of the things that I would do.

Listen to the interview by clicking the play button above.