What Don't You Talk About With Your Mom?

The most immediately useful question I think I can answer about What My Mother and I Don't Talk About is whether you should buy it for your mother for Mother's Day.

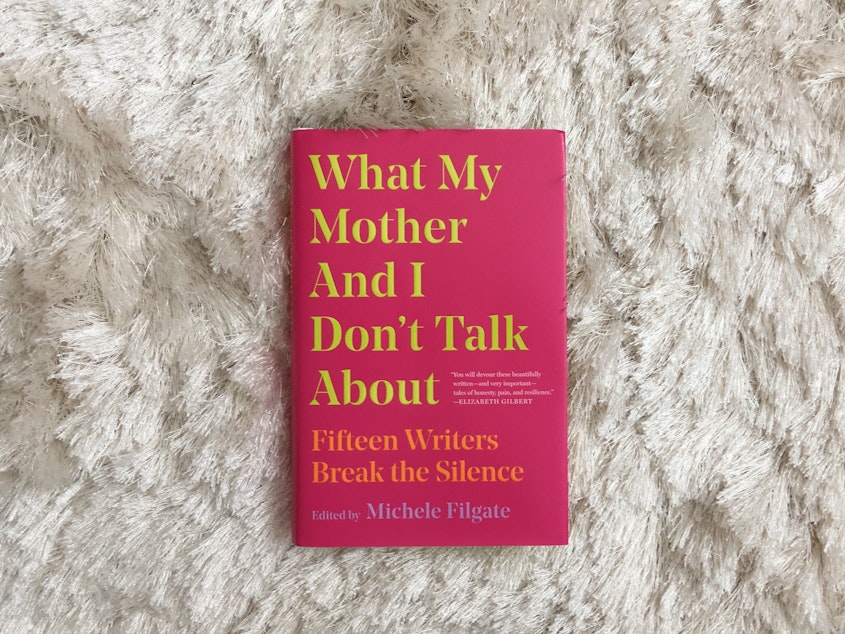

After all, it will hit your local bookstore's display at the start of May, just the time of year when you smack your forehead and go, "Ah, shoot, right, Mother's Day." And it seems designed to be eminently giftable — attractively neon colored, not intimidatingly thick, broken into 15 read-in-a-sitting essays.

So my best answer to the question of whether you should gift this to your mom is, "Sure, if you don't mind having some uncomfortable conversations."

That's not an insult, by any means. It's more a caution to the unsuspecting reader who might think a title like What My Mother and I Don't Talk About promises tales of tough topics broached, conversations had, relationships restored and hugs all around while the violins swell.

Chicken Soup for the Soul this ain't. There's a lot of pain in this book — ranging from the simple yearning to know Mom better to the trauma of abuse and addiction — and the tales come from a diverse, accomplished array of writers.

Sponsored

Nevertheless, in the interest of summarizing, there are four main topics that these writers aren't talking about with their mothers: terrible things their moms endured, terrible things the writers endured, what their moms were like before they were moms and the ways their moms failed to be good moms.

Among these essays, there are some true standouts, like Carmen Maria Machado's matter-of-fact explanation of why she and her mother no longer talk and how it weighs on her own decision about having children. Another is Nayomi Munaweera's journey of figuring out that her mother has a mental illness. Or Dylan Landis' maddening, decades-spanning curiosity about whether her mother — pre-motherhood — had a relationship with a painter she occasionally talks about.

But then, this is a collection of essays. And the question is why they should be bundled together and read as a unit, rather than as articles randomly encountered in magazines or online.

Part of the answer is the questions that these essays together raise. Chief among them: What makes the mother-child bond so unique that it should get a full book?

As a friend asked me when I told him about this book: "What about a book called What My Father and I Don't Talk About?"

Sponsored

"I think the answer to that for most people is 'everything,' " I responded.

I was joking — but not quite. We heap loads of expectations onto parents, but for mothers more than fathers — at least, in contemporary American society — many of those expectations center on comfort and emotional attachment.

And so this book is about people seeking that comfort and attachment. It's an accounting of the wide variety of roadblocks that get in the way of that bond that we are told, via Hallmark movies and schlocky songs and cutesy cross-stitchings, is sacred and therefore effortless.

The writers in this book do not necessarily find that bond sacred, and they certainly don't find it effortless. And while some eventually do connect better with Mom, some just don't, and they write affectingly about coming to terms with that. Reading the book is to take the sacred mother-child ideal down from its pedestal and inspect it, dissect it, run tests on it, muck it up a bit.

At its broadest level, this book is about the soul-rattling realization that despite often having the astronomically best of intentions, our mothers still mess up — sometimes in life-altering ways. It's about how, despite our love or desperate need for them, we mess things up too. And it's also about the gut punch that happens when some children are forced to legitimately wonder just how good their mothers' intentions ever were.

Sponsored

But then, it's about how much more livable those relationships might be if someone just said those three magical words.

Those words are not "I love you" but, rather, "Are you OK?" Or, even more difficult: "Hey — I'm hurting."

As it turns out, in a relationship where love is so often implied, so much else still needs saying. [Copyright 2019 NPR]