Vitamin Treatment For Sepsis Fails In Large Trial

Hope for an effective and inexpensive treatment for the deadly condition sepsis has dimmed following results of a major new study.

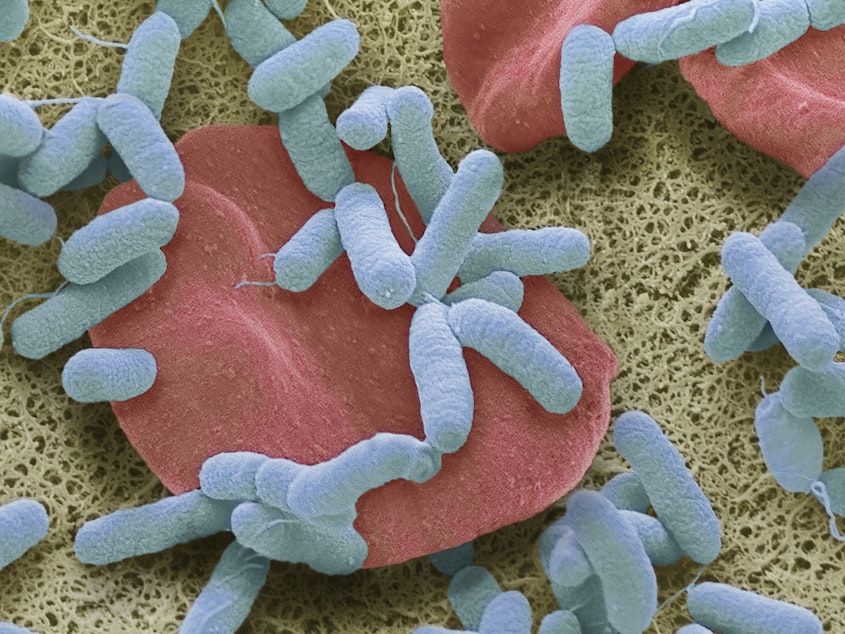

Researchers had hoped that a simple treatment involving infusions of vitamin C, vitamin B1 and steroids would work against a disease that kills an estimated 270,000 people each year in the United States and 11 million globally. Sepsis, or blood poisoning, occurs when the body overreacts to infection. It leads to leaky blood vessels, which can cause multiple organ failure.

Excitement about this treatment took off in early 2017, when a well-regarded physician and researcher in Norfolk, Va., Dr. Paul Marik, reported that he had remarkable results treating his sepsis patients using this combination of agents. Some doctors in intensive care units started using the method immediately, based on those early results. Many others said they wanted to wait for results of a more carefully controlled study

The largest scientific study published to date has now reported its findings. It finds no benefit at all from the "Marik cocktail." It involved more than 200 patients in Australia, New Zealand and Brazil. Results were presented Friday at a meeting in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and were published online Friday in JAMA, the journal of the American Medical Association.

Dr. Rinaldo Bellomo, at Austin Hospital and Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, led the research team. He decided to study the treatment because sepsis takes such a large toll — it's a leading cause of death in hospitals — and treatment options are limited. There's no effective drug, though aggressive use of antibiotics and careful care in the ICU can help.

Sponsored

"People latch on to promising interventions because of that frustration," he tells NPR. "And it's understandable. But, you know, the view from here is that we shouldn't substitute hope for evidence."

His evidence does not support those who believe the vitamin C treatment is effective.

"It is discouraging," says Dr. Craig Coopersmith, interim director of the Emory Critical Care Center at Emory University. "Right now, sepsis is the number three cause of death in the United States and the number one or two cause of death in the world."

Coopersmith says the results don't slam the door on the treatment entirely — there's still some chance that it has a modest effect on overall survival, he says, but the study didn't involve enough patients to answer that question. The study found no effect on short-term survival or improvement in certain clinical markers of disease.

"I don't think we can yet say that there is no impact," Coopersmith says. "I think we could say that the jury's still out on that."

Sponsored

He assumes that doctors who are inclined toward using the treatment will continue to do so, at least for now, while those who adopted a wait-and-see approach are sticking with that.

Indeed, Marik, who remains a strong proponent of this approach, rejects the findings of the study. He tells NPR that by his reckoning, patients in the study received treatment far too late in the course of their disease. "It's like giving it to a patient who's dead," he says. "It's of no benefit. The horse was out of the barn miles beforehand."

Marik, at Eastern Virginia Medical School, gives his patients the vitamin C infusion as quickly as he recognizes signs of sepsis. That's impossible to do in a study in which participants must be enrolled in a study and then randomized into one of the two comparison groups before treatment can begin.

"The question is, why does this study not replicate real-life experience and the experience of hundreds of clinicians around the world?" he asks.

Marik says in his experience, the treatment is only effective if given within six hours after someone has suspected sepsis. At the meeting in Belfast, Dr. Tomoko Fujii, on the study research team at Monash University, said they provided treatment an average of 12 hours after patients arrived in the intensive care unit. Patients came from a variety of locations, including the emergency room, and she said they have no information about how long they had been septic before arriving at the ICU.

Sponsored

Coopersmith is part of a larger study — involving 501 patients — that has also put the vitamin C protocol to the test. That research group has completed collecting data and is now in the process of analyzing the results and preparing a publication. A second group, coordinated out of Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, also studied the protocol among a group of about 200 patients.

Findings from those studies should help doctors and researchers come to a more definitive conclusion, says Bellomo in Australia. "I think that will be really good, because we would have a much larger body of evidence. I hope by the end of 2020 to provide more nuanced and more detailed views of what happens with this kind of intervention."

You can contact NPR Science Correspondent Richard Harris at rharris@npr.org. [Copyright 2020 NPR]